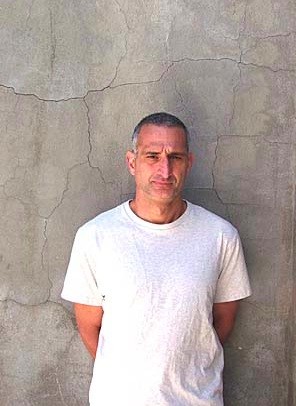

Christopher Wool at the Art Institute

Chicago Celebrates a Native Son

By: Susan Hall - Apr 11, 2014

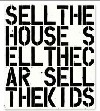

Thirty-one letters by Christopher Wool brought more than 26 million dollars at an art auction last fall. Visually the letters are compressed, blob-like, stacked. Musically, each of the three phrases has a sound which is considered one of the most beautiful in the English language: sell or cell. Two hard 'c' sounds (actually a ‘k') break up the beauty.

The phrase startles because selling the kids is verboten. Do you have to know the title, Apocalypse Now, to react?

The joke about conceptual art, although 26 million dollars is no joke, is the answer to the question: “Why do conceptual artists paint?” “Because it seems like a good idea.”

Is “good” defined as pleasing the mind, the ear, the eye or the wallet?

What is true about the work of the pre-eminent American artist Christopher Wool is that it hangs well on the wall. This was not as evident at the Guggenheim Museum in New York where a major retrospective of Wall’s work was displayed last fall.

Now at the Art Institute in Chicago, Wool’s birth city, the work is more satisfying. It’s impact more direct.

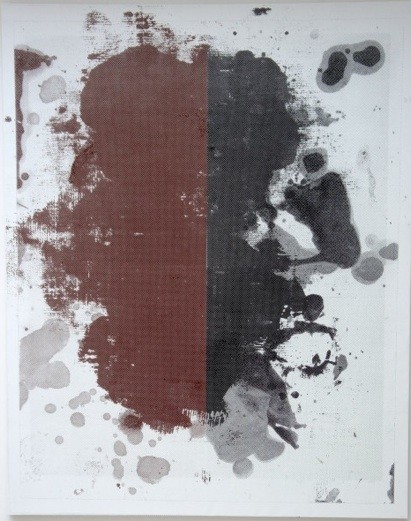

Blobs sent to the Venice Biennale in 2009 are the first work you see. For the past decade, Wool has worked in layers. A conversation takes place between each layer. Ben Day dots, a favorite of pop artist Roy Lichtenstein, are both acknowledged. Wool uses them. And then they are trashed.

The dots are painted over with broad painterly brushstrokes, the opposite of Lichtenstein’s brushstroke in the 777 Seventh Avenue mural in New York. In that mural, the brushstroke is completely artificial. Not a brushstroke at all. It is cold, like all of Lichtenstein’s work, except the room drawings. GOAWAYROY.

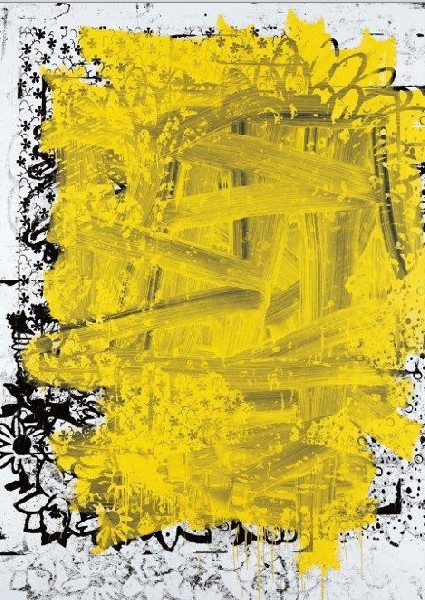

If Wool’s images in the show are appropriated, they are from my young artist friend, Adeline, who is three. Bold flowers, some budding open, some big petals surrounding a capitulum. CAPTHECAPITULUM.

Stenciled wallpaper flowers and vines may be appropriated from CLIPART.

But anything that is artificial, created by others, is satisfyingly defiled. On some layers there are narrow strokes of black paint, sometimes dripping, which twirl like a tangle. The blob appears frequently and is my favorite image, reminiscent of Clyfford Still.

Like Still’s exit from the stultifying New York art scene, Wool now spends time in Marfa, Texas, land of the big sky.

The feeling of Texas was once described by Supreme Court Justice Sandra Day O’Connor who grew up on a ranch. She talked about standing at the front door of her home and watching a storm come in. It took days to finally arrive, because you could see so far. Even, you imagined, beyond the horizon. For a sense of our smallness in the universe, and also for images that impact, there is nothing like Texas. We will see how it impacts on the city boy Wool.

As a word person I was attracted to the piles of letters. TRBL is a favorite. I did not find the assembled words moving until I actually tried to pronounce the words without vowels. The struggle compelled.

But the newer work, often enamel on aluminum, draws you into a trio conversation between the layers. Consider the copied image. Watch how four panels are mismatched. Try adding a stroke. No, strike that.

Wool is more than a conceptualist. He is a conversationalist, layer to layer. And the conversation is about art.