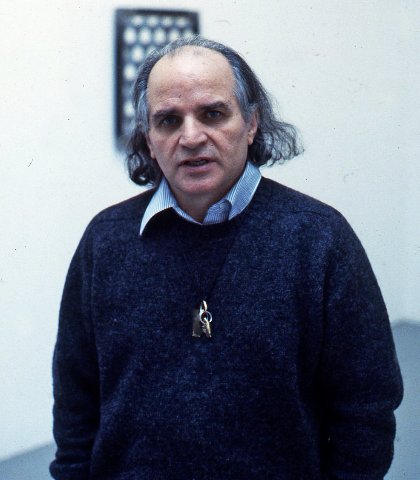

The Remarkable Mario Diacono

Opened a Boston Gallery in 1985

By: Charles Giuliano - Apr 26, 2020

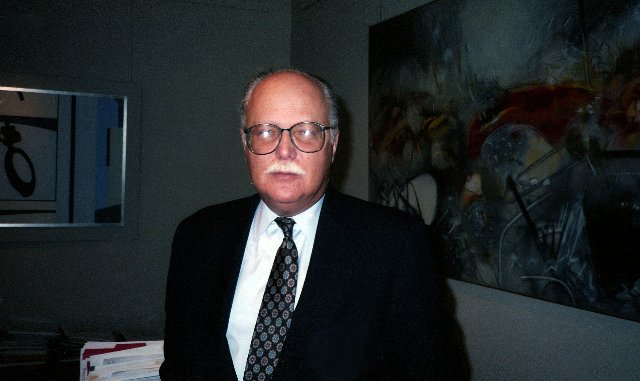

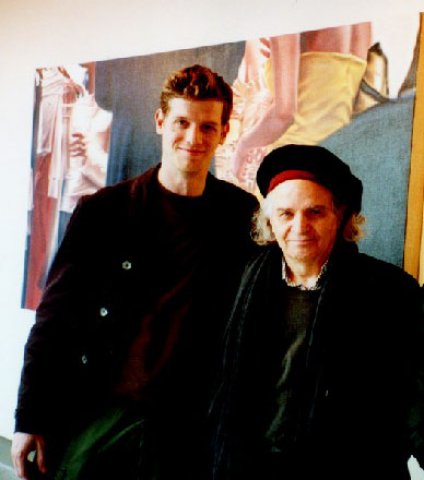

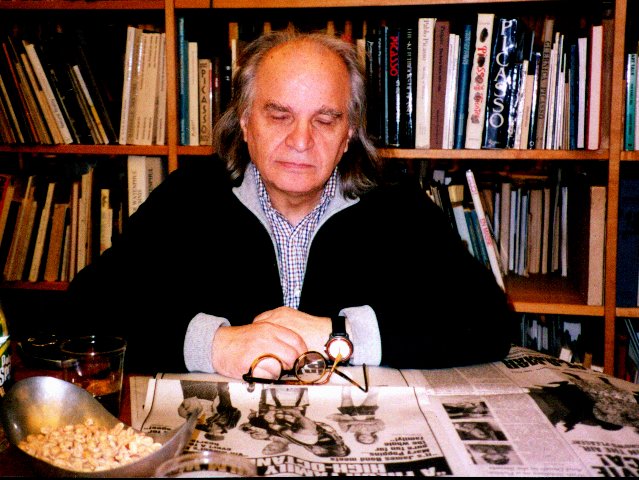

Born in Rome in 1930 the poet, essayist, and gallerist Mario Diacono, saw the Germans leave and allies arrive. With a degree in Italian literature he later taught at the University of California, Berkeley as well as Sarah Lawrence College.

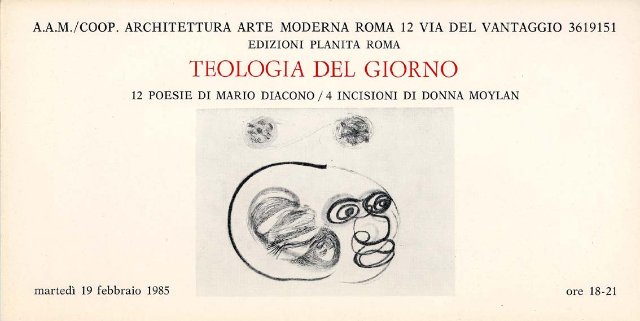

His first galleries were in Bologna and Rome. He initiated the format of showing a single work for which he was composing an essay. In 1985 he brought that approach to a gallery on Peterborough Street, in Boston’s Fenway area.

Diacono had exhibitions with some of the most renowned artists of his generation: Jean Michel Basquiat, David Salle, Francesco Clemente, Sandro Chia, Vito Acconci, Eric Fischl, Peter Halley, Ross Bleckner, Rosemarie Trockel, Roni Horn, Joseph Kosuth, Alex Katz, Julian Schnabel, Annette Lemieux and Damien Loeb.

There were other Boston venues on South Street and the wall of Ars Libri at 500 Harrison Avenue.

In the secondary market, works that he exhibited in some cases have sold for millions of dollars. The Basquiat, for example, brought $35 million at auction. For a Fischl painting that he sold for $17,000, there was an offer 20 years later from Fischl’s new gallery to buy it for $5 million. The collector said no dice.

While Boston collectors and curators visited the gallery, there were only a few sales. Two works were acquired by the Museum of Fine Arts and a couple by Dr. Bernardo Nadal-Ginard, whose collection was later impounded and sold at auction.

Most of the works were acquired by Achille Maramotti, the founder of the fashion house Max Mara. He continues to work for the Maramotti Collection as an informal curator.

Initially, Diacono came to Boston to be with his wife Claudette, who was then hospitalized. Her French-Canadian family is from Lynn.From 1985 to 2015 he traveled frequently to New York and Italy. Now he is quarantined in Brookline, leaving home to shop a couple of times per week.

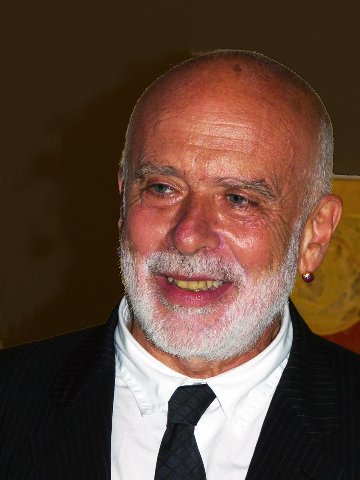

He has recently published the essays he wrote for Italian and American exhibitions in three books. His status in the art world is legendary.

Charles Giuliano Tell me about your Italian background.

Mario Diacono I was born in Rome in 1930. I earned a bachelor’s degree at the University of Rome in contemporary literature, writing a thesis on Futurism. After graduation I wrote for literary as well as art magazines, and art catalogues. That was between 1956 and 1966. In 1967 I moved to Milan and lived there for nine months, leaving in December.

I went to teach Italian literature at University of California, Berkeley. That lasted until the summer of 1970. My Fulbright grant was expired so I returned to Rome. There until 1972 I worked with artists and did some group performances, while working at the same time on collecting the essays of the poet Giuseppe Ungaretti.

CG You have war memories.

MD Yes. I was in a boarding school in June, 1940 when war was declared. There were alarms at night and we would be sent into the basement. When I heard the news of the war, I was with the kids watching a car racing. I was in the fourth year of elementary school. Soon after, the boarding school closed because of the war, I took an exam so the following year I went directly to middle school.

During the war I stayed home with my parents. September 1943 to June 1944 Rome was occupied by the Nazis.

CG I’m thinking of “Open City” (1945) by Roberto Rossellini.

MD Yes, it’s those years. The action of that film takes place in 1944 when I was 14-years-old.

CG Were you threatened to be drafted for the army?

MD No, because I was too young. My oldest brother was picked up in the street by the Nazis and sent to work in Germany. Near the end of the war he escaped from the labor camp and walked from Germany back to Rome, carrying in his backpack pretty much only a magnificent Russian icon which he had obtained who knows when and where.

CG We knew of that era through the great Italian filmmakers.

MD Rossellini was the main voice of that world. My second and third oldest brothers had to hide in the Vatican for nine months in order not to be taken by the Nazis. Once I was in the streets of Rome, on Via del Corso. Suddenly German and fascist trucks closed four or five blocks. They rounded up all the young men and put them on the trucks. I was fourteen and didn’t grab me. The men were probably sent to work in Germany, just like my oldest brother.

CG Do you recall the liberation of Rome?

MD Oh yes. My house was a block from the via Aurelia, where the first soldiers and tanks came through. It was the main route north and south. The day before I had seen thousands of German soldiers heading north.

CG Recently I have been having an argument with a colleague. He used the term “cute” to describe the work of Koons and other contemporary artists. I reminded him that there is an extensive bibliography of populism in the fine arts. That stimulated me to again read the seminal 1939 Clement Greenberg essay “Avant-Garde and Kitsch.” Given the time it was written, Greenberg had a lot to say about kitsch and fascism as a device for propaganda. Hitler, as a failed artist, embraced conservative classicism and the monumental but reactionary architecture of Albert Speer. His most inventive work, arguably, was the design of the Nuremberg Rally which was brilliantly documented in “Triumph of the Will” by Leni Riefenstahl.

By comparison Mussolini allowed more progressive design and architecture. Futurism and its celebration of the machine and dynamic movement was regarded as expressing the progress of Italian fascism. My understanding was that he was influenced by his Jewish mistress who was an art critic.

MD Until Mussolini embraced Nazi anti-Semitism he had a Jewish lover who was an important art writer. After 1937 she moved to Argentina. One of the closest friends of Mussolini was the poet Filippo Tommaso Marinetti, who was the head of Futurism. During fascism, futurist activities were allowed but primarily to praise Mussolini and his regime. An artist like Giorgio Morandi was able to work on his still life paintings, and wasn’t bothered by the fascists.

(Margherita Sarfatti, 8 April 1880 – 30 October 1961, was an Italian journalist, art critic, patron, collector, socialite, and prominent propaganda adviser of the National Fascist Party. She was Benito Mussolini's biographer as well as one of his mistresses.)

CG Is it fair to say that there was an iteration of the avant-garde in the art of Italian fascism, particularly in architecture?

MD There were great architects during fascism, like Terragni, but they were not great because they were fascists. The government allowed them to pursue what was a fusion of New Classicism and Rationalism. It’s not that the government allowed an avant-garde. Many Italian artists who had been in the avant-garde between 1910 and 1917 after WWI became fascists. They continued with their art but there was no real avant-garde.

(In the late nineteen-thirties, as Mussolini was preparing to host the 1942 World’s Fair, in Rome, he oversaw the construction of a new neighborhood, Esposizione Universale Roma, in the southwest of the city, to showcase Italy’s renewed imperial grandeur. The centerpiece of the district was the Palazzo della Civiltà Italiana, a sleek rectangular marvel with a façade of abstract arches and rows of neoclassical statues lining its base. In the end, the fair was cancelled because of the war, but the palazzo, known as the Square Colosseum, still stands in Rome today, its exterior engraved with a phrase from a Mussolini’s speech, in 1935, announcing the invasion of Ethiopia, in which he described Italians as “a people of poets, artists, heroes, saints, thinkers, scientists, navigators, and transmigrants.” The invasion resulted in war-crimes charges against the Italian government. The building is celebrated in Italy as a modernist icon. In 2004, the state recognized the palazzo as a site of “cultural interest.” In 2010, a partial restoration was completed, and five years later the fashion house Fendi moved its global headquarters there… The New Yorker, 2017)

CG Did you see the Futurism show at the Guggenheim? (2014, Italian Futurism, 1909–1944: Reconstructing the Universe)

MD It was a terrible show. It was presented as a futurist show, while eighty to ninety percent of the works in the show were created during fascism. It wasn’t the true futurism. It was futurism applied to fascist ideology. For me the exhibition was a scandal. In the US, they keep making the argument that futurism and fascism were the same thing. Which is totally bullshit. True futurism was active from 1909 to 1917. Fascism was born two years later, a consequence of the war. Marinetti and others soon became supportive of fascism. The curators of the Guggenheim show provoked again the confusion that futurism and fascism were the same thing, which is not true at all.

From 1910 to 1917 futurism was a movement just like cubism or German expressionism. It was purely an artistic and literary movement. It was very important for the rest of Europe, particularly the Russians.

CG Malevich.

MD Right, his early cubofuturist work, and was particularly influential for Russian poetry until the Russian Revolution. Afterwards, elements of futurism were very much present in the art and literature made in Russia between 1917 and 1924.

(Lenin died in 1924 and the Russian avant-garde was repressed when Stalin came to power. The dominant movement became social realism. Under Marxism-Leninism, art existed for purpose of agitation and propaganda, or agit-prop.)

CG When did you arrive in Boston?

MD May, 1985. I opened the gallery in December of that year.

CG Were you a gallerist prior to that?

MD Yes. My first gallery was in Bologna, 1978-1979. Then I had a gallery in Rome from 1980 to 1984.

CG You came to Boston because of your wife.

MD Yes. She was ill and in the hospital, so I came to be with her. She has a PhD in Italian literature from Columbia University. Claudette’s family is from Lynn, they were French Canadian. After she left the hospital, she wasn’t able to do much with her PhD and stayed home. She didn’t like to teach, so she went to Simmons College and took a degree in library science. Because of the crisis of the 1990 (Gulf) War, there were no jobs available; she is 16 years younger than I am.

CG What was the culture shock of moving from Rome to Boston?

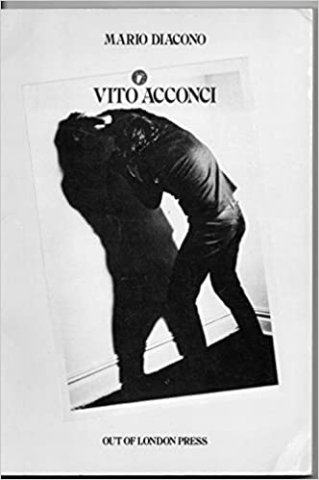

MD When I had the gallery in Bologna, I exhibited only Italian artists. I only did there an exhibition of Vito Acconci. In Rome I exhibited American artists; Julian Schnabel, David Salle, Joseph Kosuth, Jean Michel Basquiat, Eric Fischl.

CG How was that work received?

MD We forgot a stage before I opened my gallery. From 1972 to 1976 I came back to the US to teach at Sarah Lawrence College, but I had already met Acconci and Kosuth in 1969. During that time in New York, I met many other American artists, I wrote a monograph on Acconci, and became very familiar with the American scene. The real shock of Boston was how backward it was compared to New York.

The vitality of New York’s art world was made of three elements: The artists, the collectors, and the museums. In Boston, in 1985 there were almost no artists, collectors, or museums who were following what was happening in the contemporary art. I am not including the ICA , which was the only institution following the art of the moment. Especially the ICA of David Ross and Elizabeth Sussman.

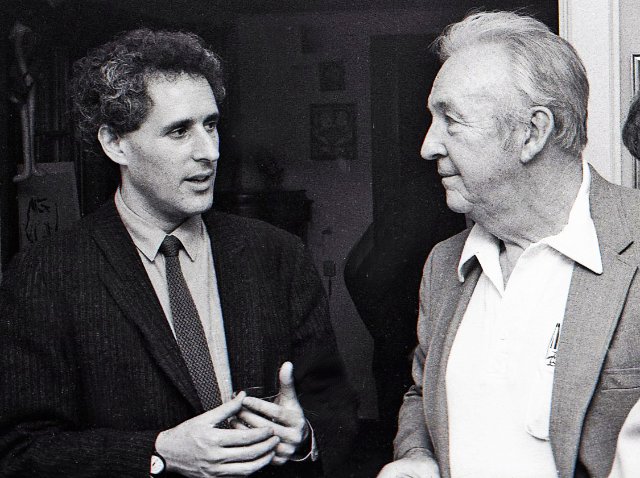

CG What was your relationship with David Ross? (ICA director from 1982 to 1990.)

MD We were kind of friends. I went to his exhibitions and he came to mine, but the relationship didn’t go much beyond that.

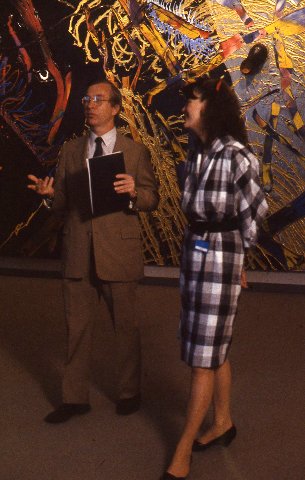

I had a stronger relationship with the Museum of Fine Arts for the first couple of years, when there was a curator of American art who had also become the curator of contemporary art, Ted Stebbins.

(Stebbins was a curator of American art who expanded his interests to contemporary art. He reported to Jan Fontein, who was MFA director from 1975 to 1988. Stebbins, and curator Amy Lighthill, in 1988-89 collaborated with the ICA and German museums on the multi-faced Binational exhibition.)

He was following closely the gallery, and bought for the museum a big Ross Bleckner painting in 1986. The museum also bought a work by Sherrie Levine, in, I believe, 1988.

My first show was a huge painting by Alex Katz. After him I showed Eric Fischl and Ross Bleckner. I showed later, twice David Salle, and once each time Julian Schnabel, Francesco Clemente, Sandro Chia, etc. I never sold any of those works in Boston.

CG Ever?

MD I sold those two works to the MFA. There was also a collector, Dr. Bernardo Nadal-Ginard, who bought an Enzo Cucchi and a Ross Bleckner. Later, it was said that he had cashed in advance his own pension; in any case, he went on to buy the best and newest artists in New York, and put together an important collection. The collection was later taken over by Harvard University and auctioned, making a very large amount of money. Afterwards he started a new life, and he is still a major collector.

(Widely regarded as Boston’s most ambitious contemporary collector, and potential donor to the ICA (which did not collect at that time, but might have) and MFA, he had in the 1990s legal issues. It was reported that “Boston cardiologist Dr. Bernardo Nadal-Ginard was handcuffed and led off to prison Monday after the state's highest court refused his final appeal of embezzlement convictions. Nadal-Ginard, former chief of cardiology at Children's Hospital in Boston, had been convicted in 1995 of embezzling more than $117,000 from the hospital and other groups. The state Supreme Court on Monday denied his request for further review. The heart doctor was convicted of 12 counts of larceny following a five-week trial in 1995, and sentenced to one year in the Suffolk County House of Correction in Boston.”)

CG Did Boston collectors come to the gallery?

MD Yes, but nobody bought anything. Graham Gund came often, but never bought anything.

CG Do you have any idea why that was?

MD I don’t. They collected mostly the older generation and were not much interested in the new work. But in truth I also sold at least a couple of works each to Marjory Jacobson, Dorothy Lavine, and Karen Meyeroff Sweet. They were important supporters of the gallery, especially in the years 1985-1990, before the market collapsed and I moved to New York. In those early years, they helped me a lot in getting acquainted with Boston’s cultural life, and have remained lifelong friends.

CG Stebbins also bought an Anselm Kiefer painting for the MFA. Did you have anything to do with that?

MD I had nothing to do with that.

CG The artists you showed are today all blue-chip artists. What you were asking then was cheap compared to the prices today.

MD We have to distinguish between 1985, when I showed Alex Katz, and 1990, when I showed Annette Lemieux. In those five years I sold most of the works outside of Boston. I sold all the Philip Taaffe paintings in my show, but not in Boston.

At the opening of the Philip Taaffe show, Alan Shestack (recently deceased former director of the MFA) stayed for an hour. He told me “I am waiting for Trevor Fairbrother (MFA curator) who is coming to decide if we want to buy a painting from you.” Trevor Fairbrother didn’t show up, Alan Shestack went away and never came back. I sold all the paintings to Switzerland.

CG What relationship did you have with Trevor?

MD We were quite friendly. I even made a “deal” with Trevor Fairbrother. In 1990, he told me, “Mario I would like you to make a donation of a work in my name to the MFA. It’s important to me if people make donations to the Museum’s collection.”

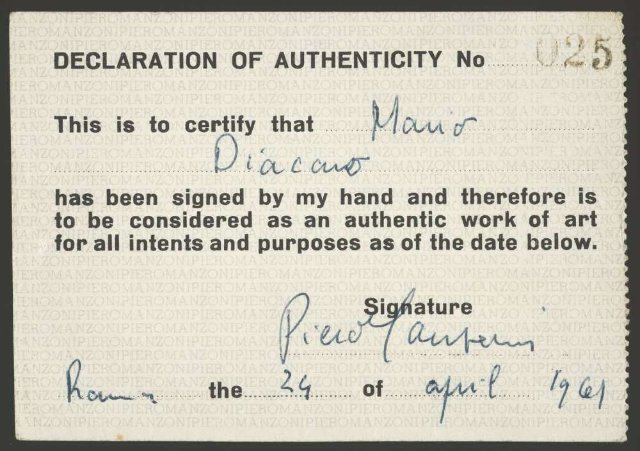

I gave to the museum my certificate of being a living art work by Piero Manzoni. Today it could be worth $100,000. I donated it, and didn’t even ask for a tax break.

CG Did you know Manzoni?

MD Oh yeah, I had met him at an opening in Italy. Before I met him, I had written an essay for a new magazine in Milan, in 1961. It was an essay on White in Contemporary Paintings, and it was about Fontana, Manzoni and Twombly. The new magazine never came out, and my essay was lost. So I met Manzoni at the opening of a show in Rome, and told him I had written this essay. He took out his sort of a check book, and wrote me the certificate of being a living art work.

(Manzoni, 1933-1963, was an early conceptual artist.)

CG Today how much are his cans of shit worth?

(In May, 1961 Manzoni created 90 small cans, sealed with the text Artist's Shit, Merda d'Artista. Each 30-gram can was priced by weight based on the current value of gold, around $1.12 a gram in 1960.] The contents of the cans remain a much-disputed enigma, since opening them would destroy the value of the artwork. Various theories about the contents have been proposed, including speculation that it is plaster. A tin was sold for € 124,000 at Sotheby's on May 23, 2007; in October 2008, tin 83 was offered for sale at Sotheby's with an estimate of £ 50–70,000. It sold for £97,250. On October 16, 2015, tin 54 was sold at Christies for £182,500.)

MD At the end of the ’80s, when I was following its market, it was about $30,000.

CG It would be an interesting conceptual piece to open a can of his shit and make a sandwich. Possibly it could be tuna fish. I wonder if a can has ever been opened.

MD I never heard about that.

CG Is there something in the cans or not?

MD Yeah, it’s supposed to be the shit of Piero Manzoni. That’s what he was saying to everybody.

CG As I understood, there was an Italian collector who would buy everything from you.

MD That was from 1978 to 2007, less however between 1985 and 1990. Then when I was closing the gallery in South Street because the market was completely dead, he started to buy again. My first gallery had been in Peterborough Street (in the Fenway), from December 1985 to Spring of 1990.

CG Did the Starn Twins (Doug and Mike) take over that space? ?

MD No, before it had been their studio. They were not paying the rent and were evicted, the owner then rented the space to me.

(Briefly the Starns had shown in that space which they dubbed Confusion/Order. I recall seeing work there by the artist/collector Randolfo Rocha.)

MD When I was closing that space and moving to South Street, as my last exhibition at Peterborough Street I asked the Starn Twins to do the last show. In my view it was their best show ever. They were quite large negatives of photographs, undulated, with an iron support. Most of the subject matter came from Greek classical sculpture. In the fall 1990, I opened the South Street gallery.

(In the leather district near Chinatown and South Station; there were also Robert Klein, Portia Harcus, Thomas Segal, and Howard Yezerski.)

When I opened the gallery in September, 1990 there was the Gulf War. Saddam Hussein invaded Kuwait, and the market collapsed. My first show was of Annette Lemieux, and I did not sell anything. Except to Achille Maramotti. From then on, I sold works from all my shows to him and they are now on view in Reggio Emilia. The collector, who was also a close friend, died in 2005 at 78.

(The Giulia Maramotti Foundation was named after the mother of Achille Maramotti, who was awarded the Title of Knight by The Order of Merit for Labour. The Foundation was established in 1994 with the aim of supporting, promoting and managing projects for young people in the education, training and cultural education sectors. Achille Maramotti, Italian fashion entrepreneur, born January 7, 1927, Reggio Emilia, Italy—died January 12, 2005, Albinea, Italy, founded the fashion house Max Mara and was credited with introducing high-quality ready-to-wear fashion to Italy. The Collection is now in the name of the family. It opened to the public in September 2007.)

CG How did you know him?

MD When I was teaching at Sarah Lawrence, from 1972 to 1976, each summer I would go to Italy for a month. In the summer of 1975, an artist friend of mine, Claudio Parmiggiani, introduced me to Mr. Maramotti. We spent a half a day together. In 1976, he came to New York for business and stayed for about ten days. We got together every day, I took him around to visit the galleries in Soho, and I introduced him to some of the owners of the galleries. We also visited all major museums in New York. A year later, when I had left Sarah Lawrence and was again in Rome, a friend of mine needed a lot of moneyto pay back taxes and had decided for this reason to sell three important paintings, two by Jannis Kounellis and one by Mario Schifano. Mr. Maramotti bought all three of them, and that started our collaboration.

CG Were there specific artists he asked you to acquire for him?

MD No. We always talked together about which artists to buy. When I met him, he was mostly collecting from the Scuola Metafisica period, Giorgio Di Chirico, Carla Carrà, Giorgio Morandi, those artists. But he also had a Burri, a Fontana, three Manzonis. When we became friends, we decided together that he would focus on collecting the artists of his own time, on putting together a collection of artists who were his contemporaries.

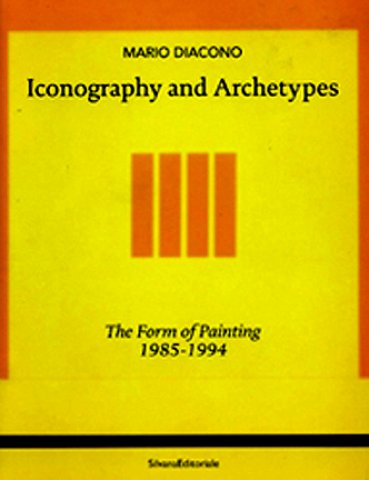

CG You were known, famous, or infamous for showing a single work by generally an advanced artist.

MD That’s what I was doing in Italy, first in Bologna then in Rome. That’s the way I started my gallery in Boston too, showing only one painting by Alex Katz. It was a twenty-two feet canvas, titled Twelve Hours.

For me the gallery was completely associated with my writing about art. Writing about one single painting or artwork allowed me to analyze in depth what the artist was doing, to make the connections to art history, etcetera. I have always showed an artist because I wanted to write about their work.

CG There were gallery handouts.

MD Yes, and I published almost all of them in a bookform after closing the galleries. In 1984 I published all of the essays I had written for the galleries in Bologna and Rome. In 2010 and 2012 all of the essays I had written for the galleries in Boston and New York (with Perry Rubenstein).

CG How many essays were there?

MD I didn’t count them, but between the three volumes well over 120.

CG As I recall, in the U.S. you wrote them in Italian and had someone translate them into English.

MD At least until 2001 I had the essays translated by Marguerite Shore, who is the U.S. translator for Italian reviews in Art Forum. Then I used to revise the translations because sometimes they were not close to the spirit of my original Italian text.

CG Those essays were quite challenging for me.

MD They were challenging for me too, to write.

CG You were also a concrete poet.

(Concrete poetry is an arrangement of linguistic elements in which the typographical effect is more important in conveying meaning than verbal significance. It is sometimes referred to as visual poetry, a term that has now developed a distinct meaning of its own.)

MD My poetry was not really concrete. My poetry was in the early 1960s written in a combination of languages which you could say was very close to Finnegans Wake (by James Joyce). From 1967 to 1977 it was mostly made of objects combined with words. I collected those poems in a book just last year. The minute I opened my gallery I stopped making visual poetry. I didn’t want to mix poetry with art. I knew practically all the visual artists in Italy. When I opened the gallery, some of them were expecting that I would do a show of their work. Visual poetry and art are two completely different things. To make sure that people understood this I stopped doing visual poetry and completely focused on the gallery.

CG What do you mean by visual poetry?

MD Poetry in which the visual elements are equally important and sometimes more important than the verbal element. As for me, I would find or make objects, and then with Letraset and other media I would put words or sentences on the object. Most of the time it was objects that I found or put together with elements found in different places and different times.

CG Collage.

MD Collage of objects and words.

CG Your strategy of a single work allowed you to show well known artist for which there was great interest and demand.

MD Yes, that’s probably true for my first five years in Boston, but when I was in Italy I was doing exhibitions of one single piece that nobody was asking for and I was able to sell only to Mr Maramotti. When I showed Fischl’s Birthday Boy, everyone wanted the work. But when I showed Basquiat, David Salle, Schnabel nobody wanted them.

CG How did you get those works from the galleries?

MD I never put together an exhibition working with a gallery. For every exhibition I worked with the artist, then the artist told the gallery.

CG You knew Schnabel and went to his studio?

MD Yes. In 1982 I went to the studio of Fischl, Salle, and Schnabel, told them I wanted to do an exhibition with one single work by them, and selected the work. Then they told their gallery that I would do a show in Rome with that specific work. (Diacono also showed Schnabel in Boston). When I showed Eric Fischl, he was not with Mary Boone at that time.

CG Did you give her a commission on the sale?

MD For Schnabel I gave a commission to Mary Boone. For Eric Fischl I didn’t give a commission to anybody because I worked directly with him. For Basquiat, I got the work in 1982 directly from Annina Nosei, with whom I had been friends for many years. I bought the work from her, then did the show with the painting, Il campo vicino l’altra strada.

CG Did you meet him?

MD Yes, later. In 1984, when I was in NY, I met him a a few times. The first time, I called him on the phone, I think he came with another person, we met in the street, in Houston Street, between West Broadway and Wooster. I was with Annina Nosei, and he didn’t want to talk too long with me because he didn’t want to talk to Annina Nosei. The next time I met him, it was in Mary Boone’s gallery: she showed him the collection of essays I had written for the gallery in Italy, and pointed to him the essay I had written on his work. He was very polite but we didn’t exchange many words, didn’t have much of a conversation. He was completely involved with himself, at least with regard to the three times I met him. The third time was at a dinner with Francesco Clemente.

CG Did he read your essay on him?

MD Of course not, it was in Italian. He just looked at his picture. That painting, by the way, I did not sell in Italy. I sold it to one of my two silent partners in the Rome gallery: I was closing the gallery, and was moving to New York. I sold to my partners my share of all the works we owned as a gallery.

CG What was again the name of the painting.

MD It was Il campo vicino l’altra strada, “The Field Next to the Other Road.”

(“The Field Next to the Other Road,” 1982, acrylic, enamel spray paint, oilstick, metallic paint and ink on canvas, 87 x 158 in. (220.9 x 401.3 cm.) Painted during a stay in Modena, Italy, he created a rather unusual large-scale painting. Soaked in pastel beige with the presence of his trademark red and black, it is one of his early works, a strong statement of his intentions as an artist and an overture to a type of character which marked his entire career.+

This painting sold at auction two years ago for $35 million.

CG Did you ever make any money?

MD Just enough to live and buy a one-bedroom apartment.

CG We are talking about works you showed that became valuable later, and yet at the time you just survived.

MD For example, the Eric Fischl painting I sold to Mr. Maramotti for $17,000, from which I made two or three thousand dollars. I had to pay the shipping expenses and gave around $9-10,000 to Fischl. Around 2007, Mary Boone called me and said, “Mario I have a collector in Switzerland who would like to buy the painting. I would pay $5 million for the painting, and give you $500,000 if you persuade Mr. Maramotti to sell it.” Which of course I didn’t.

CG Did you try?

MD No. I told the younger Mr. Maramotti, Luigi, that Mary Boone wanted to buy the painting for $5 million. He said no way. Already in 1986 or 1987, I had gone to see Fischl and he had asked, “Mario Mr. Saatchi would like to buy the painting, he would pay $1 million.” When I told the older Mr. Maramotti that Saatchi was ready to buy the painting for $1 million”, he said, “Oh, then I am $1 million richer.”

CG You had very good relationships with the artists.

MD Yes, and my major collector was Mr. Maramotti, and we became close friends.

CG I recall you telling me that Salle and Schnabel were cooks. Early on they earned money as chefs.

MD That was much before I showed them, in the early 1970s. David Salle was working as a chef and Schnabel as a dish washer at Max’s Kansas City. The people who were working and eating/drinking there, they were all artists. In 1969 I went a couple of times with Vito Acconci.

CG I spent a lot of time there. During happy hour I nursed a glass of wine and had dinner on the chicken wings. I knew Mickey Ruskin and he later had a home in the Berkshires. He was very good to artists and took work to cover their bar tabs. Andy and his crew came in each night and sat in the back under a Flavin.

What is your current status? Are you still active as a dealer?

MD Primarily I am active as an unofficial curator of the Maramotti Collection. They support me financially. It involved a lot of traveling until 2015, when I had a hip replacement surgery. Then in 2016 I had knee replacement, and later a surgery on my spine. After that one, I was no longer able to travel not just to Italy but also to New York. And I walk with a cane.

CG You used to spend a month each year in Italy.

MD Until 2015 I was going to Italy two or three times a year. And staying two or three weeks during each visit.

CG Why didn’t you go back to live in Italy?

MD I hate Italy.

CG I knew you would say that, but why?

MD Because of what Italy is. It’s a corrupt and backward country. Not because of the people, but because of the ruling political class. The main political parties and the government which I have despised all of my life.

CG Were you a Marxist?

MD In the year 1956, for one year, I was a member of the Communist Party. When the Russian tanks invaded Hungary I gave up my Communist Party’s membership card. From then on, I have been A Leftist Without a Party.

CG But you are living in the land of Trump.

MD When I moved to the United States first in 1967, then in 1972, and finally in 1985 I had never heard of Donald Trump. Nobody knew his name then. And it was then a different United States. I chose to go to Berkeley because of the Free Speech movement.

CG If you say that Italy is corrupt and reactionary what about the US?

MD I am a US citizen and now 90-years-old. I don’t know where else to go. All the world is the same.

CG Isn’t that the truth. How are you coping with quarantine?

MD I’m staying home, going out once or twice a week to buy food. For an hour, and that’s it.

CG How are you staying busy?

MD I spend half of the day answering e.mails. The other half answering the phone. I am working mostly along the line of the work I have done in the previous 12 years. And the work I have done between 1960 and 2000.

CG What are the plans for your archive?

MD When I am no longer here, everything I have will go to the Maramotti Collection.

CG You must have amazing documentation of the works you sold to them.

MD Documentation of the gallery is already at the Maramotti Collection. I have a collection of 20th century avant-garde books, when I’m no longer here it goes to the Maramotti Collection.

CG What about your wife and the estate?

MD I have made a trust, while we live, both me and my wife, they support us financially.

CG Do you regret the time you spent in Boston?

MD No, not at all. Between 1985 and 2015 Boston was where I spent my life with my wife, but most of the work I was doing was centered in New York. Until I had those three surgeries, I was going to New York twice a month, visiting studios and galleries. Most of all I was looking at the work of younger artists.

CG Why not just move to New York?

MD Because of my wife. Also, because, frankly, in retrospect, if I lived in New York I could not have done all the work I have done in Boston. I did not have the interest or the money to set up a gallery representing artists and taking care of their business. If I had set up a gallery in New York, I would have had to choose twelve to fifteen artists and keep showing the same artists every two years.

In Boston, the reason so many artists decided to show with me was because I told them, “I will show one or two works and write an essay”, I told them about which artists I wrote essays for in Italy. And they would all agree to do the show.

The only artists who refused to do a show were Robert Gober and Jeff Koons. For Jeff Koons I didn’t care so much, but for Robert Gober I was disappointed. I went many times to the studio to discuss with him. When we decided to do the show, he told me “Mario, I’m sorry, but Paula Cooper doesn’t want me to do the show.” Maybe the gallery didn’t want to give up a sale?

CG And Koons?

MD I didn’t actually ask to do a show with him. I asked to do a show of him with Meyer Vaisman and Heim Steinbach but he refused. Even if he had agreed to do a show all by himself I am sure Ileana Sonnabend wouldn’t let him do it.

CG What do you think of his work?

MD No comment.

CG Can you give me a few more words?

MD No.

CG I’ve enjoyed talking with you Mario. Thank you so much.

Postscript. A reply to some email questions.

MD My gallery in New York with Perry Rubenstein, on Spring Street, was in the same building where Andrea Rosen and Luhring/Augustine were. It lasted less than two years, from early 1992 to summer 1993 and closed because the art market had collapsed.

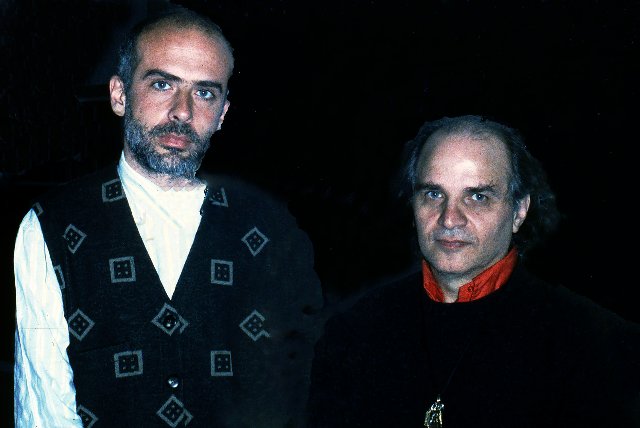

Perry and I had been friends since 1983. We loved the same artists of that time (neo-expressionists and neo-geos). We had met at the dinner after the opening of Francesco Clemente’s exhibition in London, at Anthony d’Offay, in 1983. He lent me $30,000 to help me open the gallery in Boston in 1985. A couple of months after the gallery opened with a 22-feet Alex Katz painting that I of course didn’t sell, Perry sold for me a major Kounellis work to a Japanese collector. The commission from that sale enabled me to repay in full the $30,000 he had lent me

In 2000 I closed my gallery on South Street (it was the year of my 70th birthday). I was looking to some kind of new activity in Italy, which didn’t materialize. So first I rented a studio as an office on Beacon Street near Washington Square. Then I moved into a space at 119 Braintree Street, where a good number of Boston artists had a studio.

I started to do there shows with a single work on an empty wall, calling the space and shows Wall Site. I did a few shows, and stayed there for about a year. Then Elmar Seibel offered me for free the big, slightly curved wall of Ars Libri that hides the bookstore’s shelves from the street.

From 2002 until January 2008 I did exhibitions there with a single large work that I had commissioned to the artists. All the works I exhibited at Ars Libri are now in the Maramotti Collection in Reggio Emilia, Italy, which opened to the public as a private museum in the fall of 2007, and for which I have been organizing exhibitions since 2008.

Link to Collezione Maramotti. Link to Diacono video