Art In the Life of the City: Learning from London

A Symposium At The Harvard Design School Part 2

By: Mark Favermann - Apr 23, 2008

April 17 and 18, 2008At Piper Auditorium

The Graduate School of Design

Harvard University

Cambridge, MA

Organized by Camilla Ween, an architect/urban designer for Transport London. Ms. Ween is currently a Loeb Fellow at the Harvard Graduate School of Design.

Sponsored by the Loeb Fellowship Program

After a previous evening's keynote address by curator Claire Doherty that gave the audience a variety of visual tastes of ephemeral art in and around London and Europe, during the next day the Harvard Design School's symposium on Art in the Life of the City focused in-depth on specific projects and continuous programs in London. The day was filled with an abundance of artistic treats. The format was individual speakers presented followed by a moderated panel discussion and then a question and answer period by the audience. Not surprisingly, by an audience of artists and arts-oriented individuals, question time was often taken up by statements and occasionally personal manifestos.

The first session began by an illustrated presentation by Curator Claire Doherty focused upon various artist's projects. This presentation was followed by a film of the Waste Man project created in 2006 by British artist Antony Gormley in Margate, Kent. This documentary by Caroline Deeds was made following the building of Gromley's creation of a 25 meter high man constructed out of the detritus of contemporary consumer society. Director Deeds' film shows the relationship between this small seaside community and the building of a conceptual work of art by a prominent artist. Ms. Doherty questioned the patronizing tone of the film and also expressed that it misrepresented the Margate piece as part of the overall Exodus project. I agree with Ms. Doherty.

The documentary followed the difficulties of building the Waste Man involving Gormley's personal challenge of the very diverse community of Margate to work with a team of professional riggers. The artists wanted the residents who helped to make the Waste Man to feel a sense of ownership and to recognize it as an evocation of their own presence in the town. The artist felt that public art ownership underscored community unity.

Some saw the Waste Man as a waste of good wood and helped themselves to a pile of wood collected for the sculpture to supplement their own personal winter fuel, while others helping out with the sculpture represented a longed for some sort of wish-fulfillment for communal acceptance and belonging. The film followed the community's response to Gormley's aims even as they discovered that the Waste Man was to be burned to the ground upon completion. The film reveals the tensions inherent in a project so monumental that it is somehow beyond the personal experience of most involved, and suggests that the project evolves into a powerful symbol of community that many are sad actually to see go away.

Contrary to the almost wistful nature of the film , I felt that Waste Man was a derivative (aka known as a rip-off) project loosely based upon the American Burning Man, a project started by unreconstructed hippies in San Francisco during the Summer Solstice of 1986 and eventually transported to a desert location in Nevada. It is an annual 8 day festival/happening that culminates in burning a 40ft plus (15 meters) wooden man. The size of the festival grew from a few hundred in 1986 to over 47,000 participants in 2007. Documentaries and many articles have been done on it as well.

Another source may be the 1973 Scottish movie that was remade in 2006, The Wicker Man, that pitted murderous pagans against a Christian policeman and burned him in the belly of the wooden beast. Who knows? It doesn't seem very important, but originality should count for something. Or was it just a waste of time?

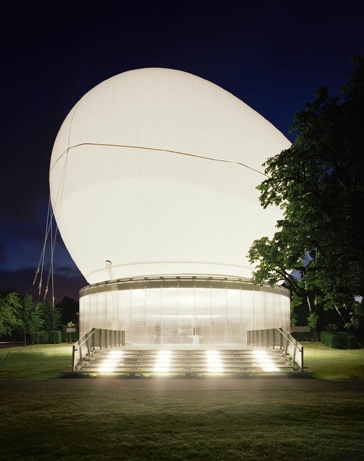

Perhaps the most elegant project presentation was by Julia Peyton-Jones, OBE, the Director of the Serpentine Gallery in Hyde Park since 1991 She has been responsible for both commissioning and showcasing groundbreaking exhibitions and public programs as well as the annual architecture commission, the Serpentine Gallery Pavilion. She conceived this concept.

Ms. Peyton-Jones carefully described the exciting Serpentine Gallery Pavilion Project that each year commissions an eminent architect to create a temporary pavilion. This is architecture as art object. The series of stunning pavilions are temporary structures built as permanent buildings, architectural jewels that literally disappear after four months.

The Serpentine Gallery Pavilion series, now entering its ninth year. It is the world's first and most ambitious temporary architectural structure commissioning program of its kind. These temporary pavilions have been part of the Serpentine's summer offerings since 1999. Past eminent architects include Zaha Hadid, Rem Koolhaus, Daniel Libeskind, Oscar Niemeyer and Toyo Ito. A few years later, the gallery began inviting both architects and artists to collaborate. Architect Rem Koolhaas first designed the pavilion while artist Thomas Demand created a decorative screen inside it. This was followed by Kjetil Thorsen, the Norwegian architect who co-founded Snøhetta, and Olafur Eliasson, the Danish installation artist. Each pavilion is a real building rather than a folly.

Every Serpentine pavilion is used for talks, events, and parties every week during summer months by hundreds of people at a time. They usually opens in June and close in September, are disassembled and sold off to help pay for themselves. The resale and recycling pays for about 40% of the project costs. Sponsorship and National Lottery money through the British Arts Council pay for the rest. In 2008, the Serpentine Gallery Pavilion will showcase for London the first example of Frank Gehry's architecture.

The prickly articulated structure comprises large timber planks and multiple glass planes that soar and swoop at different angles to create a dramatic multi-dimensional space. As with other architectural pieces of the series, the Gehry structure will be part-amphitheatre, part-promenade that will carry his quirky visual signature of seemingly random angles and element placement. As with other pavilions in the series, the building will be a place for reflection and relaxation by day, and discussion and performance by night.

Showing the design, construction and completion of each of the structures, Julia Peyton-Jones made a spectacular presentation of a fascinating and major project. Here, architecture became art. Even in a temporary way, the Serpentine Gallery has expanded the visual notion of the art institution and perhaps of architecture as well.

The most passionate speaker was clearly Michaela Crimmin. She is the Head of Arts at the Royal Society of Arts (RSA). Her career has focused strongly upon public art. She was a curator at Public Art Development Trust before directing Art for Architecture at the RSA and coordinating the first high profile series of sculpture for the Fourth Plinth. She is currently directing Arts & Ecology, a program linking art with the environmental and related social challenges and crises the world is presently facing. She is a Trustee for Channel 4's Big Art Project and a member of the Greater London Assembly's Fourth Plinth commissioning group. Michaela was recently elected to be a 'London Leader' by the London Sustainability Commission and the Greater London Assembly. One of her new projects is to establish an annual Arts & Ecology Day.

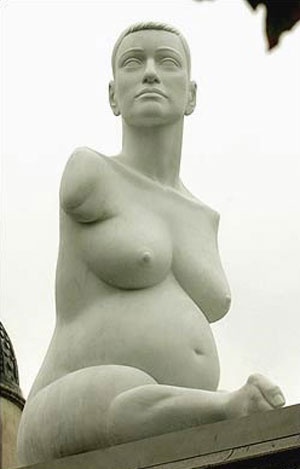

Ms. Crimmin first spoke about the fascinating commitment of various individuals, private organizations and public entities to the Fourth Plinth Project in Trafalgar Square. From 1841 until 1999 there was nothing on the Fourth Plinth in the northwest section of London's Trafalgar Square. Historically, it was sometimes referred to as the empty plinth, as it was the only one without a statue set on it. It is now the location for contemporary art works, commissioned specially from leading artists, which are housed on the plinth for about 18 months each.

Michaela spoke of the conceptualization of the pieces, their fabrication and their public exposure along with public reaction. By the way, the public reaction was considerably mixed, the comments ranged from highly positive to highly critical and individual members of the public actually felt ownership of the pieces of art. The pieces chosen for the Fourth Plinth have varied greatly in style, type and even quality. Ms. Crimmin was not critical in her presentation about the pieces, but she passionately made her point about the need for the project and the degree of community interest in each of the pieces. This is also true of the responses in regard to recent artistic submissions as well.

She saved her greatest passion for her newer interest in the area of what she refers to as ecology. She defines this term as anything dealing with the environment. Ms. Crimmins is fearful, actually scared to death, of the direction of our planet. Therefore, she wants to use the creative energy of the creative artists to teach, make people aware and demonstrate the problems of our environment.

She feels that art is a great conversation opener and that it provides a unique opportunity to explore the relationship between a variety of environmental issues and people. Her desire is to look at the really big issues such as conflict, migration, pollution, increasing populations and consumption, environmental degradation involving the artists' perspective and involving the cultural community in the sustainability of London and the world at large.

In 2005, Michaela Crimmin set up the Arts and Ecology program at the Royal Society for the Encouragement of the Arts, Manufacturers and Commerce (RSA), to be a catalyst for the insights, inspiration and imagination of artists in responding to global environmental challenges and their social costs. She passionately feels that society needs artists unique perspective on the enormous environmental challenges ahead.

The next speaker was Sheena Wagstaff, the Chief Curator at Tate Modern since 2001. She is responsible for creating and managing an extensive international program of major exhibitions and permanent collection displays as well as the massive Turbine Hall temporary commissions. In addition to planning the future program, she is currently working with the architects Herzog & de Meuron on the design of the new Tate Modern 2 extension. As a major curator at one of the most popular destination museums in the world (along with the Pompidou Centre in Paris and the Museum of Modern Art in NYC), Sheena Wagstaff is at once brave and creative. Over the last several years, she has developed a spectacular temporary and/or ephemeral commissioning program at the Tate Modern.

Sponsored by the Unilever Corporation, this annual commission invites an artist to make a work of art especially for Tate Modern's Turbine Hall. Commissioned artists were asked to stretch the boundaries of the gargantuan Turbine Hall's 500 foot long by 70 foot wide space. The space is so big that the City of London designates it as an enclosed street. The first artist to work in the space was Louise Bourgeois in 2000. Her installation consisted of three steel towers, entitled I Do, I Undo and I Redo. Visitors could climb staircases to platforms on the towers, which became stages for intimate and theatrical encounters between strangers and friends.

Another huge project was Marsyas, a work by Anish Kapoor. His sculpture for the Turbine Hall, comprised three steel rings joined together by a single span of PVC membrane. The piece was gigantic. In The Weather Project during 2003 and 2004, Olafur Eliasson toke this ubiquitous subject as the basis for exploring ideas about experience, mediation and representation. He created an actual sun representation. According to Ms. Wagstaff, this piece was interactive in surprising ways with the public. Smaller versions of his work are now being exhibited at the Museum of Modern Art.

In 2005-06, the 1993 Turner Prize winner Rachel Whiteread created a gigantic labyrinth-like structure entitled Embankment, comprising 14,000 casts of the inside of different boxes, stacked together and piled high to occupy the huge space. Artist Carsten Höller, dealt with the experience of sliding in slides that are impressive sculptures in their own right. What interests Höller, however, is both the visual spectacle of watching people sliding and the inner spectacle experienced by the sliders themselves. This took place in 2006-07. A much smaller version was set in place at the former ICA building in Boston several years ago.

The most recent temporary commission was spectacularly different. Rather than fill the Turbine Hall with a conventional sculpture or installation, artist Doris Salcedo created Shibboleth, a subterranean chasm that stretched the entire length of the space. It was sort of a cracking good time. Pun intended. I'll say it again: Sheena Wagstaff has been quite creative and institutionally brave. The major sponsor Unilever should get a lot of credit as well with the budget each year around half a million pounds ($1million).

The final presentation was by Helen Marriage, the Director of Artichoke, a non-profit organization that is involved in bringing events to the masses. She presented the Sultan's Elephant project of which she was the producer. She was the only speaker not to be institutionally-based or a true curator. In other words, she works on a high trapeze flying without a net. Interestingly, she considers herself a producer, one who facilitates a creative performance.

Helen Marriage described the event that she wanted to get done in Central London, actually in the 800 meters that was the processional road from Windsor Place down Saint James Street to Piccadilly Circus. Unlike the other presentations, this was about a performance piece that was not like any of the others. There was a narrative, theatrical framework to it. This comes out of a theatrical street theatre tradition as opposed to a visual art one. That is not to say that the visual quality and imagination was not on a very high level. It was.

Ms. Marriage explained how she had to get from no to yes from the myriad of bureaucracies that weave their authority throughout Central London. The process took almost six years. She discussed how these people were the "they" that could be the barrier to achievement of a public goal. Perceptively, she pointed out that the "they" are not driven by rules and regulations necessarily but by often just fear of change or fear of the new. Also, all of the people were men as well. She had to make them less fearful and become part of us rather than they. In order to do this, she flew them all to France to Nantes to view a Royal de Luxe performance. Her story ends happily. The bureaucrats were smitten. Permissions were eventually granted. Instead of being adversaries, the bureaucrats became collaborators. The positive result was that it is estimated that over a million people saw the event.

The Sultan's Elephant was a public performance piece created by the Royal de Luxe Theatre Company, a group that began as a political street performance troop. The performance involved a huge moving mechanical elephant and other associated public art installations—a rocket, a giant little girl and a customized bus. In French it is called La visite du sultan des Indes sur son éléphant à voyager dans le temps (literally, "Visit From The Sultan Of The Indies On His Time-Traveling Elephant"). The elephant was made mostly of wood, and is operated by over ten puppeteers using a mixture of hydraulics and motorized armatures. It weighed 42 tons, as much as seven African elephants.

This event was absolutely exhilarating. It was a street performance spectacle for the ages that underscored everyone's fantasy, imagination and delight. The symposium's audience members were also delighted by the documentary of the 2006 event. Ms. Marriage's warm and personable committment to the project shone through her presentation.

Temporal and ephemeral art are nothing too radical or very new. This wonderful Harvard Graduate School of Design symposium demonstrated that the whole rich area of ephemeral art is now being considered seriously by art professionals and thoughtful funding sources in an expanding way in the UK and in Europe. There is much to learn from London. Now, if only similar attitudes could be transferred to the United States as well.

Showing the design, construction and completion of each of the structures, Julia Peyton-Jones made a spectacular presentation of a fascinating and major project. Here, architecture became art. Even in a temporary way, the Serpentine Gallery has expanded the visual notion of the art institution and perhaps of architecture as well.

The most passionate speaker was clearly Michaela Crimmin. She is the Head of Arts at the Royal Society of Arts (RSA). Her career has focused strongly upon public art. She was a curator at Public Art Development Trust before directing Art for Architecture at the RSA and coordinating the first high profile series of sculpture for the Fourth Plinth. She is currently directing Arts & Ecology, a program linking art with the environmental and related social challenges and crises the world is presently facing. She is a Trustee for Channel 4's Big Art Project and a member of the Greater London Assembly's Fourth Plinth commissioning group. Michaela was recently elected to be a 'London Leader' by the London Sustainability Commission and the Greater London Assembly. One of her new projects is to establish an annual Arts & Ecology Day.

Ms. Crimmin first spoke about the fascinating commitment of various individuals, private organizations and public entities to the Fourth Plinth Project in Trafalgar Square. From 1841 until 1999 there was nothing on the Fourth Plinth in the northwest section of London's Trafalgar Square. Historically, it was sometimes referred to as the empty plinth, as it was the only one without a statue set on it. It is now the location for contemporary art works, commissioned specially from leading artists, which are housed on the plinth for about 18 months each.

Michaela spoke of the conceptualization of the pieces, their fabrication and their public exposure along with public reaction. By the way, the public reaction was considerably mixed, the comments ranged from highly positive to highly critical and individual members of the public actually felt ownership of the pieces of art. The pieces chosen for the Fourth Plinth have varied greatly in style, type and even quality. Ms. Crimmin was not critical in her presentation about the pieces, but she passionately made her point about the need for the project and the degree of community interest in each of the pieces. This is also true of the responses in regard to recent artistic submissions as well.

She saved her greatest passion for her newer interest in the area of what she refers to as ecology. She defines this term as anything dealing with the environment. Ms. Crimmins is fearful, actually scared to death, of the direction of our planet. Therefore, she wants to use the creative energy of the creative artists to teach, make people aware and demonstrate the problems of our environment.

She feels that art is a great conversation opener and that it provides a unique opportunity to explore the relationship between a variety of environmental issues and people. Her desire is to look at the really big issues such as conflict, migration, pollution, increasing populations and consumption, environmental degradation involving the artists' perspective and involving the cultural community in the sustainability of London and the world at large.

In 2005, Michaela Crimmin set up the Arts and Ecology program at the Royal Society for the Encouragement of the Arts, Manufacturers and Commerce (RSA), to be a catalyst for the insights, inspiration and imagination of artists in responding to global environmental challenges and their social costs. She passionately feels that society needs artists unique perspective on the enormous environmental challenges ahead.

The next speaker was Sheena Wagstaff, the Chief Curator at Tate Modern since 2001. She is responsible for creating and managing an extensive international program of major exhibitions and permanent collection displays as well as the massive Turbine Hall temporary commissions. In addition to planning the future program, she is currently working with the architects Herzog & de Meuron on the design of the new Tate Modern 2 extension. As a major curator at one of the most popular destination museums in the world (along with the Pompidou Centre in Paris and the Museum of Modern Art in NYC), Sheena Wagstaff is at once brave and creative. Over the last several years, she has developed a spectacular temporary and/or ephemeral commissioning program at the Tate Modern.

Sponsored by the Unilever Corporation, this annual commission invites an artist to make a work of art especially for Tate Modern's Turbine Hall. Commissioned artists were asked to stretch the boundaries of the gargantuan Turbine Hall's 500 foot long by 70 foot wide space. The space is so big that the City of London designates it as an enclosed street. The first artist to work in the space was Louise Bourgeois in 2000. Her installation consisted of three steel towers, entitled I Do, I Undo and I Redo. Visitors could climb staircases to platforms on the towers, which became stages for intimate and theatrical encounters between strangers and friends.

Another huge project was Marsyas, a work by Anish Kapoor. His sculpture for the Turbine Hall, comprised three steel rings joined together by a single span of PVC membrane. The piece was gigantic. In The Weather Project during 2003 and 2004, Olafur Eliasson toke this ubiquitous subject as the basis for exploring ideas about experience, mediation and representation. He created an actual sun representation. According to Ms. Wagstaff, this piece was interactive in surprising ways with the public. Smaller versions of his work are now being exhibited at the Museum of Modern Art.

In 2005-06, the 1993 Turner Prize winner Rachel Whiteread created a gigantic labyrinth-like structure entitled Embankment, comprising 14,000 casts of the inside of different boxes, stacked together and piled high to occupy the huge space. Artist Carsten Höller, dealt with the experience of sliding in slides that are impressive sculptures in their own right. What interests Höller, however, is both the visual spectacle of watching people sliding and the inner spectacle experienced by the sliders themselves. This took place in 2006-07. A much smaller version was set in place at the former ICA building in Boston several years ago.

The most recent temporary commission was spectacularly different. Rather than fill the Turbine Hall with a conventional sculpture or installation, artist Doris Salcedo created Shibboleth, a subterranean chasm that stretched the entire length of the space. It was sort of a cracking good time. Pun intended. I'll say it again: Sheena Wagstaff has been quite creative and institutionally brave. The major sponsor Unilever should get a lot of credit as well with the budget each year around half a million pounds ($1million).

The final presentation was by Helen Marriage, the Director of Artichoke, a non-profit organization that is involved in bringing events to the masses. She presented the Sultan's Elephant project of which she was the producer. She was the only speaker not to be institutionally-based or a true curator. In other words, she works on a high trapeze flying without a net. Interestingly, she considers herself a producer, one who facilitates a creative performance.

Helen Marriage described the event that she wanted to get done in Central London, actually in the 800 meters that was the processional road from Windsor Place down Saint James Street to Piccadilly Circus. Unlike the other presentations, this was about a performance piece that was not like any of the others. There was a narrative, theatrical framework to it. This comes out of a theatrical street theatre tradition as opposed to a visual art one. That is not to say that the visual quality and imagination was not on a very high level. It was.

Ms. Marriage explained how she had to get from no to yes from the myriad of bureaucracies that weave their authority throughout Central London. The process took almost six years. She discussed how these people were the "they" that could be the barrier to achievement of a public goal. Perceptively, she pointed out that the "they" are not driven by rules and regulations necessarily but by often just fear of change or fear of the new. Also, all of the people were men as well. She had to make them less fearful and become part of us rather than they. In order to do this, she flew them all to France to Nantes to view a Royal de Luxe performance. Her story ends happily. The bureaucrats were smitten. Permissions were eventually granted. Instead of being adversaries, the bureaucrats became collaborators. The positive result was that it is estimated that over a million people saw the event.

The Sultan's Elephant was a public performance piece created by the Royal de Luxe Theatre Company, a group that began as a political street performance troop. The performance involved a huge moving mechanical elephant and other associated public art installations—a rocket, a giant little girl and a customized bus. In French it is called La visite du sultan des Indes sur son éléphant à voyager dans le temps (literally, "Visit From The Sultan Of The Indies On His Time-Traveling Elephant"). The elephant was made mostly of wood, and is operated by over ten puppeteers using a mixture of hydraulics and motorized armatures. It weighed 42 tons, as much as seven African elephants.

This event was absolutely exhilarating. It was a street performance spectacle for the ages that underscored everyone's fantasy, imagination and delight. The symposium's audience members were also delighted by the documentary of the 2006 event. Ms. Marriage's warm and personable committment to the project shone through her presentation.

Temporal and ephemeral art are nothing too radical or very new. This wonderful Harvard Graduate School of Design symposium demonstrated that the whole rich area of ephemeral art is now being considered seriously by art professionals and thoughtful funding sources in an expanding way in the UK and in Europe. There is much to learn from London. Now, if only similar attitudes could be transferred to the United States as well.