Beckett in Boca Raton

Waiting for Godot at Sol Theatre Proves Powerful

By: Aaron Krause - Apr 24, 2017

With a Trumpian America in full swing, and the resulting uncertainty, fear and dread of many citizens, not just those of the U.S., perhaps it’s time to look at the much-analyzed and confounding “Waiting for Godot” through a dystopian, futuristic lens.

Seeing Samuel Beckett’s 1953 existential, absurdist masterpiece through such a prism is no doubt bleak and pessimistic. Then again, Beckett explores, among other things, futility in his play – a work that has probably left many foreheads bearing at least a drop of blood as critics and theatergoers scratched their heads in search of meaning and purpose in a work about a couple of tramps, well, searching for meaning and purpose in a universe seemingly devoid of them.

These thoughts came to mind during a recent performance of the current fine production of Beckett’s enigma of a play. It’s on-stage at Evening Star Productions’ extremely intimate Sol Theatre in Boca Raton, Fla. through May 7.

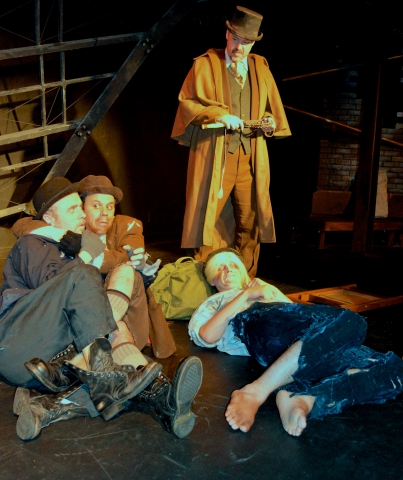

As you watch a superb Skye Whitcomb in the role of Pozzo command his slave with menace and glee like a Civil War-era slave master, it’s hard not to draw parallels to what many may fear will become of this country.

Set designer Ardean Landhuis’s dark, dreary landscape sets the scene for such a place – one in which people believe they’ve lost all purpose, usefulness and sense of time and place. The set suggests decay and deterioration, commonly found in Beckett’s work. In one spot stands a filthy brick wall sporting what looks like some sort of dried up yellow stain dripping down. The wall is cracked, the background is black and what resembles a ladder and a board is upside down, suggesting a topsy-turvy, disorderly universe. This production, however, could use some foreboding sound effects to further reinforce the darkness and dreariness.

If Christopher Mitchell’s ironically-named Lucky is anything resembling a person living in a future century, many living today might be glad they won’t be around to witness such a sight. Mitchell’s Lucky resembles a person, or perhaps a creature such as something out of Frankenstein’s lab, who hasn’t eaten, drank or bathed in months. He pants and snorts at such a rapid pace, you fear Mitchell, himself, will hyperventilate at any second. This “Lucky” man or creature can barely stand up, in stark contrast to Skye Whitcomb’s strong, commanding, ruthless Pozzo, whom we’re told is on his way to market to sell the pathetic being. Thoughts of an era of slavery repeating itself might repeatedly poke at our minds to the point that we feel rattled. Indeed, a March 3, 2017 Washington Times article reported that faculty at a university “mentioned student suicides (after Trump’s election) before requesting venues for quiet conversations and easy access to websites dedicated to preserving freedom.”

Yet for all the darkness inherent in Evening Star Productions’ “Waiting for Godot,” directed with sensitivity and an attention to detail by Rosalie Grant, laughter is audible throughout the audience. The contrast between lightness and darkness, hope and despair, with hope winning out at the end, is part of what has endeared so many to the play. Its multiple interpretations and layers of meaning was, no doubt, a factor in “Godot” being named one of the most significant plays of the 20th century.

The play made its debut in France in 1953 and had its American premiere at the Coconut Grove Playhouse in South Florida in 1956.

This “Godot” has many comedic moments, many of them coming courtesy of the deft physical comedy and verbal humor between tramps Vladimir (Lito Becerra) and Estragon (Seth Trucks). Just watching them, to borrow lyrics from “A Drowsy Chaperon,” “stumble, bumble, fumble, plumble” across the stage, jump on each other’s backs, wrestle with each other as well as with Pozzo and Lucky, represents the kind of slapstick, low comedy of the highest order here, that results in knee-jerk laughter. There’s a moment in the play when a suddenly vibrant and drill sergeant-like Pozzo gives way to a blubbering mess while a formerly piteous Lucky suddenly takes on the look of a ready-to-pounce, confident wild animal. The change happens so abruptly and seamlessly that it drew hearty laughs during the reviewed performance on Sunday. Our allegiances, too, suddenly and seamlessly shift from the slave to the master.

Of course, it’s hard to tell just who is who and what their purpose is in the plotless “Godot,” which leaves many questions unanswered and much fodder for discussion and thought. Who, for instance, is the mysterious boy (11-year-old Carsten Kjaerulff, demonstrating impressive naturalness even while nailing the youngster’s politeness and timidity). He claims to work for Godot. But how did he end up with the enigmatic being, or figure, or thing, or whatever? Are there two boys or one?

We know nothing about the background of the boy as well as that of Vladimir, Estragon, Pozzo and Lucky. The question on everybody’s mind is, likely, who or what is Godot? Beckett has insisted that Godot isn’t God, yet one cannot help think otherwise, since the first three letters spell “God.”

But whoever or whatever Godot is or stands for, the name symbolizes hope. As lonely, lethargic, sad, and defeated Vladimir and Estragon appear, they always retain a sense of hope. That is never more evident in the production than when Vladimir and Estragon (a nebbish of a forlorn, shaking, fearful fellow, as played by Trucks) literally lean on each other, place their arms around each other and comfort each other whenever they’re about to give up. They are, forgive the cliché, each other’s rock. No matter how bleak their situation, Vladimir (as astutely played by Becerra, he’s the more optimistic, reassuring, vivacious and thoughtful/philosophical tramp) ensures that the two forge ahead and continue to believe Godot will, in fact, come.

But then there’s the waiting. What are they to do until then? That’s where all the jokes, physical comedy and games come in. The two men, Vladimir in particular as portrayed by Becerra, is quite resourceful when it comes to finding ways to pass the time. You only wish you had this Vladimir’s company when you were stuck in bed, sick with the flu for weeks, or in that blizzard, with the power out for weeks, and, in the play’s opening words spoken by Estragon, “nothing to be done.”

Becerra and Trucks demonstrate equal skill at conveying despair and delight with their silly antics, of which there are aplenty. Their deft comic timing is on display when, for example, they play a game of trying to one-up each other as they hurl insults. A rapid fire of exchanges dart out of their mouths, building toward a crescendo, when the last, most hurtful insult is hurled.

Vladimir: Moron!

Estragon: Vermin!

Vladimir: Abortion!

Estragon: Morpion!

Vladimir: Sewer-rat!

Estragon: Curate!

Vladimir: Cretin!

Estragon: Critic!

It’s easy to be critical of the state of today’s world and fearful of what the future holds. It may, indeed, resemble the decaying, hopeless universe depicted on the Sol Theatre stage. But Beckett seems to say that as long as we each have our “Godot” to hope for, and each other to lean on, living will be at least tolerable.