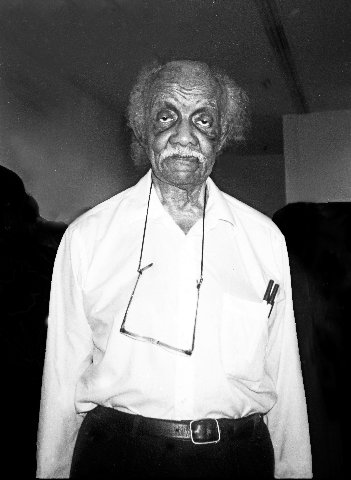

Words and Images Allan Rohan Crite 1910 – 2007

A Virtual Visit to St. Botolph Club Exhibition

By: Charles Giuliano - Apr 08, 2020

Words & Images Allan Rohan Crite 1910 – 2007

Co-Curators Jean Gibran - Cathryn Griffith

March 4 - April 17, 2020

St. Botolph Club

199 Commonwealth Avenue

You Tube Link https://youtu.be/VRyIEHjFW60

On many levels, the exhibition Words & Images Allan Rohan Crite 1910 – 2007, co-curated by Jean Gibran and Cathryn Griffith for Boston’s St. Botolph Club, was among the most anticipated and unique of the 2020 season.

Because of the range and quality of work it is a museum level exhibition. As co-curator Jean Gibran, widow of the artist Kahlil Gibran, told me she was pleased to secure loans including from the Boston Athenaeum which owns major examples of the work.

There were a number of elitist social clubs founded in the 19th century. Among them, in what was formerly a private mansion on Commonwealth Avenue, is St. Botolph Club founded in 1880. It is unique for its orientation to the arts. This project is one of many celebrating Boston artists many of whom have been members of the club.

Mounted in a private club, with public access limited to one afternoon, the show was never intended to be widely seen and promoted. That became even more so when as non-essential the club has suspended access because of the current pandemic. That occurred just a week after the opening.

The exhibition may be experienced through a video tour linked to You Tube.

We are members of the National Arts Club in New York which shares privileges with St. Botolph. During a stay in Boston last fall we enjoyed dinner with a friend. By serendipity that night there was a gathering of individuals involved with the Crite project.

I met his widow, Jackie Cox-Crite, who is committed to promoting the work. We spoke at some length about projects and have connected since by e mail. She declines to offer an update as the pandemic is disrupting plans for projects over the next several years.

It is widely considered that Crite was a major Boston artist of his generation. His remarkable life and career widens defining art in Boston from the depression years through the post war era.

That’s when the hegemony of the fine arts shifted from genteel forms of American Impressionism to roiling Boston Expressionism. Because these artists were primarily Eastern European Jewish immigrants and their descendants it’s precisely when, for the most part, the Museum of Fine Arts lost interest in living Boston artists.

The MFA exhibited work by Hyman Bloom in a 1959 group show. Some 40 years lapsed until Erica E. Hirshler curated the magnificent Hyman Bloom Matters of Life and Death. It was presented with a scholarly catalogue. The exhibition was glowingly covered by national media.

Isn’t it right and just for the MFA to offer fair and equal treatment to Crite? He is on the short list of most accomplished Boston artists. That question is all the timelier as the museum has recently been targeted with accusations of racism.

The museum’s director, Matthew Teitelbaum, came to the MFA from the Art Gallery of Ontario, in his native Toronto. As we observed during a fall visit to the museum, on his watch, the museum took great strides to collect and display historic and contemporary art of First Nations. This is true for all Canadian museums.

Since 1969, Edmund Barry Gaither has been director and curator of the Museum of the National Center of African American Artists. In 1970 he curated for the MFA Afro-American Artists New York and Boston. As an adjunct he organized eight exhibitions for the MFA. In 2008 Gaither curated In Memory of Allan Rohan Crite for Museum of the National Center of Afro-American Artists.

In 2011 the MFA acquired 67 works by key African American artists from the collector John Axelrod. Since 1985 he has donated a range of 700 works to the museum.

The MFA owns and displays work by Crite but not commensurate to his status. There are no indications of plans for a retrospective or acquisitions. Because of the recent instance of racism school children were invited to curate a show that includes Crite drawings in the rotunda. He is also represented in a current special exhibition of self portraits. The museum, however, is closed because of the pandemic.

The student curated show Black Histories: Black Futures features works by well-known artists including Archibald Motley, Norman Lewis, James Van Der Zee and Dawoud Bey, in addition to highlighting painters with connections to Boston, such as Loïs Mailou Jones and Allan Rohan Crite. It also brings fresh attention to rarely shown works by artists such as Eldzier Cortor, Maria Auxiliadora de Silva and Richard Yarde.

Because the MFA is noted for missing the boat on modern and contemporary art it has many gaps to fill with limited resources to do so. A crucial strategy for building a collection is to exert leadership through exhibitions in areas of interest. If you build it they will come.

It is ironic that Teitelbaum has long been aware of Crite and his significance. Recently, I posted a 1993 interview when he was ending a role as acting director of the Institute of Contemporary Art.

We were discussing the ICA’s Malcom X exhibition. It was inspired by the early years of Malcolm Little in Boston. Teitelbaum was weighing the issue of conflating past and present in a museum dedicated to contemporary art.

“Why do I want to put Allan Crite’s work from fifty or sixty years ago in the ICA? Answers to questions about why without being locked into the specific questions of what” Teitelbum told me.

What follows is an excerpt of text from the St. Botolph catalogue.

Hailed as the “Dean” or “Granddaddy” of African-American artists in New England, Allan Rohan Crite is less recognized as “Child Prodigy.” Born in North Plainfield, New Jersey, he, his engineer father, Oscar William Crite, and poet mother, Annamae Palmer Crite, moved to Boston in 1910, his birth year. Eventually, the close-knit family settled in the mostly African-American community of Lower Roxbury where they purchased a building. Number 2 Dilworth Street (no longer standing) became the artist’s beloved home –studio- sanctuary for nearly five decades.

The only child spent hours sketching while his mother wrote. Visits to historic sites and museums led to his observations and portrayals of local people and places.

By nine, his precocious drawings were recognized at the newly opened Children’s Art Centre on Rutland Street, part of the South End Settlement Movement. Attending Boston English High and Vocational Art Classes at School of Museum of Fine Arts, he began to receive notice.

Several of his “action figures” appeared in the 1925 edition of The Art of Seeing by artist/educator Charles Herbert Woodbury and Elizabeth Ward Perkins, then President of the Art Centre. Two years later, the New York monthly Opportunity, A Journal of Negro Life reproduced his “Bull Fight” an imaginative sketch that drew “comment and special commendation.”

In 1929, the nineteen-year-old Museum School scholarship student exhibited at the Boston Society of Independent Artists. Within three years, his painting, “Settling the World’s Problems” was celebrated in the Society’s annual exhibition and received a Boston Transcript rave review. From then on, with a focus on academic and church roots, Allan Rohan Crite’s complex and various careers moved rapidly.

His legendary “Neighborhood Series” of oil paintings from the Great Depression throughout World War II and involvement in the Federal Art Project of the Works Projects Administration prepared him as a long-time illustrator for the Boston/Charlestown Navy Yard. Crite exhibited nationally and created murals, spiritual books, and Bulletins honoring his Episcopalian Faith. Awards abounded, including the naming of Allan Rohan Crite Square (or “Triangle” as he once suggested) next to his home, 410 Columbus Avenue, where he enjoyed sidewalk chats with neighbors.

Interview between Berkshire Fine Arts publisher, Charles Giuliano, and gallerist Arthur Dion of Gallery Naga. Posted March 25, 2020.

Charles Giuliano Let’s talk about an artist in particular, Allan Rohan Crite (March 20, 1910 – September 6, 2007). He was one of the first African-Americans to graduate from the Museum School. You opted to represent him when he was then quite elderly. You felt that he was an important historical figure.

Arthur Dion He is.

CG I was present during a NAGA exhibition of his work on a day when MFA curator Cheryl Brutvan visited. She was in the gallery on other business and approached you at the counter. We have different characterizations of how she did or did not interact with the work on view.

AD She glanced at it.

CG I didn’t feel that it was my place to comment on her obvious snub of the work. I was just there to observe. That behavior seemed to represent everything that was wrong with the MFA, particularly Malcolm Rogers, who she worked for and who endorsed her attitude.

AD We can pick on Cheryl, but this is a racist art scene. And a pretty racist city. But I’m not picking on Boston. You can say that about any comparable city in the country. There are skilled, wonderful, interesting, charming Black artists in this town - and there always have been - who can’t break into the fundamentally white art scene.

Allan Crite is shown at the MFA now because a series of cultural and political circumstances have changed. But that doesn’t change the fact that, at that time, most of us couldn’t see past our blinders. I had practically no success presenting Allan’s work, aside from some wonderful purchases of my own. What you don’t know is that my engagement with Allan far predates my engagement with NAGA.

At the School One Gallery, we started to do more ambitious things. One day Leonard Smith, who was teaching painting, said, “You have to come with me tonight to the Rhode Island Black Historical Society to see a presentation by this painter, Allan Crite. You’re going to love it.”

Allan showed images of his work, and I was knocked out. He said, “If any of you would like to visit me in Boston, you may.” After the talk I told him I wanted to take him up on that. This was probably 1980. Allan was not that old at that point. He was younger than we are now, but not that old. His house in the South End was a museum. He was completely charming, with refined and shy manners. He was sweetly and tartly funny. His work was ambitious and, in many ways, courageous.

I said, “I want to show your work.” At the school in Rhode Island we staged the largest exhibition of his work that had been mounted to date. There were 51 objects, including ecclesiastical pieces, altarpieces, illustrated spirituals, family portraits.

I invited Barry Gaither to give a talk at the opening. We got coverage in the Boston and Providence papers. Robert Taylor (Globe) did a photo and mention of the show. So, for a scruffy little alternative high school, we thought this was pretty terrific. I was a big fan, and I still am. I was friendly with Allan throughout his later life in many ways.

For at least the last 20 years of his life he was seen as the patriarch of Black artists in Boston. As far as I could tell, every Black artist in town knew and revered him. His life describes the stations of the cross of being a Black artist in Boston and America. He was seen and unseen, respected and disrespected. He was valued and devalued. From my point of view, he has still not been satisfactorily recognized. And aside from all that jazz, he was really good.

Selected Events Timeline

1910 Born North Plainfield, New Jersey ~ March 20 ~ Moves to Boston with parents

1915 Enrolls Boston Public Schools ~ First ~ Lafayette ~ then Bancroft-Rice

1918 Attends Children’s Art Centre ~ 36 Rutland St. ~ South End, Boston

1924 Attends Boston English High ~ Art Class, School of the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston

1926 Second Prize in Back Bay Boston drawing exhibition for “people of all ages”

1928 Works at New Hampshire estate of artist Jane Kilham & architect Walter Kilham

1929 Father Oscar William Crite incapacitated by stroke

1929-1956 Exhibits Boston Society of Independent Artists

1930s Attends courses Massachusetts College of Art ~ Boston University

1931 “Depth” illustration reproduced ~ May issue ~ Opportunity: A Journal of Negro Life

1934-1936 Receives Boit Prize ~ Graduates School of the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston

Museum of Modern Art, NY ~ Corcoran Gallery of Art, Washington D.C.

1937 Father Oscar William Crite dies

1940 35 Under 35 ~ Museum of Modern Art, NY

Begins at Boston Naval Shipyard as engineering draftsman

1941 American Negro Art: 19th and 20th Centuries ~ Downtown Gallery, NY

1949 Works with Rambusch Decorating Company on ecclesiastical murals

1950s Lectures on liturgical art ~ Episcopal Seminaries throughout Nation

Executes tooled metal Altars ~ Stations of the Cross ~ Textile Church Banners

1955 Purchases Multilith 1250 offset press ~ Prints weekly Church Bulletins, etc.

1965 Visits Ecumenical Centers during three-week European tour

1966 Travels to Puerto Rico for Migrant Workers Program

1968 Receives Bachelor’s Degree from Harvard Extension School

Annamae And Allan R. Crite Prize established Harvard Extension School

1969 Visits Mexico ~ Publishes Multilith sets of Stations of Cross folios

1971 Moves with mother Annamae Palmer Crite ~ 410 Columbus Avenue, South End

Organizes The Boston Collective with African-American artists

1975 Begins as Grossman Librarian ~ Harvard Extension School

Jubilee: Afro-American Artists ~ Museum of Fine Arts, Boston

1977 Mother Annamae Palmer Crite dies

1978-2004 Honorary Doctorates ~ Suffolk University ~ Emmanuel College ~ Mass. College of Art General Theological Seminary ~ Virginia Theological Seminary

1982 Lost and Found Paintings Allan Rohan Crite ~ Museum of Afro-American History

1983 Travels to China & Japan with 12 Boston Collective Artists

350th Annual Harvard University Medal ~ Harvard University

1986 Boston Collective Art Exchange ~ China ~ Exhibits ~ Guangdong Fine Arts College

1991 Allan Rohan Crite Square named ~ Columbus Avenue & West Canton Street

1992 Men of Vision Award ~ Museum of African-American History

1993 Marries Jacquelyn Cleveland Cox ~ Known as Jackie Cox-Crite

1994 Certificate of Appreciation ~ St. Bartholomew’s Episcopal Church, Cambridge

1997 Allan Crite’s Boston ~ Boston Athenaeum

2001 Allan Rohan Crite Artist - Reporter ~ Frye Museum, Seattle

2007 Dies peacefully ~ Memorial Service Boston’s Trinity Church

2008 In Memory of Allan Rohan Crite ~ Museum of the National Center of Afro-American Artists

Publications by the artist

“PEOPLE,” Boston: Self Published, during “Artists in Residence,” Museum of Afro-American History. 1977.

Crite, A. R., “The Great Vigil of Easter: A Commentary, Virginia: The Parishes of The Episcopal Church,” 1977.

Crite, A. R., “A Journal of Community Leaders’ Tour to China,” 9-25 November 1983, Self Published.

Crite, A. R., “The Revelations of St John the Divine,” New York, The Limited Editions Club, 1995.