Michael Feinstein Great American Songbook Initiative

Archive at Center for the Performing Arts Carmel, Indiana

By: Charles Giuliano - Apr 10, 2013

The first long playing albums LPs were introduced in 1948. The prevailing form of recorded music remained the 78 rpm shellac disc. This dictated that the dominant form of popular music of the Great American Songbook was the single or three minute song.

When initially introduced, 12-inch LPs played for a maximum of 45 minutes, divided over two sides. In 1952, Columbia Records produced extended-play LPs that ran for as long as 52 minutes, or 26 minutes per side. These featured original cast albums of some Broadway musicals, such as Kiss Me, Kate and My Fair Lady. The 52+ minute playing time remained rare because of mastering limitations. Most LPs continued to be issued with a 30- to 45-minute playing time.

Cheaper 10” LPs were used for popular music while the more expensive 12” discs were confined to releases of classical music and Broadway shows. The potential to capture live jazz performances and jam sessions started in 1956. George Avakian of Columbia Records set up equipment during the 1956 Newport Jazz Festival which resulted in Duke Ellington’s game changing “Diminuendo in Blue.” It featured the extended solo of tenor sax player Paul Gonzalvez which took up one side of the album.

As a youngster Mom regularly took us to New York to see Broadway shows; South Pacific, Annie Get Your Gun, Brigadoon, Guys and Dolls, Finian’s Rainbow. We saw the final performance of the touring company of Oklahoma at the magnificent Boston Opera House on Huntington Avenue just down from Symphony Hall. It was sacrificed to the expansion of Northeastern University.

It amazed me that Mary Martin actually took a shower on stage while singing “I’m Gonnah Wash That Man Right Out of My Hair.” I wore the grooves out of the original cast recording while mastering a parody of Ezio Pinza’s “Some Enchanted Evening.”

As Michael Feinstein observes during an episode of season three of his Great American Songbook on PBS, prior to the LP and original cast recordings in the 1950s, there is scant archival evidence of the epic era of Broadway musicals, big bands, tin pan alley, and popular songs.

Other than costumes nothing was saved when shows closed. Sheet music and scripts were routinely trashed. Only rarely has any filmed footage of great performances survived.

Feinstein and a handful of others have collected these priceless ephemera. Heirs of estates of musicians, composers and arrangers have faced the problem of what to do with the material filling boxes in garages and attics.

This was the inspiration behind the Michael Feinstein Great American Songbook Initiative. It was established at the Performing Arts Center in Carmel, Indiana with a $1 million gift from Michael Feinstein and his spouse Terrence Flannery. There is a current drive to match that with another $1 million.

During a recent visit to Carmel we enjoyed a performance of Feinstein with Barbara Cook. That was followed by an interview.

The eventual goal is to create a separate building to house a museum, archive and library. To provide for the art form a facility like the The Rock and Roll Hall of Fame in Cleveland and Nashville’s Country Music Hall of Fame. In its current form the program in Carmel resembles The Institute of Jazz Studies at Rutgers University in New Jersey. Another resource for this material is the Library of Congress and Smithsonian in Washington, D.C.

Why Carmel, Indiana we asked during a tour of the archive and its limited special exhibition area?

It seems that Feinstein did not want to locate the collection in a major urban setting. In that sense the superb facility which opened in Carmel in 2011 becomes a unique destination for his programming as artistic director as well as a magnet for scholars and fans of the music.

The visiting American Theatre Critics Association was given a behind the scenes tour led by archivist Lisa Lobdell. It was immediately evident that the collection will soon outgrow its current space.

During frequent visits to Carmel Feinstein regularly arrives with shopping bags of priceless stuff from his collection. In the PBS series he described purchasing a pair of Fred Astaire’s shoes in a silent auction. He was the only bidder. Friends asked if he had tried them on? That never occurred to him. But they are a perfect fit at size 8 D.

Having those magic slippers, however, has not turned him into a dancer. During a PBS scene of him taking ballroom instructions it is evident that, while a great singer, he’s no hoofer.

I can totally identify with his mania for collecting. My uncle ran a record shop Freddy’s Music Unlimited in Newton Corner, Mass. On weekends I would help out in the store. We would stop at the distributor before opening the shop. It was a time when customers would play the music before they bought it. So I heard a lot of the records.

Local music stores, with their listening booths, stocked 78s, 10” and 12” LPs and 45s. You could spend all afternoon listening to music and then purchase one LP so they don’t kick you out next time.

Those stores got stuck with inventory and many went out of business when, just after Christmas, the record companies stopped issuing 78s. That and downtown discounters like Sam Goody’s killed the local record stores.

When my uncle passed away I inherited his collection which since then has grown to some 7,500 LPs. I have an ongoing project to transfer them to the hard drive and I Tunes. Which allows for cutting CDs to listen to on the road and share with friends.

Don’t ask about the years of lugging the collection from apartment to apartment.

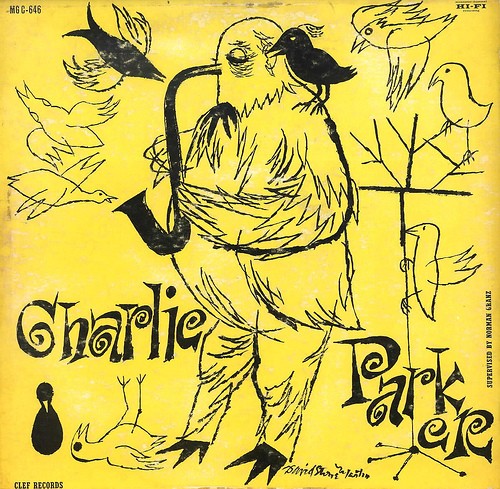

Some of the LPs from the 1950s are as much prized for their graphics as for the discs which are often worn out from being played so much on primitive equipment. In particular I am a fan of the jazz illustrator David Stone Martin.

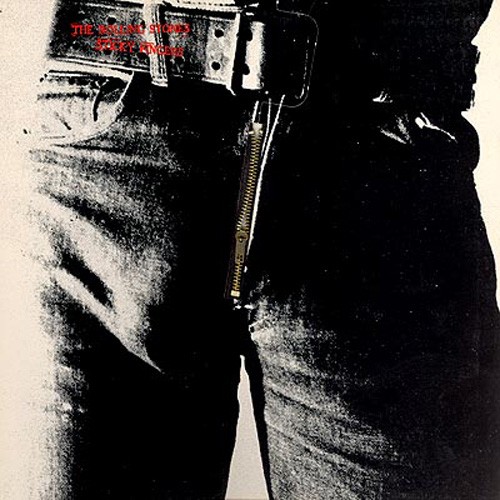

I treasure the later picture discs, colored vinyl, and a Talking Heads album designed by Robert Rauschenberg. I have never played it. Or the Sticky Fingers LP by the Stones with the real zipper in Mick’s shorts designed by Andy Warhol. I have a couple of white test pressing albums which Captain Beefheart hand decorated for me while driving around NY in the back seat of a limo. And about a dozen sealed copies of Great White Wonder the first bootleg of Bob Dylan.

Collectors are weird.

Like the time I interviewed Tiny Tim at Boston’s Playboy Club. I asked how he found those tunes like “Tip Toe Through the Tulips?”

“Oh, Mr. Giuliano” he said in a fluttering gush “I just love to collect 78s. Some of them I put my face next to and smell the labels.”

My great aunt Catherine, a reader of the Boston Herald, loved that interview. Whenever we got together for a holiday she asked me to tell her more about Tiny Tim.

Surely his archives belong in Carmel.

We learned by talking with Feinstein and the archivist that, while there was an obviously classic era for the Great American Songbook there is no fixed end to the timeline. Some would argue that it starts in the 19th century with Stephen Foster and the songs of the minstrel shows through decades that elided into Vaudeville and eventually Broadway.

Material continues to be added to The Great American Songbook and enduring the test of time will take their place among standards.

The true test is not the longevity of the material but the young artists who interpret the canon and keep it alive. In that regard Feinstein is a one man band and advocate.

Toward that end The Great American Songbook High School Vocal Academy & Competition has been established. Applications for this year’s competition closed on April 5.

Regional finalists for the 2013 competition will be selected from eligible states: Alabama, California, Connecticut, Florida, Georgia, Illinois, Indiana, Iowa, Kentucky, Maine, Massachusetts, Michigan, Minnesota, Missouri, Nevada, New Hampshire, New York, North Carolina, Ohio, Rhode Island, South Carolina, and Wisconsin.

Judges select students for regional competitions held in five cities across the country. The regional competitions, held April 2013 - June 2013, include a full day of workshops followed by an evening performance. Two finalists will be selected in each region.

The ten regional finalists are invited to the Feinstein Initiative’s headquarters in Carmel, July 21-26, 2013, to participate in a five-day “boot-camp” on interpreting and performing the music of the Great American Songbook. The final competition performance will be held in the 1,600 seat Palladium Concert Hall at the Center for the Performing Arts.

In addition to $3,000 the first place winner serves as the Great American Songbook Youth Ambassador for one year with opportunities to perform. Second place receives $2,000 and third place receives $1,500.

Some 112 boxes of material arrived at the archive last year. In a relatively short time to date the archive includes: 37,000 pieces of sheet music, 5,000 LPs, 4,000 books, 700 photos, 500 lacquer discs, 200 aluminum discs, 2 pianos and 1 beach towel.

There is method to the mania.

“It is one of our goals to raise money to build a free standing museum” stated the progressive Mayor of Carmel, Jim Brainard. “The nature of this collection which has national significance allows us to ask for funding, not just in Indiana, but across the U.S. A larger museum will attract more visitors to Carmel and provide benefit to many Carmel businesses from those that visit from other states.”

Lobdell said that “We have acquired 101 discrete collections. Our largest to date, 276 boxes, belonged to the San Francisco collector Bob Grimes and consists of 34,000 pieces of sheet music and 3,000 books plus a host of other items.”

We asked if she had particular favorites among the thousands of items.

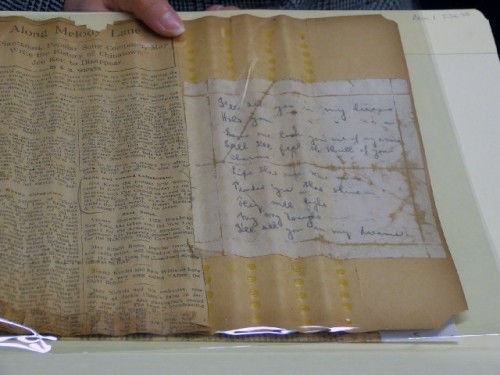

She showed us a scrap book containing the proverbial lyrics written on a cocktail napkin. "I'll See You in My Dreams" was written by Isham Jones, with lyrics by Gus Kahn. The song was published in 1924.

Wow.

Below are descriptions of the three episodes of Season 3 of Feinstein’s Great American Songbook currently airing on PBS.

Episode 1 of Season 3: Show Tunes

Stars in the Broadway universe don’t shine much brighter than Stephen Sondheim, Angela Lansbury and Christine Ebersole, all of whom appear in this episode about great American musicals. Sondheim reveals the composers he most admires and shows Feinstein some rare home movie footage of the original Broadway production of the classic Follies. Tony Award-winner Ebersole gives a tour de force performance of a showstopper from the stage musical Funny Girl, and Lansbury reflects on her Broadway career, from Mame to Sweeney Todd and Gypsy. (Michael also has a surprise for Angela.) Feinstein discusses his personal relationship with the lyricist Ira Gershwin and performs the classics “Lullaby of Broadway,” “Let Me Entertain You” and “No One Is Alone.”

Episode 2 of Season 3: Let’s Dance

Fred Astaire is Michael Feinstein’s favorite singer—but he also was the favorite singer of Irving Berlin, Cole Porter and the Gershwins. Why was this dancer, first-and-foremost, so beloved by the America’s great composers? With that question Feinstein launches into an exploration of the marriage between music and choreography, unearthing rare home movies of Astaire rehearsing on set, and some remarkable memorabilia from that other screen-dance icon, Gene Kelly. Kelly stuns in never-before-seen footage of his Broadway debut in the original Pal Joey. Liza Minnelli struts her stuff in two rare vintage clips—including a duet with Gene Kelly. Feinstein indulges his inner Astaire with private dance lessons, explores the endless popularity of ballroom dance in America and performs the classics “Change Partners”, “Singin’ in the Rain,” “Shall We Dance” and “Let’s Face the Music and Dance.”

Episode 3 of Season 3: On the Air

Today, “American Idol” is the country’s biggest music star-maker, but decades ago, the Golden Age of Radio fulfilled the idol-making role in the U.S. Feinstein traces the phenomenon with archival clips of Bing Crosby, Cab Calloway, Kate Smith and many others. He visits with TV and stage star Rose Marie (best known as “Sally Rogers” on “The Dick Van Dyke Show”) and learns about her career as a highly paid child radio star named “Baby” Rose Marie. On his own NPR program, Feinstein showcases the virtuoso talents of classical superstars, including violinist Joshua Bell and pianist Jeremy Denk. Finally, he discovers a lost radio program that featured Rosemary Clooney, and recalls his own memorable duet with her.