British Pop Artist Richard Hamilton

Co Curated by Tate Modern and London's ICA

By: Paul Black - Apr 27, 2014

Richard Hamilton’s work chronicles socio-cultural changes throughout the twentieth century, at the same time as it embraces the rise of technology. The artist translates the Duchampian language of the object with a populist bent. His was an art of disparate subject matters and methods, from ploughs and toasters to the iconography of the “Swinging Sixties” (an iconography that the artist helped to create) via Goya, Da Vinci, and James Joyce. The father of Pop Art, and the Grandfather of Brit Art; Richard Hamilton was an artist with an analytical gaze, paired with a methodical twist not echoed by his Pop Art peers.

Hamilton was one of the first artists to embrace digital technology as a medium for exploration. This was a reflection of a futurist ideology in using technology to enhance human ability, and also, one could say, to increase the ability of the artist to communicate. Hamilton was always at the forefront in appropriating contemporary methods of production, an aspect mirrored by a lifelong fascination with industrial design.

From the 1950s austerity to the introduction of American products and design into a British marketplace; the epoch of consumerist culture and capitalist growth would turn the stoic 50s of Britain into the swinging, amoral 60s.

With a Duchampian response to the consumerist objects of the time, the ready-mades and the found objects in his art always possessed a relevance to the period. One example would be the artist’s Braun toothbrush with a candy top, which served to reflect a Duchampian non-authorship in art, while at the same time highlighting the all-pervasive design influence of the day with a subversive wink to the viewer.

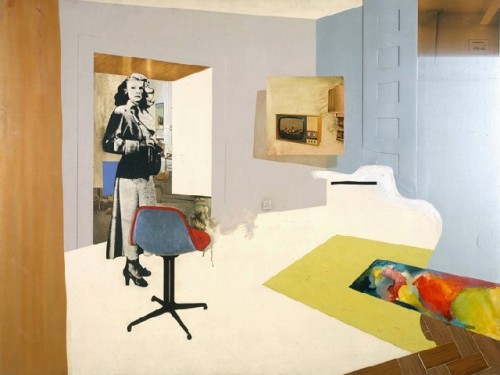

From his Reapers of 1949, to the artist’s Just what is it that make today’s new homes so different, so appealing? from 1956, Hamilton was along for the ride. He reflected on each decade, often seeming to ring in the cultural sea change before the prevailing Zeitgeist took hold.

This was a journey that saw the artist’s work as utterly varied, yet completely consistent; Hamilton’s art is at once a juxtaposition and reflection of the early post-war decades and their swift cultural and moral ascension, or decline, depending on your perspective. At times the artist’s work can now be seen as completely prescient of the socio-cultural changes to come.

This Is Tomorrow is the re-creation of the 1956 installation that was a collaboration between artists and architects, in this case with John Voelcker and John McHale, that includes the collaged images of film posters, sci-fi imagery, and advertising. This is part of a series that was to become known as the Fun-House—including sensory stimuli and optical illusions—with a jukebox churning out greatest hits. With its bright colours, sounds, and multi-media approach, the piece balked against the austerity of the decade in which it was created, and heralded the 1960s before they had even arrived.

Hamilton meticulously devoured imagery from popular culture and recycled it into collage, screen print, sculpture and painting; the latter being a method that separated the artist from Duchampian purists he was an innovative and technical painter of various styles, engaging with a multitude of subjects. Hamilton was a true “modernist” in its broadest sense.

This interest in reflecting the socio-cultural events of popular culture are evident in the works Swingeing London 67 showing the arrest of Mick Jagger handcuffed to the gallery owner Robert Fraser, titled after the judges reference to a swingeing sentence Hamilton’s paintings from the television images of the Kent State University Shootings have also been important in the works of artist Richard Prince. Both of these works are concerned with the importance and meaning of the image as a socio-cultural value.

In fact, Hamilton would do his own form of Protest Picture much like the artist Richard Prince – often an indictment of power; whether those were attacks on that of Gaitskell, or Thatcher, or Tony Blair as a gun slinger in the work Shock and Awe – Hamilton’s work was not without political statement as a chronicler of his times. The artist was “passionately responsive” to every decade through which he passed.

After the death of Marilyn Monroe, Hamilton chanced upon a contact sheet of her images from a beach shoot by photographer George Barris in which Monroe, to quote the artist, had actively caused the “violent obliteration of her own image” in scratching out the images that she did not want to be published. The images are recreated in My Marilyn with painterly gestures reflecting that of Monroe’s savage defilements. These works have a direct relationship to Warhol’s use of Marilyn Monroe as an iconic pop image of socio-cultural value; with Hamilton’s use there is also an intimacy that is evocative of an individual’s perception of their own value as an image in popular culture, and the loneliness that accompanies placing that value on one’s self.

One enduring trend throughout Hamilton’s career was the creation of Polaroid portraits of himself by fellow artists. These were published in four volumes and spanned a thirty-year period. With portraits of the artist created by the art glitterati of the day, from Lichtenstein to Lennon. Hamilton began to recognise the sensibility of each creator in the corresponding image. For example, Francis Bacon’s Polaroids of the artist were blurred and poorly lit. They were quite reminiscent of his paintings.

Fascination for this observation turned into a request by Hamilton for Bacon to paint into the images. But when Bacon declined, Hamilton attempted to teach himself Bacon’s brushstroke, and with that created Portrait Of The Artist By Francis Bacon this was simultaneously a work of photography by Bacon and a painting by Hamilton. It was a slyly inadvertent collaboration between arguably the greatest British painter of the twentieth century, and possibly the most innovative British artist of his generation, and perhaps our own.

Reposted courtesy of New York Arts Magazine.