Setting the Stage for Another Halo Lost

Early 20th C. Modernism, Surrealism Challenge Established Art Protocols

By: Richard Friswell - Apr 22, 2013

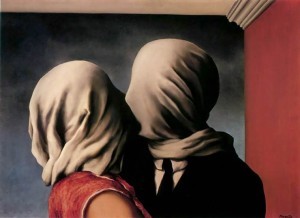

Loss of a Halo

By Charles Baudelaire

From, "le spleen le Paris: petits poèms en prose" (1863)

“Eh! What! You here, my dear? You in a place of ill-repute! You, the drinker of quintessences! You the eater of ambrosia! Indeed, this really surprises me.”

“– My dear, you know my terror of horses and of carriages. Just a little while ago, as I was crossing the boulevard very hastily and jumping about in the mud, through that moving chaos in which death comes galloping toward you from all sides at once, I moved abruptly and my halo slipped from my head into the mire on the pavement. I didn’t have the courage to pick it up. I decided that it would be less disagreeable to lose my insignia than to break my bones. And surely, I told myself, bad luck is always good for something. Now I can walk about incognito, commit base actions, and give myself over to filthy debauchery, like simple mortals. And here I am, just like you, as you can see!”

“– You should at least place a lost and found advertisement for that halo, or make a claim for it at the police station.”

“– By my faith! No. I’m quite comfortable here. You’re the only one who has recognized me. Anyway, dignity bores me. And I can’t help but feel joyful when I think that some bad poet will pick it up and impudently set it on his head. What a delight to make someone happy! And especially someone who will make me laugh! Just think if it were X, or Z! Hey! Wouldn’t that be funny!”

When Baudelaire’s poet abandoned his halo in the mire of a Paris street, he did more than disclaim the mantle of adoration affixed to those, like him, who had gone before ; he traded the sacred for the profane, embracing the intimate, familiar surroundings of a brothel in favor of the distant accolades of countless anonymous strangers.

Newly-modern Paris had razed the artifice of the past, and along with it, cast aside the historical foundations of classical historicism and sovereign autocracy that had bound it to its own tumultuous history. Europe in the closing years of the century was poised for another revolt—not at hastily-erected street barricades of the garde nationale—but in the studios and libraries of painters, playwrights and poets.

Sixty-seven years later, and a nation away, Dadaist/Surrealist painter, Max Ernst, produced his Virgin Mary Chastening the Christ Child before Three Witnesses: Andre Breton, Paul Eluard, and the Painter (“Spanking”), 1926. Considered a blasphemous send-up of the sacred, the scene was instantly recognizable as the centuries-old, classically-posed Virgin Mother and Christ Child motif—where the mother of purity has been traditionally shown offering succor and comfort to her divinely ordained son.

Here, conventions of faith are thrown out the window, as Ernst portrays the two main figures of Mary and Jesus in a landscape of Cubist-style pastel walls against a flat blue sky. The child has been laid on Mary’s lap to be reprimanded. Christ’s halo, like Baudelaire’s, has been dislodged and fallen to the ground. Denied his halo, the figure of the recalcitrant child is symbolically diminished as the Savior of Man, becoming just another child. Looking on, voyeuristically, is the artist himself, and two other identified founders of the Surrealist movement. While their facial expressions seem superficially non-committal, there is enough ambiguity in their rendering to suggest an empathetic connection to the scene. More broadly, the avant-garde community of artists of the time would likely bear witness to Ernst’s blatantly profane interpretation of this familiar motif—in light of a radical humeur des temps—as meeting with their approval.

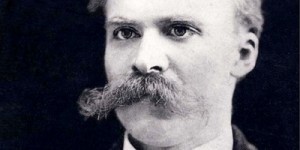

It is a somewhat artificial exercise (and does historicism no favors), to attempt to tease out just one of many influences that may have impacted on the production of this painting, by this artist at this time. But, for purposes of elucidating the writing of Friedrich Nietzsche and beginning to understand his contribution to the emergence of the avant-garde community of artists—and other iconoclasts redefining man’s relationship to the dogma of establishment religion and other social institutions—his writings are instructional. But, consistent with an ahistorical approach, Nietzsche might caution against excessive pondering of the past (“this antiquarian history”), with its accumulation of memory and tradition, encouraging an exploration of the “exercise of will” to reject (or at least re-evaluate) the values that place man is a state of “passive nihilism.” These entirely subjective beliefs render him oblivious to the philosophical and religious absolutes that then-modern society had evinced as obsolete or groundless.

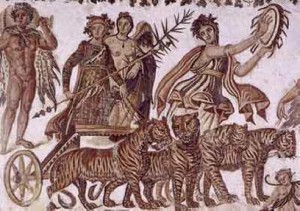

In Nietzsche’s writing, one finds the philosophical rationale for grappling with our self-centered existence. His early work, The Birth of Tragedy is influenced by Schopenhauer, in the form of Nietzsche’s characterization of purposelessness in the human condition and his view of reality as filtered through ordinary human consciousness. In his distinction between the Dionysian (passion) and Apllonian (controlling) elements in Greek arts and letters, it was the seamless dialogue between these two influences that lent vitality and Zeitgeist to the culture of that time.

Nietzsche postulates that the creative tension between these contravening forces (terror and ecstasy) was lost because of aristocratic decadence and a period of Socratic dialecticism and Platonic dualism that would reject passion completely. While widely panned at the time of its publication, because of his daring departure from the conventional wisdom of the time relating to the power and influence of Greek culture, Nietzsche later defended the work (Ecce Homo, 1888), by pointing out that the Dionysian phenomenon provides a root understanding of Greek art, in general; and that Socrates played an instrumental role in the disintegration of Greek tragedy by stressing “rationality over instinct.”

These last points—roots of passion in tragedy and Socratic Rationality—are key, in my view, to building a bridge between Nietzschean philology and the various manifestos forming the foundation of early 20th century avant-garde artistic movements—and more specifically, Ernst’s Spanking. What must have been ringing in the ears of artists and writers of the time—along with the compelling pronouncements of Freud, Hegel, Marx and others—were the later writings of Nietzsche, who addressed the rise of Enlightenment secularism by famously declaring, “God is dead.” By this, of course, he meant to debate the role of self as a conscious vehicle for interpreting the subjective experience of “being” in the world—the sensory-based source of all knowledge. He argued that consciousness (and its communicative vehicle, language) had been “absurdly overestimated,” as a cipher for interpreting experience and events. Values, beliefs and concepts, in this schema, all derive from a highly personalized connection to the world; that is, the experience of the “I” becomes, de facto, a schematic foundation for understanding the universal ordering of events around us.

In On Truth and Lies… (1873), Nietzsche notes, “That haughtiness which goes with knowledge and feeling, which shrouds the eyes and senses of man in a blinding fog, therefore deceives him about the value of existence by carrying in itself the most flattering evaluation of knowledge itself.” This egocentrism, he argued, is responsible for Christianity’s influence, with its emphasis on personal immortality, through which an individual’s life and death acquire cosmic significance. With the collapse of metaphysical and theological constructs of morality in a modern world, nihilism would triumph, with the resultant pursuit of surrogate gods to invest life with meaning. “if he does not wish to be satisfied with truth in the form of a tautology—that is, with empty shells—then he will forever buy illusions for truths.”

Enter, a generation later, Max Ernst and the avant-garde movement. Post-World War I Europe was an ideal spawning ground for a population of Germans, devoid of will and depleted of resources; they were now eager to embrace the promises of a nation-state, in lieu of the omniscient God who had abandoned their cause. Often standing in defiance of political mobilization characterizing much of the strife-torn Weimar Republic, were the German Expressionists, Dadaist and, by the mid-1920s,Surrealists. Max Ernst, one of many Dadaists-turned-Surrealists, embraced a variation on the Nietzschean view of questioning perceived societal norms, as they questioned the form of political and social absolutes.

Their actions elaborated on such questions, as those raised by Nietzsche, about the nature of received information—i.e. moral, political and aesthetic beliefs—that had been destroyed by the war. They advocated a destructive, irreverent and liberating approach to art (invoking Hegel, too, with his dialectic notion of sublation: intending to keep, to preserve, and at the same time to discontinue, to cease).

It was the intention of avant-garde art to go one step further, however: It was conceived to be an attack on the status of art in a bourgeois society, both as a mocking and restructuring gesture, so that it could be readily transferable to the praxis of everyday life, but in changed form. Their use of common, everyday materials, social commentary and oblique references to the unconscious were intended to offer a coded message to Jedermann—that life was forever altered and old rules were being relinquished in favor of a new aestheticism.

Spanking’s target message was aimed at these core themes. “Rebellious, heterogeneous, full of contradiction, [my work] is unacceptable to specialists of art, culture, morality. But it does have the ability to enchant my accomplices: poets, pataphysicians* and a few illiterates,” Ernst would later say. In this painting, we witness the encounter of the saintly and the profane. The mother-child motif refers quite deliberately to the Italian Madonna of the Renaissance and Mannerism. But, the Christ Child is manifestly human, with his cherubic body, curly blond hair and smarting hind quarters.

The heresy in this work can be seen at many different levels. The always staid and patient Mary has given in to her human emotions, venting her anger at the now humanized child, for some act of insubordination (original sin?). The child, corpulent and squirming, has his face turned away, as though to preserve dignity, although his pure nakedness belies the modesty usually attending representations of his often nearly-stripped body. The fallen halo, lost in the fracas, has tumbled to the ground. Ernst has quite nonchalantly painted his signature on the halo, relegating himself to the role of “X, Y or Z” in Baudelaire’s earlier story—symbolically placing it upon his own head in an “act of impudence…[and] humor.” Once again, the sacred is rendered profane in an act designed to rebuke the past.

*Pataphysics: the science of imaginary solutions, which symbolically attributes the properties of objects, described by their virtuality, to their lineaments.

Reposted from Artes Magazine courtesy of Richard Friswell.