Bauhaus Centennial a Global Celebration

Numerous Exhibitions and Publications

By: Charles Giuliano - Apr 25, 2019

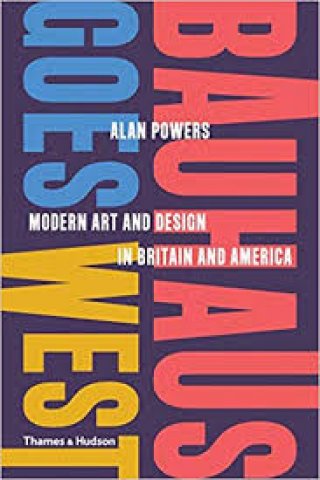

Bauhaus Goes West; Modern Art and Design in Britain and America

By Alan Powers

280 Pages, illustrated, with endnotes, index and bibliography

Thames and Hudson, New York, 2019

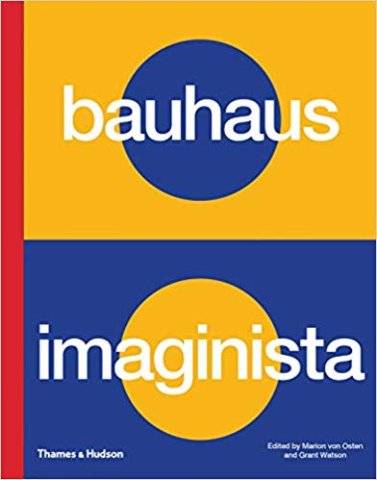

Bauhaus Imaginista

Edited by Marion von Osten and Grant Watson

312 pages, illustrated, endnotes, and notes on contributors

Thames and Hudson, New York,

Josef Albers Life and Work

By Charles Darwent

350 pages, illustrated with endnotes, index and bibliography

Thames and Hudson, New York, 2018

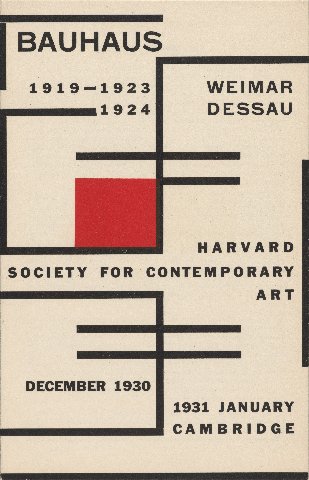

The first international Bauhaus show was held at The Indian Society of Oriental Art in Calcutta in December, 1922. For “The Bauhaus in Paris,” founder Walter Gropius enlisted Herbert Bayer, Lazlo Moholy-Nagy and Marcel Breuer to curate the German entry to the Society of Decorative Artists’ annual exhibition, in 1930. The Harvard Society of Contemporary Art mounted a Bauhaus exhibition in December, 1930. In 1931 there was a Bauhaus themed exhibition in Japan. In 1938, MoMA had its first comprehensive Bauhaus exhibit. Entitled "Bauhaus, 1919-1928," organized by Gropius and designed by Herbert Bayer.

This international exposure proved to be seminal when the NAZIs closed the Berlin Bauhaus, after just a semester. Over 14 years in Weinmar, Dessau, and Berlin the utopian, fraught, experiment to integrate art, design and architecture as a workshop, collaborative tradition continues to inform and inspire.

Those early exhibitions proved crucial in providing exposure that led to commissions and faculty appointments in the United Kingdom, U.S.S.R., and the United States when Bauhaus faculty and students fled The Third Reich. After a 36-hour interrogation by the Gestapo, Ludwig Mies van de Rohe, was able to negotiate a non violent closing of the school. That also entailed safe passage for the few who remained in Germany.

The dissemination of the Bauhaus inspired International Style of architecture and collaborative, workshop/ craft oriented pedagogy is the subject of “Bauhaus Goes West; Modern Art and Design in Britain and America” by Alan Powers. Also from Thames and Hudson is a handsomely designed, elaborately illustrated book with numerous contributors expressing its inspirational globalism “Bauhaus Imaginista.” The handsome publication's numerous, brief, chapters/ vignettes have been skillfully orchestrated by Marion von Osten and Grant Watson.

Previously, we reviewed the superb “Josef Albers Life and Work” by Charles Darwent. From Germany, he and the weaver, Anni Albers, under the recommendation of Philip Johnson, joined then new Black Mountain College. When that experiment foundered Albers took over Yale's School of Art and Design. While Anni taught at the Bauhaus and Black Mountain she was denied a faculty position at Yale. At the time women were restricted from architecutre classes in the graduate program. Yale had no female undergraduates.

These books, published on the occasion of the centennial, reveal a complex history of interfaculty feuds, cabals, affairs and raucous costumed celebrations. Considering the machine like precision, glass and steel slab monoliths and streamlined designs, the history of the most famous 20th century art school is dauntingly complex and messy.

There is a photograph of the faculty with its famous professors and one female Gunta Stölzl . In addition to architects, Walter Gropius, Mies Van de Rohe, and designer/ architect, Marcel Breuer, Lazlo Moholy Nagy, a photographer and designer ran the metal shop. There were artists, Wassily Kandinsky, Johannes Itten, Paul Klee, Oskar Schlemmer, Lyonel Charles Feininger, Herbert Beyer, Xanti Schwasinki and Gyorgy Kepes.

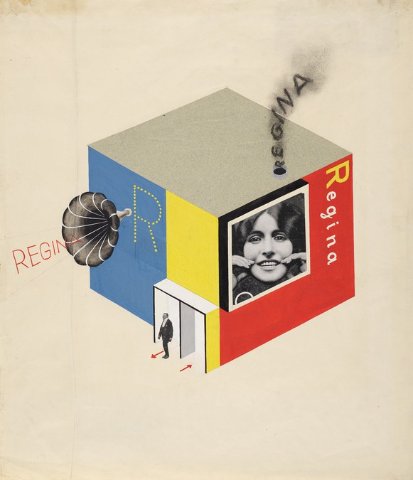

Women were discouraged or assigned to craft workshops. The contributions of Bauhaus women faculty and students are a focus of current research. They include Gunta Stölzl and Anni Albers in textiles; Lotte Stam-Beese in architecture; and Ré Soupault in fashion design, photography and journalism. The novel “Blaupause” (“Blueprint”) by Theresia Enzensberger focuses on a female student at the Bauhaus who wants to be an architect.

In April 1919, Gropius published a manifesto and program for the school: “The ultimate aim of all artistic activity is building!” he wrote. “The ultimate, if distant, aim of the Bauhaus is the unified work of art.” The title page of the pamphlet by Feininger and text by Gropius are reproduced in “Bauhaus Imaginista.”

The pamphlet was widely distributed to advertise a new school and sent to prospective students. Gropius retrofitted the Grand-Ducal Saxon School of Arts and Crafts into what he dubbed Bauhaus. Mies would later describe the word as the greatest contribution of Gropius. With brilliant brevity it signified the program. It served as a verbal logo for a very complex agenda.

Internally there was dissent. The influential early designer of the curriculum, Itten, was a cultist who also imposed a vegan diet. The wife of Gropius, Alma Mahler, noted his followers for their foul garlic breath.

There is controversy about the form follows function paradigms of Bauhaus. There is debate about its utilitarian design of quotidian objects from lamps to furniture and chess sets. The concept was to bring mass produced functional objects to market at affordable prices. That was not always the case. The mantra that less is more has morphed into less is a bore.

While Bauhaus elimited the ornamentation of Beaux Arts ultimately its stripped down aesthetic came to be regarded as cold and mechanical.

The Mies design for the 1929 Barcelona Pavilion is a case in point. While starkly minimalist in design it employed exotic and expensive materials. The critique that Bauhaus was too expensive for workers was the position of Hannes Meyer, a Marxist, who was director of the school from 1928 to 1930. He departed for the Soviet Union but there were shortages of materials for his projects. Under Stalin modernist approaches were untenable and he decamped for Switzerland and then Mexico.

Bauhaus suffered political opposition.. When Dessau was among the first cities to embrace Fascism the state supported school was defunded. As an industrial city, Dessau was heavily bombed. Some of the original Bauhaus structures survived but endured neglect. They have now been restored and attract tourism.

What made Bauhaus unique was its foundation program or vorkurs. It was a revolutionary overhaul of the dominance of French École des Beaux-Arts. That was primarily a government academy intended to create fine artists, muralists and sculptors for public works. Instead artists and designers instructed students through medieval, artisan/ craft traditions. It was hands on training of the role of design in fabrication. There was an emphais on understanding and working with materials. In the Albers workshop that included found shards of glass to create decorative windows and mosaics.

The collaborative approach of Gropius was that architecture would be a Gesamtkunstwerk or total work of art. That’s what he brought to The Architects Collaborative (TAC) which a group of former Yale students asked him to join as a mentor and senior partner.

There were many collaborations between Gropius and designer/architect Marcel Breuer. Their personal and professional relationship ended not long after they taught at Harvard. Breuer in America is best known for his design for the Whitney Museum on Madison Avenue.

For the centennial there has been an enormous number of exhibitions. Some 600 have been organized in Germany. During a recent week in Boston we viewed a small exhibition at the Museum of Fine arts, primarily graphics and photography, and a large, ambitious project at the Harvard Art Museums. Its Busch Reisinger Museum has a collection of some 50,000 objects, 32,000 of which are catalogued on line. With rigor that was scaled back to a display of 200 pieces with an emphasis on The Graduate School of Design's approach to vorkurs. The material was donated by Gropius, faculty and students.

An interesting aspect of the Harvard show is the emphais on student design projects. Most spectacularly displayed are large works Gropius commissioned for his Law and Design School buildings. These include a large relief work by Arp and a proto Op Art painting, "Verdure," 1950, by the typographer, and graphic designer, Herbert Bayer.

The Powers book details the long and winding road that led Gropius from London to Cambridge. The focus of the 280 page book is primarily about frustrations finding work and teaching positions in Great Britain. On page 188 the scholarly book begins discussion of how the Bauhaus spirit came to Chicago, Cambridge, and Ashville, North Carolina.

Gropius and his wife left Germany in 1934. The alleged reason was a visit to Italy for a film propaganda festival. From there he escaped to Great Britain with the help of architect Maxwell Fry. They lived and worked in the artists' community associated with Herbert Read in Hampstead, London. He joined the Isokon group with Fry and others for three years before moving on to Cambridge.

The collaborations of Gropius and Fry reveal interesting modifications to suit British clients. Their projects included Impington Village College, near Cambridge, Village School, Popworth, Cambridgeshire and The Wood House, Shelbourne, Kent. They proposed a complex for Christ's College, Camridge.

In Great Britain, Powers describes the generally conservative traditions of art and design. It was not opportune for a German during a time between the wars. Moholy Nagy built projects with F.R.S. Yorks. Bayer had commissions for graphic design, photography and advertising. For better opportunties they emigrated to America.

These artists/ designers/ architects required sponsors and jobs in order to emigrate to America. The artist Feininger was invited to teach at Harvard in 1936 where Gropius joined him in 1937.

Moholy Nagy founded The New Bauhaus in Chicago in 1937. The venture soon exhausted initial funding and closed in 1938. With support of Walter Paepcke, the Chairman of the Container Corporation of America, Moholy Nagy founded the School of Design in Chicago. In 1944 it became the Institute of Design. In 1949 it would become a part of Illinois Institute of Technology, the first institution in the United States to offer a PhD in design.

Gyorgy Kepes, a fellow Hungarian, joined Moholy Nagy in Chicago but left when the school folded. He had several teaching positions including Harvard. In 1967 Kepes founded The Center for Advanced Visual Studies (CAVS) at MIT. It promoted the confluence of art/science/technology. He was followed at CAVS by the German, Group Zero artist Otto Piene.

Having overseen the closing of the Bauhaus Mies struggled to continue his career in Germany. In 1937 he came to America to oversee a residential commission in Wyoming. His status improved when he was appointed head of the department of architecture of the newly established Illinois Institute of Technology (IIT) in Chicago.

While Chicago was noted for developing the tall office building, or skyscraper, remarkably, Mies ignored that legacy. It is said that he drove to work each day by cab and rarely looked out the window.

There is interesting discussion by Powers of the relative success of the American careers of Mies, Gropius and Breuer. Overall, Mies enjoyed the greatest recognition in creating iconic masterpieces.

He designed the campus, including the renowned Crown Hall, at the Illinois Institute of Technology. In 1952 he designed McCormick House, Farnsworth House in Plano, Illinois, and Morris Greenwald house in Weston, Connecticut. He is best known for 860, 880 and 900-910 Lake Shore Drive, the Federal Plaza, and the IBM building in Chicago as well as the Seagram Building in New York.

The Mies approach of sleek, glass and steel, tall office buildings has fallen out of fashion. Critics and theorists as diverse a Charles Jenks and Tom Wolfe critiqued the International Style. An ironic undoing was its ubiquitous success. Bauhaus design was replaced by a return to eclectic approaches conflated as Post Modernism. The Gropius role in New York’s mongrel Pam Am Building, perched over Grand Central Station, has been particularly savaged. Darwent disusses the fate of a monumetal Albers glass mural which was a landmark for Grand Central commuters. It disappeared during renovation.

The house that Gropius built for himself in Lincoln, a suburb of Boston, is much admired. In 1950, the University commissioned Gropius to design the Harvard Graduate Center, the first modernist architectural complex on campus. With TAC there were a number of projects including schools and private homes. For a time the firm prospered but eventually went bankrupt.

As did, in a metaphorical sense, the legacy of Bauhaus in America. While its dominance came to an end, during this centennial year, there has been critical thinking and reconsideration. Significantly, there is considerable interest in tourism of Bauhaus monuments, primarily in Germany, but America as well. If you drive around Chicago, or Park Avenue in New York, be sure to roll down the window.