Namibia: Part Four

Damaraland

By: Zeren Earls - Apr 13, 2015

Flying 120 kilometers inland from Walvis Bay, our single-engine turbine headed to Damaraland, maintaining a cruising altitude of 12,000 feet. During the hour-long flight, the scenery below changed from wide open sandy plains dappled with shadows to a dry riverbed, then to rocky red- hued terrain. As we approached sandstone cliffs and table-top outcrops, the landscape took on the appearance of a multi-hued painting.

Upon landing we were driven atop a rocky hill to Doro Nawas camp, our home for the next three nights. The camp staff met us with refreshing washcloths and a cold fruit drink with an unfamiliar flavor, which turned out to be prickly pear juice. The outside temperature was 40º C; drought was prevalent.

The campsite, built on ancient volcanic rock, had spectacular views of the flat-top mountains of the Etendeka range to the north and savannah and grassland below. The design and décor of the main lodge as well as the individual tents, made of stone and canvas, blended in with the rugged surrounding landscape. After a lunch of butternut squash soup, spaghetti, and ice cream, followed by a short rest, we went for a ride to look for bush elephants, unique to the region.

Having adapted to the desert’s dry, sandy conditions, bush elephants are used to walking long distances and are able to go without water for several days. Small in size, they have longer front legs than other species and wide feet, with four toes in front and three in back. Knowing that they move depending on the availability of food and water, our driver decided to pull over by the roadside and wait. Soon after, a small elephant pushed her way through the bushes, crushing some underfoot, and opened up a downhill path for her baby. Then the two walked along the road, stopping to feast on branches along the way.

Other wildlife we spotted on this drive included springbok, guinea hens, and aardvarks, whose presence can be detected by the distinctive holes they leave in the earth. Circles on the ground signaled the presence of a kind of termites which eat the roots of plants underground as they build their mounds, leaving the surface above barren. As the day wore down, the wind picked up, causing me to roll down my sleeves, which would have been unthinkable an hour earlier. We returned to the lodge to enjoy a sundowner on the rooftop terrace with a spectacular view of the surrounding mountains.

Dinner was in the lodge’s inner courtyard, decorated with lanterns around an open pit fire. The menu was announced at each table in English and again in Damara, a Khoisan language spoken locally. Following an appetizer of calamari salad served at the table, there was a choice of steak, sausage, or fish in foil from the outdoor grill, accompanied by zucchini, cauliflower, and rice.

As I descended to my tent after dinner via a stepped plank and paths delineated with rocks, my flashlight also seemed to assist in lighting a way through earth’s history. Upon entering the tent, I found a hand-made card on the bed wishing me good night: “…as long as your heart is true, sweet dreams will always be with you; (…) hope your day was quite all right and now we bid you a lovely night.” Accompanied by such sentiments and snuggled in a tent made partially of sturdy ancient rock, I fell asleep right away.

In the morning we were awakened at 6:30 for an early breakfast and departure to Twyfelfontain at 7:30. A UNESCO World Heritage Site, the area is a large concentration of Stone Age petroglyphs depicting African wildlife. The name, meaning “Doubtful Fountain”, was given by a farmer who was doubtful about a local spring providing water for his cattle indefinitely. Guided by a park ranger, we climbed around the red sand-stones, spotting engravings of giraffes, rhinos, elephants, birds, and a myriad of other animals, large and small. An engraving of a lion with a human hand at the tip of its tail is a popular site; the hand is considered the engraver’s signature. Of the approximately 2500 engravings, some indicate life in the area as early as 6000 years ago.

Driving down a path afterwards, we arrived at a valley of rock formations called Organ Pipes, produced by dolerite sedimentations 125 million years ago, when molten rock cooled vertically into polygonal cross sections. From a distance the gray-and-pink-hued basalt columns of different heights looked like a crowded urban block in a cityscape set against a hill. Although I would have liked to take a small broken piece as a souvenir, I resisted the temptation, respecting the environmental protection law written into the Namibian constitution.

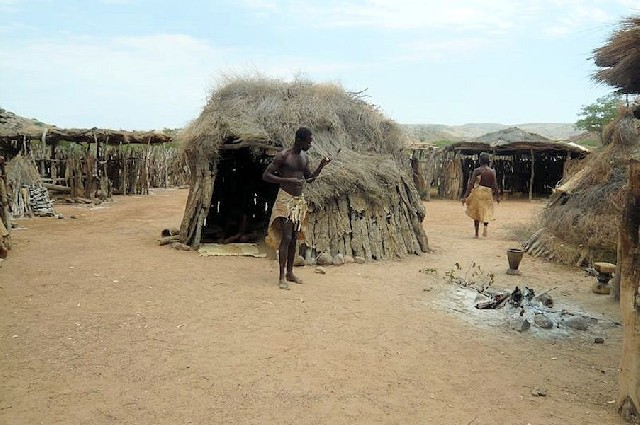

Our next excursion was to the Damara Living Museum, an open-air village of straw-thatched huts set up to show the past ways of life of the Damara people. A group of men and women, who share the daily admission fees collected, work here to demonstrate ancestral ways of not long ago. We were met at the gate by a young woman clad in a skirt of animal skin, with many strands of ostrich eggshell beads hanging over her bare chest. The young man who accompanied her had a piece of animal skin tied around his waist, with a belt of bones strung at different lengths to cover his private parts.

Moving from hut to hut, we learned about the use of herbal remedies, and watched women carve, cut, and shape shells and wood into jewelry, and men make tools and engrave animal skin. Starting a fire was a laborious process, beginning with the filling of a hole in a piece of wood with powdered dung, which was then pounded hard with a stick until it began smoking, and ending with the addition of a small amount of hay to get the flames going. We also watched men play a game, taking turns collecting stones into rows of holes on the ground. At the end of the visit, our hosts, singing and dancing, sent us on our way.

We refueled by stopping under the shade of a big tree for a picnic lunch, prepared by camp staff, who had taken care of every detail, including cloth napkins. After enjoying fish cakes, grilled sausages on skewers, and a variety of salads — bean, corn, and potato — followed by a plate of sliced fresh tropical fruit, we returned to the campsite to rest, as it was getting very warm.

During a nature walk late in the day, we learned about bush plants such as mopane, ebony, and others poisonous to touch. Ebony has very thin leaves, which natives use as toothbrushes. We encountered a herd of goats searching for food on the sparsely grassed slopes, while lizards scrambled for a place to hide. We returned to the lodge in time for a sundowner and another delicious dinner — lentil soup, game steak or chicken cordon bleu with mushroom sauce, wild rice, broccoli, butternut squash, and cheesecake with strawberry sauce. Afterwards the staff entertained us with spirited singing and dancing.

On our last day in Damaraland, we headed out to a nearby forest of fossilized trees, buried a million years ago by floods in an old riverbed. Over the years the petrified trunks, mixed with varied underground minerals, have taken on striated colors. The longest trunk is 35 meters long.

Amidst this petrified wonder, we were introduced to a unique cone-bearing plant called “welwitschia mirabilis”, endemic to southern Angola and the Namib Desert. The plant has two wide leaves, a stem base, and roots. The original leaves are never shed, but continue to grow close to the ground at a rate of about one centimeter a year. The plant’s age is determined by the length and width of its leaves; its estimated lifespan is 400-1500 years. Female welwitschia is larger in size than its male counterpart. I photographed a 100-year-old female plant.

A visit to the settlement of the Riemvasmakers tribe in the village of Deriet revealed the complexity of past relations between Namibia and South Africa. Due to tribal wars in Namibia, the ancestors of this tribe had moved to South Africa; however, during apartheid they had been sent back to their ancestral land and settled on farm land, left to their own devices to survive. At the time of our visit, only a few people over the age of 60 were around; younger people had various jobs in the city, while their children, ages 6-16, attended a boarding school.

Oma (“Grandma” in Afrikaans), a 79-year-old woman and the oldest in the settlement, showed us her modest living quarters and her vegetable garden. Her small bedroom was a little larger than her double bed; her kitchen had a wood stove and an area for supplies and a cupboard to store dishes. Her sitting area had straight-back chairs around a small table with candles, and a goat-skin rug on the dirt floor. She shared a freezer with one other person, with whom she was driven to the city to buy essentials once a month.

In her little garden, Oma grew tomatoes, peppers, and herbs. She complained of jackals eating her goats and elephants coming by for water. A pump drew water from underground to fill water tanks; a solar panel had recently been installed to operate the pump. As I bid goodbye, the woman’s beautiful long black-on-white print dress with a red apron in front stood in stark contrast to my neutral-colored desert outfit. We were two people separated by only a year in age, but worlds apart in our destinies.

On the drive back to the lodge, we saw a group of elephants breaking branches off trees to strip the barks for food, which is the only part they eat. There were also baboons, springbok, and a variety of birds at a distance. Knowing our next destination was Etosha National Park, known for its teeming wildlife due to its many underground springs, we called it a day, not to miss our last sunset from our rocky perch. (To be continued)