Lester Johnson Works on Paper

Provincetown Art Association and Museum

By: Charles Giuliano - Apr 10, 2017

Lester Johnson from the Permanent Collection

Curated by Christine McCarthy

Provincetown Art Association and Museum

460 Commercial Street

Provincetown, Ma 02657

January 20 to May 7, 2017

As a young artist, for Lester Johnson (1919-2010), summers in Provincetown, and interaction with like minded artists, were crucial in developing a bridge from abstract expressionism and a return to figuration that evolved as the movement of figurative expressionism.

The sixteen works on paper that comprise the small but evocative exhibition Lester Johnson from the Permanent Collection provide rarely seen early works, starting in 1951. They represent examples of how the artist was looking at and deconstructing or abstracting seascapes, facades of houses, and breaking down the human figure.

The works were gifted to the PAAM permanent collection in 2016 by Josephine Johnson and the family of the artist. The selection aptly reflects what Johnson created when he resided in the artist’s colony in the early 1950s. He had yet to execute the large, drippy, expressionist heads or men in hats series which first earned critical notice in New York. His emerging reputation was such that he was singular as a member and participant in the activities and debates of the Artists’ Club. It was the bastion and think tank for abstract artists of the New York School.

With a handful of Provincetown’s artists- Jan Muller, Tony Vevers, Bob Thompson, Jay Milder, Emilio Cruz, Red Grooms, George Segal, Earle Pilgrim among others- he was at the epicenter of artists looking for a way back to the figure. This is a movement which has been largely overlooked and widely misinterpreted in the mainstream of theory and criticism.

The selection of works on view, in intimate scale and with economy of means, reveal in nuggets of visual information the genesis of ideas that would evolve during a long and productive career.

In a riveting manner these works evoke conversations with the artist in New York and his Connecticut studio that were part of the research for a catalogue essay for his traveling exhibition organized by the Westmorland Museum of Art.

Lester referred to what he was doing in Provincetown and exhibitions at the seminal Sun Gallery but, other than slides, there were few if any actual works to view and discuss.

The current exhibition fleshes out and enriches those critical dialogues.

It is interesting that his first Provincetown exhibition (1953) was in the shop of jeweler and artist Earle Pilgrim. I had known Earle and his wife Lily in New York during a time of relative inactivity. By then his work was essentially forgotten. I brought it back into focus by including it in an exhibition I curated for the PAAM “Kind of Blue: Benny Andrews, Emilio Cruz, Bob Thompson and Earle Pilgrim.” It surveyed the work of a generation of African American artists in Provincetown.

When Earle gave up the space at 393 Commerical Street it became Sun Gallery directed by Yvonne Andersen and Dominic Falcone. They showed a wide spectrum of work but many of the figurative expressionists were a part of their program.

For a number of years Lester taught in the graduate program of Yale University. He told me about his efforts to teach drawing by breaking down prior conditioning. The focus was to release unlearned primal energy. This entailed having students draw with the other hand. Instead of starting with the head and working down to create a figure he had them start from the feet working back to the head. This entailed new challenges and ways of observing and conceptualizing the figure.

One can see that approach in the works currently on view.

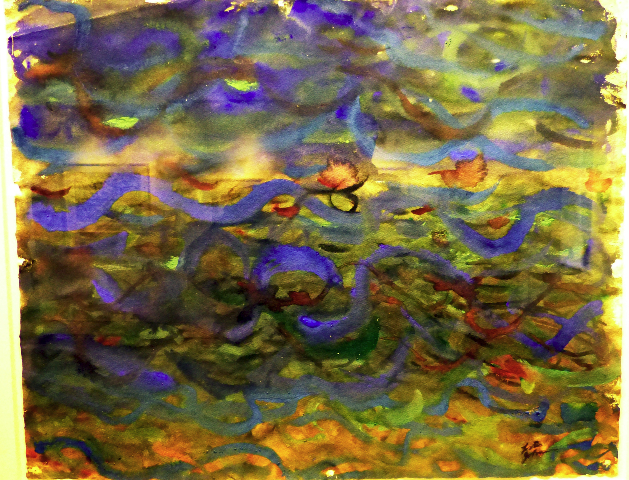

Primarily, he worked with watercolor creating quick, primal and intuitive observations of Provincetown landmarks. The signature piers are rendered as patterns of bold, thick black strokes. While retaining the essence of the subject, its wharfness, the frenetic patterning is liberated into something other. It pushes toward but stays this side of abstraction. In that regard he identifies a key aspect of figurative expressionism. In essence, he reverses the paradigm of modernism by seemingly retracing the steps from abstract art back to figuration.

While artists from Mondrian, Malevich and Kandinsky, to Pollock progressed from nature to abstraction the work of Johnson darts back and forth over that boundary line. It is an act of generational defiance against Pollock’s statement that “I am nature.”

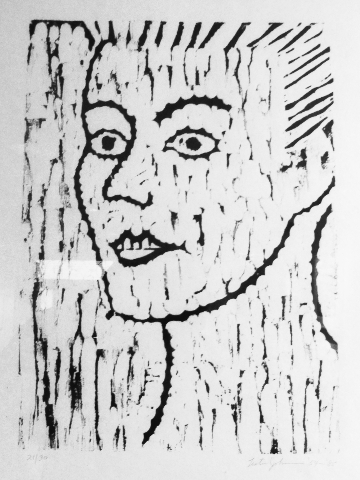

The Provincetown period represents Johnson’s observational phase. He is looking at, analyzing and reducing what he sees. In later periods of the work, for example the seminal giant heads, he was free from observation. When creating those looming, energized, exploding faces and figures he was liberating his psyche of embedded archetypes. The process of painting the works was charged, cathartic and psychic. He was channeling the figure which was emerging from him in a compulsive, frenetic gestural attack on the canvas. For me this was his most paradigmatic work.

As the ideas and techniques evolved, by the 1960s and beyond, his approach became more conceptual, decorative and mannerist. There are elements of fashion, for example, the colorful patterns of then popular printed dresses designed by Emilio Pucci.

In these works from the Provincetown period we experience Johnson at his most instinctive and primal. They convey the white light energy of the heat oppressed mind. The works explode onto their supports.

These ideas returned with him to New York. An Acme Gallery exhibition included one of his early Bowery paintings (circa 1951) abstracting the façade of a loft building. There is an immediate connection to more simple deconstructions of houses in Provincetown. The Bowery painting, an oil painting on canvas, is more ambitious and strives to push further what had started as quick and intuitive sketches.

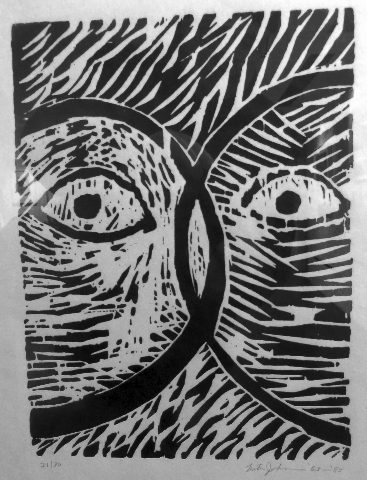

The greatest discovery of this exhibition is a series of six woodcuts. The blocks were created from 1953 to 1957 and printed as an edition of 30 in 1985.

Here most vividly he evokes the influence of German expressionism by exploring their signature medium and raw nerve technique. A departure is an even greater commitment to the essential and primitive. There is a difference in the images from explicit heads to staccato hacks and slashes creating all-over, seemingly random marks and patterning. Looking closely at the most extreme examples of this approach one finds an embedded, frenzied, post existential, nuked and charred man or corpse. This was parallel to what he was doing with the figure in the seminal, experimental Bowery paintings.

More than the widely discussed return to the figure the tormented frenzy evoked in the woodcuts and watercolors of this body or work represents a vision quest to find the essence of inner humanity.

It is the kind of reckless and iconoclastic work that can only be executed by a tormented, young and poetic artist in a desperate search for identity and soul. These works are the visual equivalent of Rimbaud’s Une Saison en Enfer.