Colombia: Part Three

Cartagena

By: Zeren Earls - Apr 17, 2014

Cartagena is a port city on Colombia’s Caribbean coast; we had to fly via Bogota to get there from Pereira. Upon arrival at the airport we found out that our flight was delayed when an attendant stood up on a chair to announce the delay in Spanish. Having to wait a couple of hours for a 45-minute flight, we landed in Bogota, only to find that the Cartagena flight was delayed as well. Thus we had to spend the day in transit, landing at our destination at dusk.

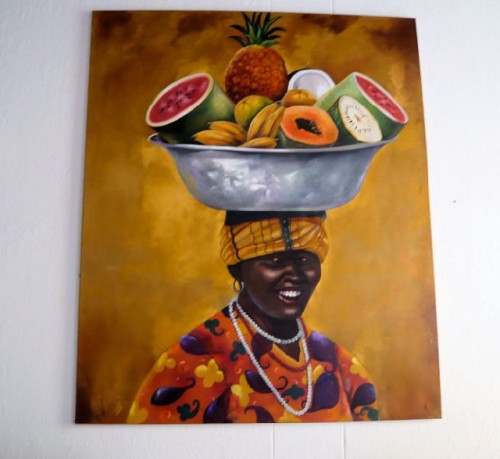

The lovely Bantu Hotel in the old center of Cartagena quickly helped me recover from the day’s airport exhaustion. A pet toucan fluttered about in the courtyard of the colonial mansion, while a wall tableau of a palenquera — an Afro-Caribbean woman in traditional garb balancing a load of fruit on her head — welcomed guests with a smile. My spacious room with old ceiling beams opened to a bathroom with brass fixtures and double showers. Enchanted with my room’s features, I looked forward to exploring the neighborhood for other historic buildings within the Ciudad Amarullada, or Walled City, encircled by twelve-foot stone walls.

Following dinner at a sidewalk restaurant nearby, we went for a chiva ride to enjoy a night time view of the city. Chivas, meaning “goats,” are old painted school buses used for public transportation; they have parallel bench seats, cutaway sides, and a luggage rack on top. We toured the peninsula, gazing at high-rises shimmering by the water’s edge, while listening to musicians play salsa tunes in the back of the bus.

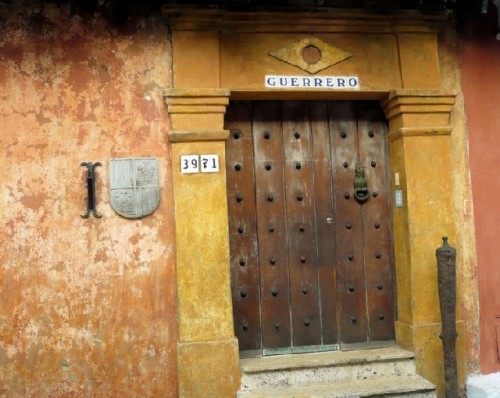

A morning walk of the old city within walls, built by the Spanish for protection from would-be invaders, took us through narrow streets, which still retained their colonial names on embedded wall tiles. Houses with painted facades, antique door knockers, and wood-beamed windows with bougainvillea spilling over or vine-covered balconies lined the streets. Lively plazas with shade trees teemed with people.

A visit to Bocagrande, the modern hub of the city between Cartagena Bay and the Caribbean, gave a very different picture. Here high-rise condominiums and hotels with a water view lined the edge of the peninsula. Old-money families, mostly of Spanish descent, lived in this neighborhood; they were out and about jogging or walking along palm-fringed paths by the shore.

Our beach front excursion was followed by a visit to the Joyeria Caribe, the Emerald Museum and factory, where we were briefed about emeralds, for which Colombia is famous. After seeing emeralds in their natural form, embedded in chunks of rock, we visited the workshop, where jewelers polished gems and set them into rings, brooches, and other items. I walked through the gift shop quickly, as I did not intend to buy emerald jewelry.

Meeting up with Francesca, our local guide, we exited the city gates by the clock tower on foot and rode up to La Popa, Cartagena’s highest hill at 486 feet, topped by an imposing 17th-century convent. The Convento de Nuestra Señora de la Candelaria was founded by Augustine monks in 1607. It no longer serves as a convent, but remains a pilgrimage site for those who come to pray to the Virgen de la Candelaria, Cartagena’s patron saint. The two-story structure has a picturesque arched courtyard with flowering trees and out front a very large cross, commanding a sweeping view of the city below.

Descending the hill, we walked by the Teatro Heredia, a performance hall built in 1911, and continued on to the San Diego quarter, where many colonial mansions have been renovated. Walking through quaint streets with balconied buildings also offered a wonderful display of antique door knockers, the size of which seemed to vary with the prestige of the owners. Arriving at Bolivar Plaza, the main square of the old city with a life-size statue of the liberator, the group dispersed for a free afternoon.

On the east side of the Plaza is the Gold Museum, specializing in pre-Colombian gold by the Zuma Indians of the Caribbean coast. The museum’s collection ranges from gold pieces depicting animals, birds, and fertility symbols to urns for burying possessions of the dead. On the west side of the square is the stone entrance to the Palacio de la Inquisición, which today houses the Museo Histórico, displaying instruments used to torture suspected heretics during the “Holy Inquisition” in the 17th and 18th centuries, in addition to documents of Cartagena’s history.

There are numerous sidewalk artists in this area. From one of them I purchased a signed watercolor of balconied houses with bougainvillea spilling over. In the crowd of vendors, two palenqueras in colorful outfits, selling fruit, stood out. I bought two bananas, one from each, in exchange for a pose for my camera. Considering the bananas my lunch, I walked back to the Bantu Hotel as a respite from the heat, which was in the 80s, but felt hotter because of the humidity.

After a rest I was back on the street, this time walking to the northeast of the center, where Las Bovedas, a row of 23 storerooms built into the city walls in the late 18th century, now serves as a craft market. Shops filled with crafts included sombreros, totumo maracas, and mochilas — indigenous shoulder bags.

In the late afternoon several of us walked with Paulo to a club to experience local cumbia dancing, derived from “cumbe,” a Guinean dance form. Cumbia began as a courtship dance among African slaves. Infused with West African rhythms, patterns of the complex folk dance invoke ankles weighed down with shackles. Over the years the dance has evolved in Cartagena, incorporating elements such as Spanish dress and indigenous cane flute melodies. We watched a young couple — the woman in a long flowing skirt, the man in a white shirt and sombrero — pass a torch of lit candles back and forth as they expressed their love for one another. The program ended with a spirited salsa dance.

Dinner at La Cevicheria, specializing in seafood, was memorable — a casserole of shrimp and squid in cheese and tomato sauce, with a dessert of pan-fried white cheese and guava nectar.

On our final day in Cartagena we continued our walks through streets and plazas, which further revealed the vibrancy of the city. A coffee vendor, licensed to ensure his product was safe to drink, commanded a street corner; typists under the shade of umbrellas kept busy preparing documents for people as they waited, while other entrepreneurs rented cell phones by the minute. Flower and produce stands complemented the colorful panorama.

Two huge bronze statues of Pegasus stood in front of the Convention Center, and a monument in Carrera marble of a woman holding her palm toward the sea faced the harbor, with a Latin inscription saying “Don’t touch me,” as if to warn future invaders. At another plaza a seated statue of Cervantes with plume in hand signaled the presence of book stalls nearby. Stacked with books, portable stalls invited passers-by to browse, while paper cutters hand-trimmed worn-out books for resale.

Getsemani is a working-class extension of the historic center and is separated from gentrified neighborhoods by Avenida Venezuela, a broad, modern thoroughfare. Francesca led us on a tour of the Afro-Caribbean neighborhood where she had grown up. Graffiti covered the facades of many of the run-down houses, some of which portrayed the layout of the interior and the people living there — a project created by young people under the direction of a local artist. We stopped to talk to an old woman sunning her arthritic legs in the hope that the warmth would heal her pain. Entrepreneurs have moved in to upgrade the neighborhood; some people have been forced out of their homes to make room for a luxury hotel. The gentrification of Getsemani is very much in the air, despite the residents’ fight against it.

The San Felipe Fortress is on a hill a short distance to the east of Getsemani. It is the largest of the forts built by the Spanish to ring the city for protection from land or sea. Built by slaves in 1533, it was extended and rebuilt over 200 years, most recently in 1763. Named in honor of the Spanish king Philip IV, the fortification consists of a series of walls, wide at the base and narrow toward the parapet, forming a sloping defense system with guns commanding the whole bay. A complex maze of tunnels facilitates passage within the castle beyond its grand entrance. Below the castle stands a statue of Don Blas de Lezo, a Spanish admiral who successfully defended the city against British forces in 1741. Declared a UNESCO World Heritage Site, along with the city’s historic center, in 1984, the castle now serves as a venue for social and cultural events hosted by the Colombian government.

In another neighborhood, we drove through impoverished streets for a home-hosted lunch. On the way we picked up a beautiful young English-speaking woman with Afro braids and braces, who helped interpret over lunch. She turned out to be our host’s niece and commuted to college daily by bus from her humble surroundings. Our host family of four lived in a two-room house and served us a delicious lunch out of a very modest kitchen. Following a platter of fresh mango, pineapple, and watermelon came chicken, accompanied by beans, rice, and a green salad topped with sliced tomatoes and onions, all attractively arranged on individual plates. For dessert we enjoyed a napoleón — vanilla pudding layered with berry sauce.

In the same neighborhood we visited an after-school program of a local foundation supported by the Boston-based Grand Circle Foundation. The program, which aimed to keep children out of harm’s way after school by engaging them in meaningful activities, underscored the challenges facing modern-day Cartagena. The place seemed to be a haven for youth, ranging in age from elementary to high school. We met one of the artists who worked with the youth and exhibited there.

Our final evening in Cartagena began with a carriage ride through the walled city’s night time glamour and ended with a festive farewell dinner in an upscale local restaurant. On this occasion we were also celebrating the birthday of one our group members; Paulo decided to include me in the celebration, although my birthday had been at the beginning of the trip. My dessert plate arrived with a Spanish “Happy Birthday” dribbled in chocolate —another memorable evening indeed.

My flight back to Miami required an earlier departure from the rest of the group, who continued on a post-trip to Ecuador, a country I had enjoyed exploring with my sister five years before. As my flight took off, I could detect through the misty air the piers jutting out to the Caribbean and the high rises of Cartagena at a distance. These images and many more have now joined the indelible memories of my travels to distant lands.