Revolutions are tricky business. As we’ve seen in recent years, in the example of the Arab Spring, the Syrian conflict, and even recent events in the Ukraine, revolutions inspire hope and optimism. Yet when their aims get muddied, their motives become sullied by realpolitik, and they devolve into chaos, violence, and endless bouts of recrimination and revenge, they also engender confusion, cynicism, and despair. A revolution shines light on the oppressiveness of totalitarian regimes and provokes our individual sympathy for the people who suffer under those regimes; at the same time, it often also reveals the complicity of our own national foreign policy in keeping those regimes in power in the name of regional stability.

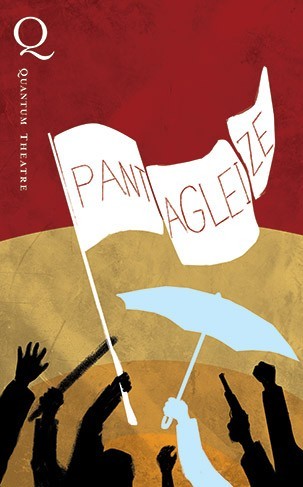

Contradictions abound, and it’s often nigh impossible to figure out, in a given context, who the “good” and “bad” guys are, especially when there are many ideologically opposed factions working together temporarily to topple an unpopular dictator. Moreover, revolutions in other places – or even close to home, in the form of “Occupy,” for example – raise uncomfortable questions about the extent to which our own freedoms and democratic institutions are under threat from repressive forces that are imperceptibly eroding what we consider basic rights. Pantagleize – Jay Ball’s smart adaptation of Michel de Ghelderode’s 1929 play of the same name – is a deeply cynical, outrageously comic, and highly provocative play about such challenges and contradictions of democratic revolutions.

Ghelderode’s original play — which he labeled a “farce to make you sad” – deployed vaudeville and clowning to express his deep cynicism about the limits of idealism and the contradictions inherent in any attempt to overturn a brutal dictatorship and establish democracy in its place. His play is windy and wordy, very much of its time and place, and something of a difficult slog for the modern reader of drama (it’s rarely produced). But the essential conundrum it poses regarding the challenges of the revolutionary impulse is perhaps more pressing now than at any other time in history. Happily, playwright Jay Ball has reimagined and adapted Ghelderode’s play into an idiom and style that concisely and wittily exposes the realities of power, politics, and militarism in the modern world, while still retaining the clowning and absurdism that marked Ghelderode’s original work.

In Ball’s adaptation, Pantagleize (Randy Kovitz) is a past-his-prime hippie poet (loosely based on the beat poet Allen Ginsburg) who has been invited to some vague eastern European country (loosely based on Czechoslovakia) to reign for a day as “King of May” during the annual May Day celebration. A former cultural revolutionary himself, Pantagleize has, by his own admission, “outgrown his capacity for outrage”; lacking both interest in and knowledge of his host country’s repressive political situation, he’s come for fun, booze, and sex. His accommodating driver, Baboosh (Abdiel Vivancos), takes him to a bar, liquors him up, and introduces him to his circle of friends, all of whom (unbeknownst to Pantagleize) are proto-revolutionaries, just waiting for the right moment to rise up against the ruthless dictatorship of El Prezidente (Tony Bingham). Shortly thereafter, the drunk, unwitting Pantagleize precipitates that moment by inadvertently shouting out the revolutionary catchphrase as part of his “coronation speech,” and all hell breaks loose.

The revolution is disorganized and chaotic; Pantagleize bungles his way through the various tasks assigned to him; an accident-prone secret policeman named Krip (the hilariously rubber-jointed Weston Blakesley) shadows the group of conspirators using a wild variety of disguises; the regime cracks down with ruthless cruelty on the revolutionaries; and they, for their part, lose sight of the aims of their revolution and devolve into ideological infighting about what system they will put in place of the dictatorship when the revolution is won. If you’ve paid any attention to the international news in the last decade the conclusion of this hapless revolution will not come as a surprise. What may surprise you, though, is (a) how much comedy this excellent ensemble wrings from their serious clowning within the situation, and (b) how much your laughter sticks in your throat in the end.

Director Jed Harris has guided the creative team into wild and wonderful performance territory, blending slapstick, commedia dell’arte, farce, satire, mockery, and verbal irony in generous amounts to fabricate a world that is at once ridiculous and terrifying. The “Absurdistan” atmosphere is set from the moment you walk in the door, as you are scrutinized by a hostile border guard before your ticket is stamped to allow you entry into the performance space. Scene designer Tony Ferrieri has deftly transformed the setting – an abandoned mailing facility – into the kind of bleak, bureaucratic, characterless space familiar to anyone who has ever traveled behind the iron curtain (or been detained by customs in any US airport). Windows serve as projection screens on which suitably low-tech projections (by Kevin Ramser) flicker, and they are put to particularly good use in an ingeniously devised long-distance video conference between the Prezidente and his buddies-in-oppression Augusto Pinochet, Muammar Gaddafi, Idi Amin, and (brace yourself) Margaret Thatcher (all played by the versatile and comically adroit Tony Bingham).

Elizabeth Atkinson’s sound helps lend authenticity to the show’s behind-the-iron-curtain “vibe.” Likewise, Susan Tsu’s costumes capture spot-on the strangely “off” quality of pre-1989 Eastern-bloc clothing, which seemed somehow stuck in the seventies, and the variety and originality of costumes in this production adds immeasurably to its comic punch. Inhabiting those costumes is an ensemble of some of the most comically resourceful actors I’ve seen on a Pittsburgh stage, including (in addition to those already mentioned in this post) Lisa Ann Goldsmith as the revolutionary ringleader Rachel, Sam Turich as the gruff but loveable Pest, Erika Strasburg as Blanka, and Max Pavel, Kimberly Parker Green, and Alex Knell in multiple roles. The ensemble works adeptly in an insanely out-there comic register, except (fittingly) for Kovitz, who, as the straight-man foil to all the madness, serves in the end as a register of our own dismay and horror, and a reminder of the moral and social danger of losing our capacity for outrage.

Reposted with permission of Wendy Aron of The Pittsburgh Tatler.