For The Love of the Music : The Club 47 Folk Revival

A film by Todd Kwait & Rob Stegman

By: David Wilson - Apr 25, 2012

Tuesday night, April 17th, we attended the premiere of For The Love of the Music: The Club 47 Folk Revival screened as part of the 2012 Boston International Film Festival.

For The Love of the Music: The Club 47 Folk Revival attempts to tell the story of the legendary Harvard Square coffeehouse and folk performance venue, Club 47, and its eventual successor, Club Passim over the period from 1958 to 1968.

An hour and 45 min should be plenty of time to provide a comprehensive telling of the club’s history and role in what some call the folk revival of the ‘50s and ‘60s. While watching,time flew by and the film ended long before I checked my watch or wanted it to be over.

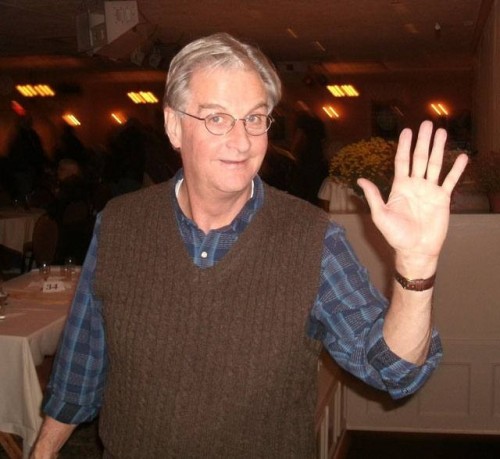

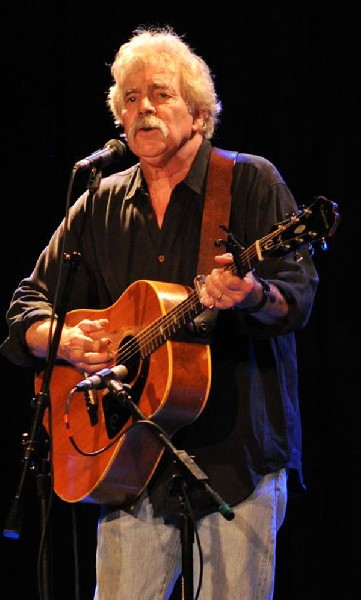

The film entertains. Interviews with Jim Kweskin, Joan Baez, Jim Rooney, Geoff Muldaur, Tom Rush, Peter Rowan, Jackie Washington and others were compelling, intimate and revealing although occasionally redundant.

One very significant factor for me is that most of the primary participants are musicians who began their careers as performers of traditional music and continue today to be so. They were and still are, competent, knowledgeable, creative and evangelical. In contrast, the industry in general has migrated to material content that is more transitory, the product of contemporary, acoustic singer/songwriters.

The framework of the film serves as support for several pertinent points. These include the appeal of music that was relevant to performers and audiences while corporate industry product was primarily irrelevant and vacuous. It highlights the fertility of an environment in which musical discovery, challenge and cross pollination became the focus around which a community formed. This evoked a unity that coalesced around the defense and validation of a lifestyle with a changing cultural perspective.

Through the recollections of Jackie Washington, aka Jack Landron, who talks of his sense of isolation in a community which literally adored and lionized him, we get to experience a small portion of his uniquely complex progress through a treacherous social and psychological landscape. As a young, African-American entertainer playing in white, middle-class venues Washington had to thread his way through a milieu filled with contradictions.

There are acknowledgements and tributes to Betsy Siggins in her role as talent coordinator, nursemaid, promoter, historian, facilitator, preserver, den mother and general dogsbody. The focus on her proves to be the story that binds the film together for me. Ironically, Betsy played that role, and still does, not only for a period in the ‘60s, but for longer and doubtlessly with less reward for much of the ‘90s and continuing to the present.

If you have any connection to folk music, and the decade of the ‘60s, this is a wondrous experience of nostalgia, seductive and charming. If, however, you come new or lately to it, the film provides an introduction, incomplete as it might be, to the times and the musical landscape of that scene.

For The Love of the Music: The Club 47 Folk Revival does not, however, fulfill or support the intention to which it seems to lay claim. Despite all the appreciations noted above, there are huge gaps in the content. There is much that leaves me shaking my head and wondering about the vision of the writers, directors and producers of the film.

Here are a few reasons why I wonder.

Although it sketches the events of a decade, the participants and events upon which it primarily focuses were present and central to the scene scarcely a third of that time.

It totally ignores or barely refers to a number of participants who were crucial to the Club 47 milieu including Rolf Cahn, who was second only to Eric Von Schmidt in musical influence in that community during that period. It does not acknowledge the seminal contributions of Bill Wood, Ted Alevizos, Robert L. Jones, Mitch Greenhill, The Geissners, Dick & Mimi Farina, Dayle Stanley, Zola, Paul Rothschild and any number of others. It gives scant mention of the contributions of Manny Greenhill other than his role as Joan Baez’s manager.

The film never mentions that much of the repression brought down on the club was the result of hosting a benefit for SANE, also known as The National Committee For A Sane Nuclear Policy. It fails to acknowledge that in its time of crisis, many of the other folk clubs in the metro area came to the aid of Club 47, with benefits, offers of physical assistance, promotion and public support.

In fact, if you did not know better, from this film you would think that Club 47 not only invented the folk scene but was its sole embodiment. This creates the impression that the performance venue was solely responsible for the rise of folk music’s popularity in its area if not nationally.

Of the dozen or more other clubs that existed in an era that contributed to a dynamic and fertile medium for the music and its adherents, only one, The Unicorn, got a brief though dismissive reference.

Not even Tulla’s, two blocks away from the club and one of the first venues to provide Baez with a stage gets mentioned. Important venues deleted from this narrative include; The Golden Vanity, The Boston Folk Song Society, Old Joe Clark’s, Eliot House’s American Music concert series, and WGBH’s “Folk Music USA.” While Tom Rush’s Balladeers show on Harvard’s WHRB gets a nod, MIT’s extensive and ambitious forays into folk go without mention. Yet, I would suggest, all of them were essential contributors to the vitality and survival of Club 47.

The film does acknowledge the tendency of the Club 47 core to cliquishness via the comments from out of area performers, Judy Collins and Carolyn Hester. But this is rebutted with a shrug and an “it’s not what we intended, but it might have seemed that way…” disclaimer.

The only two historians and documenters recorded are Scott Alarik, and Elijah Wald. They are both recognized for their contributions to genre history, but neither of them was around during the period concerned. With minimal effort, relevant and more knowledgeable sources could have been uncovered.

The addition to the film of several younger, contemporary musicians mystifies me completely. It seems incongruous and distracting.

In conclusion, while I loved and enjoyed most of what this film offered, I am disappointed at its failure to frame its content realistically. It chose to pluck the low hanging and fallen fruit from a fertile orchard at the expense of a wider and more authentic bounty.

Knowledgeable students will compare “For The Love Of The Music” with an earlier documentary, ”Rockin’ At The Red Dog” which chronicles a seminal period in the west coast development of Psychedelic Rock. The structure of both films is similar. Not having been active in the latter arena, I cannot vouch for its adherence to reality, though it seems to have relied on a greater number of sources who participated in events than on contemporary analysts looking back.

Having said all that, I think that many of our readers will find a lot to enjoy in the film, as did I. One would hope that, as I do, they will also look forward to the possibility that someday, someone will do a more thorough, less myopic cinematic treatment of what was an incredible period of musical restoration, recreation and realization. It would recognize the central role of Club 47 without ignoring so completely the contributions and participation of a much broader community of musicians, venues, devotees and culturally diverse elements than are portrayed in this film.

As of this moment, the next screening of this film will be at the Brattle Theatre in Harvard Square on Wed, May 30th.