Otto Piene at Sperone Westwater

Light Ballet and Fire Paintings, 1957-1967

By: Charles Giuliano - Apr 18, 2010

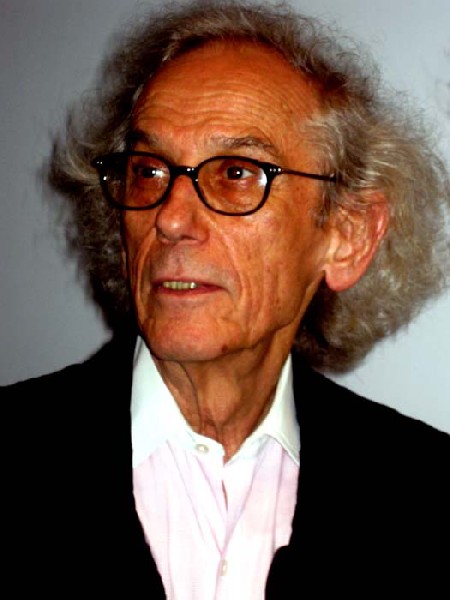

Otto Piene

Light Ballet and Fire Paintings, 1957-1967

Sperone Westwater Gallery

415 West 13 Street

New York City, 10014

212 999 7337

April 6 to May 22, 2010

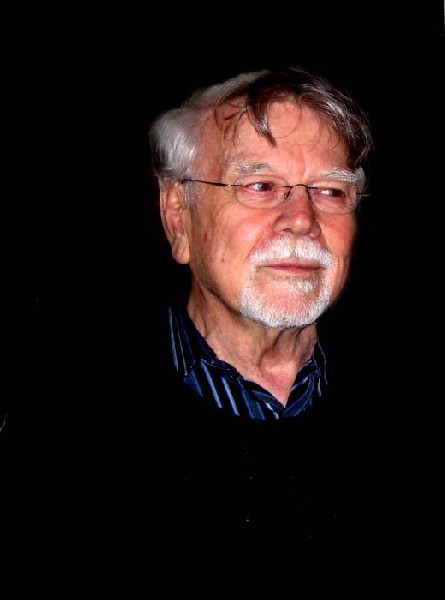

In 1957 Otto Piene (born 1928 in Bad Laasphe and raised in Lubbecke, Germany) and his colleague, Heinz Mack, formed group Zero. In 1961 Gunther Uecker started to exhibit with them. The Zero movement has been the focus of many European exhibitions, particularly in the past decade. But the work of these artists who explored experimental media and techniques has remained relatively obscure in the mainstream of the American art world.

The Sperone Westwater Gallery organized Zero NY in November 2008 accompanied by an extensive catalogue. For ten years Astrid Hiemer worked with Piene at the Center for Advanced Visual Studies (CAVS) at MIT. Astrid and I wrote about that important exhibition. It was included on year end lists of the most important New York exhibitions of the 2008 season. Link to Hiemer review

Through May 22, Sperone Westwater is exhibiting Otto Piene; Light Ballet and Fire Paintings, 1957-1967. Most of the works on view have been borrowed from private collections. The project focuses on a formative decade of the artist's production. By presenting this vintage work the gallery is creating a context for the 700 page catalogue raisonne which has gone to press.

During the recent opening, many former CAVS fellows and colleagues of the artist attended. We discussed the work with Jane Farver the director of MIT's List Center for the Visual Arts. She remarked at how fresh and contemporary the work felt. Indeed, nobody would be surprised had this been an exhibition of work by an emerging artist. Actually, that precisely describes Piene at the time in which they were created. It has taken decades to catch up to the immediacy and boldness of that vision. Next year, during the 150th anniversary of MIT, Farver is planning a program exhibiting artists who have worked at the Institute. One of those projects will focus on Piene and Hans Haacke.

Recently, Piene was included in the 2010 DeCordova Biennial in Lincoln, Mass. Compared to major museum exhibitions it was not of great significance. But it was a landmark in the sense of local recognition of an artist and movement virtually ignored by Boston's infrastructure of museums. Although Piene has lived and worked in Boston (Groton), commuting to a studio in Dusseldorf, since 1968, his work and that of CAVS Fellows have received little or no recognition from the Institute of Contemporary Art, the Rose Art Museum, or the Museum of Fine Arts. In that sense the DeCordova deserves credit for correcting an egregious oversight.

From 1968-1971 Piene was the first Fellow of CAVS which was founded by Gyorgy Kepes (1906-2001). From 1974 to 1994 Piene was the director of CAVS. In Europe the work has been shown at documenta, in Kassel, Germany in 1959, 1964, and 1977. The 1977 documenta project Centerbeam involved a team of fellows from CAVS. The following year it was installed on the Mall of Washington, D.C. Piene arranged the German pavilions in 1967 and 1971 for the Venice Biennales. For the closing ceremonies of the 1972 Summer Olympics, in Munich, Piene created the sky art work Olympic Rainbow.

Today it is possible to view the early work of Piene and the Zero movement with appreciation and clarity. There is a compelling logic that falls within the rational paradigm of the Apollonian pursuit of beauty and purity of aesthetic experience. We can understand that the technologies involved, and the interest in process and materials including smoke, fire, hammered nails, light and air, are less important than the resultant visual experience and pleasure. There is an objectivity to the work that is beautiful to look at. We have come to accept that there might be no other requirement for a work of art. It is what it is.

While this approach makes sense, and is widely accepted today, that was hardly the case when Piene and his peers were coming of age in post war Germany. In 1945, when the war ended, Piene was 17. In the last desperate stage of the war he was enlisted. Following this essay is a statement by Piene in which he recalls that experience. He relates how looking at the night sky illuminated by search lights and bombs would later inspire him to create Sky Art. He describes the uncanny, ironic beauty of weapons of mass destruction.

There is such diversity in contemporary art that is impossible to separate the forest from the trees. No longer are there serious attempts to champion one movement of art over another. During the post war era that was hardly the case. There was jingoism and fanaticism in The Triumph of American Art (Irving Sandler). The New York School was polemicized in the writing of critics like Clement Greenberg. His rival Harold Rosenberg, who coined the term "action painting," discussed "American type painting" and "coonskism."

The decline and fall of the School of Paris was presented in Serge Guilbaut's controversial book with its Marxist conspiracy theory as How New York Stole the Idea of Modern Art. During my evolution as an artist and critic, in the 1960s, it seemed imperative to take a stand. Looking back at those first efforts at critical writing it seems naive and juvenile. It is unfortunate that the growing pains of critics are public and indelible. Now and then I got it right by writing with passion about artists whose work I believed in. But in those early reviews for Arts Magazine, 57th Street Review (a zine produced by Betty Parsons Gallery in response to the lack of NY Times coverage), The Avatar, and later Boston After Dark, I also got it wrong at least half of the time. In posterity critics are evaluated by their batting average.

In New York, during the late 1960s, I thought the focus on art, science and technology shown at Howard Wise Gallery, seemed gimmicky. I never understood the aesthetic of the Park Place artists or the minimalists of Dwan Gallery. My bad. The Pop art of Castelli and Sidney Janis was more compelling. I was intrigued by Bob Thompson, who by then had died, and the artists of the Martha Jackson Gallery.

With hindsight it is possible to look at Piene and the Zero movement as among the many efforts to dig out from under the rubble of post war Europe. Having grown up during the Third Reich there was a mandate to move in another direction away from that insanity. To separate from the Nietzschian notions of the Uber Mensch or the embedded tendency of Northern European, Dionysian art. Its anti classical traditions emanated from the medieval and Gothic. A signifier of that sensibility is viscerally conveyed in the first American Otto Dix retrospective now on view at the Neue Gallerie in New York. The response of Dix to combat during WWII could not be more different than that of a teenaged Piene. Dix is best known for his work created while and after his three years on a machine gun squad during WWI. The artists represent different generations inspired by the same experiences. The senior Dix and young Piene were both pressed into action by the collapsing Reich.

In their departure from the humanistic and sublime, in Piene and Zero, there was a perception that the work lacked emotion. At the time it was difficult to connect with. In the 1960s it was particularly daunting for a generation of art students raised on the mother's milk of abstract expressionism.

Surviving the Holocaust, and living under the shadow of the Bomb during the Cold War that followed, created its own exigencies. The post war generation of artists strove to separate themselves from those emotional entanglements. During the time frame of the current Piene show at Sperone Westwater, 1957-1967, a different mood prevailed in the arts. Miles Davis, in the formative 1955 sessions that comprised his only release for Capitol Records, Birth of the Cool, moved away from the white heat of Bop to a more serene understated form. It would evolve into the modal style that found its greatest expression in Kind of Blue (1959). The era represented the apogee of Theatre of the Absurd, Beckett, and then Pinter. In 1955 Herbert Marcuse wrote Eros and Civilization. In 1966 Susan Sontag published Against Interpretation. And Paul Goodman wrote Growing Up Absurd in 1967.

While Piene, his Zero colleagues, and the Fellows of CAVS embraced advances in technology it comes with a conundrum. Technologies develop with such speed that what is fresh today is obsolete tomorrow. Works produced just decades ago represent enormous challenges for restoration. The fluorescent tubes in Dan Flavin's light pieces from the 1960s are no longer available. The artist was working with standard, off the shelf elements. Those works are now priceless artifacts that collectors and museums illuminate reluctantly.

There is a Bauhaus connection to Piene and Zero. Their concerns may be viewed as a continuation of that trajectory. Laszlo Moholy Nagy brought Kepes with him to Chicago to form the New Bauhaus. Moholy Nagy died in 1946. Kepes eventually came to MIT where he founded CAVS. So there is a direct lineage in this sensibility.

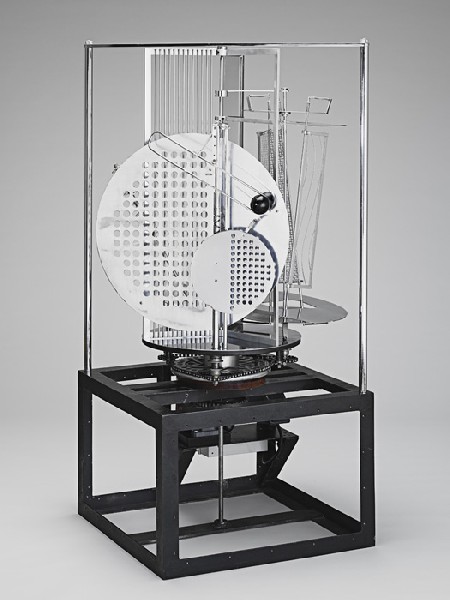

The Sperone Westwater exhibition is divided into two sections. Half of the space is devoted to paintings and works on paper. From there we moved into darkened galleries to view a selection of light sculptures. By current standards they are primitive, even quaint works. Because of the low light levels I was not able to photograph their effects and subtle nuances. Using the flash the installation is fully illuminated. It reveals the forms of the metal sculptures. Inside of which are incandescent light bulbs, mechanical elements, and timers that create a moving program of light and shadow. The concept evolved from Light Prop for an Electric Stage, 1930, by Moholy Nagy, in the Busch Reisinger Museum of Harvard University. In the decades of viewing the work I have only seen it as an object. The museum has never restored its original function as a light machine. One may only sense its impact from documentary photographs.

It is significant that we are still able to enjoy vintage Piene works as they were intended to be seen. There are similar works in collections in need of restoration. Today, that is no small task. But the revival of interest in the work of Piene and Zero, and rise of market value, may inspire those efforts.

It is difficult to say just where Piene, Zero, and the CAVS artists will land during the turmoil of deconstruction and revisionism of the post war and contemporary art history. In this process will the humble and neglected by exalted? When the dust settles who will be the new paragons in the pantheon of art history? There is an industry of scholars and graduate students sifting through the ashes. At the annual College Art Association meetings scholars present their latest findings rather like archeologists. Their papers argue for the reconsideration of this or that individual or movement. How many articles contain the mantra of "new light on" art that may be as recent as yesterday?

Of course this is pursued during an era when, to paraphrase Garrison Keillor "every artist is well above average." We have devolved into the post Greenbergian era of the anti polemical. All art is equally deserving of our attention. In the spirit of political correctness it is uncool to harbor prejudice. Affirmative action has smothered critical evaluation now couched within obfuscating but academically safe art speak. It is not the mandate of the critic or curator to make the work accessible and understandable. The most successful practitioners move along the counter axis. Any tour of Chelsea is a study in catholicism. Even the once chic term of pluralism has eroded from our vocabulary. By now it is a moot point. We have been liberated from a hierarchy in contemporary art.

During the turmoil, ebb and flow of art market trends, there is no option for most artists other than to do the work. Now and then critics and curators catch up. Or not. The fortunate ones are discovered before it is too late. Or they find that their early work is priceless while more recent work remains unsold. In his 1944 novel The Horse's Mouth the author Joyce Carey brilliantly and humorously captured that paradox. His wonderful character, the aged, and impoverished, Gulley Jimson, attempts to steal one of his early works from a museum exhibition. He desperately seeks a wall to paint on; usually abandoned buildings about to be torn down. It is an interesting metaphor of resistance to progress.

How true for those of us who have watched decades and trends float by. Each day in the studio we take our boards to the beach hoping to catch a wave. Surf's up.

Artist's statement by Otto Piene from a 1965. exhibition.

"Piene - Light Ballet"

Howard Wise Gallery, NY

November , 1965

Courtesy of Sperone Westwater

A picture that has left me rarely: the glass smooth North Sea against the light on May 7, 1945. Actually it was the Elbe, the wide, wide river at Gückstadt near Hamburg. After the Labor Corps Infantry Division to which I was attached had been disbanded — I had just turned 17 two weeks earlier — I was on my way home, but not straight away southwards. The end of the war, I supposed, was also the end of all perils, and I made a detour to see the sea for the first time in my life. At noon I walked from the east up towards the dyke and then through a gate: there it was, sparkling like quicksilver, pure light on the water surface, a blinding breathing coldhot plane.

It was the counter-picture of immediately earlier experiences. The blue sky had been a symbol of terror in the aerial war. It had meant flying weather, attacks by low-diving fighter planes and bombardments. As gunner at a four-barrel flak, surrounded by detonations, at night I used to see tracers draw their lines, hectically beautiful. But fear came before beauty; seeing was aiming.

The anonymous war force is smugly undisturbed by the fascinating pictures its activity creates. The exploding atom bomb would be the most perfect kinetic sculpture, could we observe it without trembling. Fright inspires inventiveness and gives birth to giant monsters. How big is art? How small is art?

I am sitting inside a peaceful eastbound jet. Outside the sun is rising, more beautiful than ever, in all colors ever seen and dreamt of and in all colors never seen nor dreamt of. New York has been great and hot, the sun lavish. Then the airliner dives into clouds and lands at Cologne: cold rain and gray light, all colors seeming to contain black. How many light artists have there been in Germany since Grünewald and Caspar David Friedrich?

When the German economic reconstruction took shape, and the comforters became so soft that they deserved to be called the world's softest comforters, the recognized intelligentsia expressed its embarrassment about this deaf and dumb luxury by singing ballads of decay and writing poems on the beauty of dying, memento mori of delightful disintegration. The how and the procedure were declared to be the contents. This did not disturb the clean meagerness of the facades behind which an archaic computer society was busily working. Any stagnating culture, any unimaginative policy cling to the status quo and discriminate against positive ideas. Content is regarded as suspect, positive content is nervously presumed by the manneristic society to be fascistic. Who wishes development and spiritual renewal in a country whose government party periodically wins the elections with the slogan "no experiments?"

There were two conventional possibilities: on the one hand, the pragmatic, technology-happy behavior of the obedient consumer; on the other hand, the critical resignation and poetic melancholy of the mundane and the nature addict. There was a third, uncomfortable possibility: a new beginning with a minute fraction of hope despite the catastrophic past, a faint yes, absurd optimism. And independent from national considerations: is there anywhere a synthesis of the technological, urban world and the world of natural forces? Must these preclude each other or might we trust in the fact that the sun makes roses grow and, at the same time, feeds power stations? That fire broils steaks and propels rockets?

Simon Rodia built the Watts towers. Asked his motives, he said: "I wanted to do something." When I felt halfway adult after nine years of studying, I started night exhibitions at my studio. I wanted to do something. From this Group Zero developed. Heinz Mack, Zero's cofounder, has been my friend, companion, rival and communicant ever since 1950. The night exhibitions started in April 1957. A year later we published the ZERO 1 catalogue-magazine (The Red Picture) and ZERO 2 (Vibration). During the summer of 1961, ZERO 3 (Dynamo), a longer document, came out. It contained picture and text contributions on the forces space, time, motion, calm, order, sensitivity, expansion, nature, light and hope. The night exhibitions were one-evening affairs. It turns out that they were analogous to Happenings, and they were discontinued as soon as galleries, such as the Galerie Schmela in Düsseldorf, opened and took the initiative.

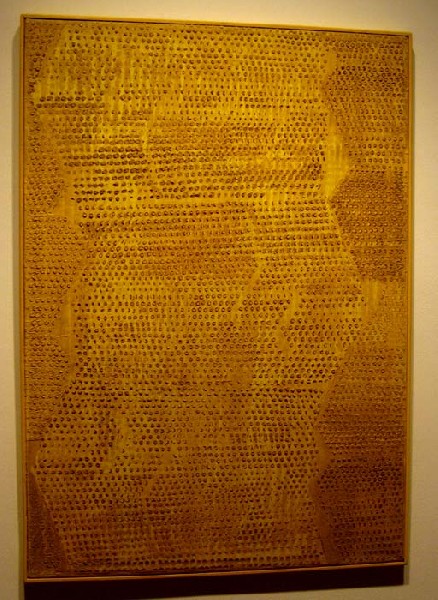

Beginning in September 1957. I showed stencil paintings involving relief points, which caught the light and put the picture surface in vibration. These had titles such as "whitewhite," "yellowyellow," and "pure light."

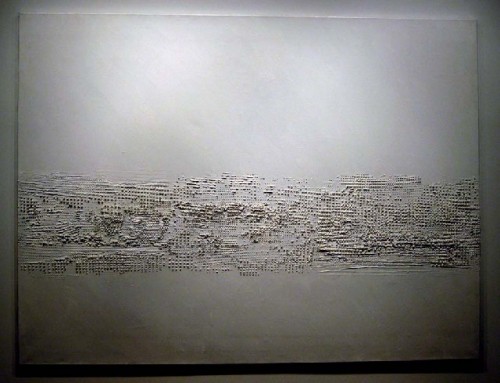

The stencil paintings became smoke paintings when I started to apply soot to the canvas through stencil sieves. The titles: "First Attempt to Burn the Night," "Second Attempt to Burn the Night," and so on, up to the "27th Attempt to Burn the Night." These paintings which employed smoke particles to produce images of vibration later developed into works with one single pulsating plasmation — the "Black Sun," the "Venus of Willendorf," and others.

Images of the sun turned into afterimages of the sun, a fire dance on the retina and a choreography of fire on the canvas. I ignited solvent that otherwise would have dried into an existence of gemutlich contemplation, and pictures grew within seconds on a border line between destruction and survival — the "Fire Flowers." To me they were a liberation from the rules of optical exploitation of geometry and a turning towards organic forms which derive from melting and technological processes.

When, now and today, art communicates, it is not so much a transmitter of ideas and information as it is a sender of energy. How the visually transmitted energy changes into a spectator's emotional energy remains a secret. Certainly the dosage plays a part. The real sun burns and singes; an artistic synonym of the sun can calm and heal. Calm and quietness define the climate of the light ballet.

At first I used hand-operated lamps whose light I directed through the stencils I had used for the stencil paintings. Controlled by my hands, the light appeared in manifold projections around the entire rooms — that is, not only on a limited plane such as a movie screen or standard stage. The light choreography was determined by jazz or by an accompanying sound, which I produced myself.

The solo turned into a group performance, with each member of the ensemble holding individual lamps and contributing different shapes and colors to the overall rhythm of the projection. Feelings of tranquility, suspension of normal balance and an increased sensation of space were reactions that viewers volunteered to me after finding themselves in the center of the event. That their everyday fearful nervosity diminished was a sensual effect that I welcomed.

The light ballet lost spontaneity and gained steadiness when I mechanized it. Motors caused the steady flow of unfurling and dimming, reappearing and vanishing light forms, which metaphorically described the continuous change from day to night. A light ballet continues as long as one likes. He who wants it switches it on. He who has had enough switches it off. I like the possibility that it may last, without beginning and without end.

In 1959 I played the light ballet with hand lamps, in 1960 I built the first machines, in 1961 they appeared in large darkened rooms at exhibits and in museums: one object, two objects in a large hall, a waste of space, an elimination of conventional attitudes about quantity. The farther the distance between the projecting device and the light-catching confines of a room, the larger are the light forms. And when they are large, the claustrophobia caused by the ordinary cubicity of our interior spaces recedes. In 1962, at my suggestion, Heinz Mack, Günther Uecker and I set up the first "salon de lumière" at the exhibit "nul" at the Stedelijk Museum in Amsterdam. The salon consisted of a group of automatically programmed projecting and reflecting objects, light sculptures in the active as well as passive sense. Many variations of the light salon, such as my "Permanentes Lichttheater" in the "nul 1965" show at the Stedelijk, followed in changing constellations.

My endeavor is twofold: to demonstrate that light is a source of life which has to be constantly rediscovered, and to show expansion as a phenomenal event. Everything is striving for larger space. We want to reach the sky. We want to exhibit in the sky, not in order to establish there a new art world, but rather to enter new space peacefully — that is, freely, playfully and actively, not as slaves of war technology.

A rubber skin, helium and the wind, light, electricity and fireworks seem to me excellent media. The revolving beam of a lighthouse and a balloon in the air are more convincing sculptures than the big chunks that are so hard to move. Calder's mobiles can be taken apart. Our objects ought to be inflated or ignited or projected. And environments? As far as a laser beam reaches. Are the jet pilots who write vapor trails in the sky the artists of our time, as Gothic stone-masons were the artists of theirs?

Despite their similar shapes, there is one essential difference between Gothic cathedrals and rockets: a cathedral seems to soar, expressing the yearning of its builders to ascend to heaven; a rocket does soar. The same technical difference exists between traditional sculpture and my objects. Previously paintings and sculptures seemed to glow, today they do glow, they are active, they give, they do not merely attract the eyes, they do not merely express something, they are something. A filament glows and warms, a painted halo only reflects light. Energy in a contemporary form produces the living media. Is the filament in itself a piece of art?

Transformation still has two meanings, one technical, one spiritual. He who leaves his house leaves the light on to make it appear inhabited.

- Otto Piene