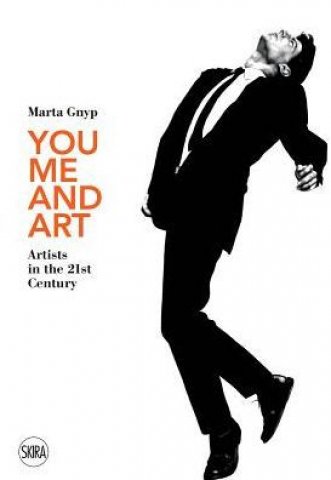

You Me and Art: Artists in the 21st Century

A Book of Interviews by Marta Gynp

By: Charles Giuliano - Apr 27, 2019

You Me and Art: Artists in the 21st Century

By Marta Gynp

296 Pages, illustrated

Skira, Milan, 2018

Interviews with: Carl Andre, Michael Borremans, Mark Bradford, Glenn Brown, Mary Corse, Anthony d’Offay, Wojciech Fangor, Adiran Ghenie, Mark Grotjahn, Damien Hirst, William Kentridge, Robert Longo, Sarah Lucas, Shirin Neshat, Demetrio Paparoni, Francois Pinault, Sean Scully, Pat Steir, Kaari Upson, Danh Vo

In 1550 Giorgio Vasari published “Le Vite de' più eccellenti pittori, scultori, e architettori” (“The Lives of the Most Excellent Painters, Sculptors, and Architects”).

The task at hand considers the 2018 Skira publication “You Me and Art: Artists in the 21st Century” by the Dutch art historian, Marta Gynp.

To compare and contrast critical writing over a span of centuries is arguably a stretch.

Vasari was a polymath: Artist, architect, writer, and founder of modern art history. It was that diversity that he brought to researching prior artists and interacting with his peers.

While Gynp focuses on living artists she brings experience and insights to an eclectic range of interviews with global artists. Where artists are born no longer defines where they live and work. Some of these interviews were conducted in Berlin where she is based.

The primary commonality in the Vasari tradition is approaching the artist as the primary source for understanding the work.

In a skilled interviewer that entails a chameleon-like ability to adapt to the palette evoked by the individual being questioned. Like a good lawyer, it is best to ask questions when knowing or anticipating the answers.

It’s tricky to ask a question, listen and interact, while thinking ahead to direct the dialogue. A well crafted interview, of which there are an impressive number in Gynp’s engaging book, is like a chess game. One must always be planning the next few moves.

A limitation of interviews is that they are only as sharp and insightful as the subject. Many artists are not that interesting to talk with. This is why they are artists and not writers. Some, however, talk a better game than the work itself. Many critics and curators, concerned with developing their own ideas, prefer little or no contact other than social, with the artist. There is the theory that, once it leaves the studio, the work no longer belongs to the artist. It must exist on its own terms.

The face-to-face practice of Gynp, while not unique and perhaps even ancient, is refreshing. In her book of encounters the artist is the primary, but not exclusive, resource for engaging the work.

Art is a voyage and the critic/ journalist may be a fellow traveler. Often it seems that more is learned in the studio than libraries.

The exchange with Sarah Lucas, for example, is stunning and engaging. Her seemingly simplistic, Duchampian visual puns had struck me as slight, smarmy and vulgar. Reading her comments confirmed those instincts but perversely switched from negative to positive. Through their dialogue I came to understand concerns that inform the work and make it interesting. It has a rough, punkish, edgy quality.

For a critic the challenge is to separate authentic puck created from the ergot of poverty from the repulsion of upscale, tattered, designer jeans. Sitting there in a photo wearing a T-shirt with ersarz fried eggs over the breasts is either outré or hilariously brilliant. Critical response can swing both ways. Particularly when grunge art goes for six figures and is seen in museums.

Through Lucas we learned a lot about the London scene, its attractions, as well as the need for distance as a matter of survival. It explains how so many artists and rockers evolve from slums and squats to estates and villas. Think Adele.

That’s a thread for understanding Damien Hirst, now 53, one of the mega-rich, global artists of his generation. When the work began to sell the largest portion of profit went back into hiring assistants to make more work.

The discussion of ethics and aesthetics of having other people produce the work is familiar and overblown. Why do we insist on uniqueness and originality in the fine arts but not in film, theatre or architecture? It can take ten minutes to roll the credits for a major film.

Consider the studio traditions of Raphael and Rubens. What’s the difference between that and the studios of Warhol, Koons and Hirst? The concept and design are as important as the individual that makes the work.

The interviews of Gynp often evoke the humanity of her subjects. There is enough easy familiarity to get behind the defensive barriers of superstars like Hirst. Yes, he was a bad boy, and enjoys what he left behind. He brags about never getting hangovers until he quit drinking. There is an amusing anecdote about refusing to share a cigarette with a gallerist. It’s weird when hard rockers start drinking coke rather than snorting it.

We see Hirst as a father and seemingly good dad. He treats his workers well and they even told him to stay away. Before becoming sober he would show up and get them to party. So the work wasn’t getting done. We learn that he made prototypes for the endless "Spin" and "Spot" paintings. Hirst instructs assistants how to create to his specs.

There is a tradition of contemporary artists who apprenticed as assistants. For a Russian project Hirst brought his studio. A young curator organized a show for them.

Although Hirst collects cars, Gnyp reports some 15, he never learned to drive. His friends drive him and he uses the time to think. As Groucho would say “Call me a cab.”

The interview with Carl Andre explores formal aspects of minimalism. There is the oft told tale of interactions with fellow Andover Academy alumnus, Frank Stella. Andre grew up in working class Quincy, while Stella, the son of a doctor, was raised in upscale Melrose. Andre has always projected a socialist worker ethic.

Significantly, Stella advised that the uncarved side of timber was just as interesting and sculptural. That was a way around Andre’s admitted lack of skills. It also meant, early on, not needing a studio or just a corner of Stella’s. It involved material, easily stacked and stored, arranged in varying configurations. He allows freedom for curators when installing it. Checker grids of different hued, metal plates are placed on the floor of a gallery or museum. One always feels apprehension about walking on the work. That’s a part of its charm. To do so is an act of hipster hubris.

We anticipated the moment when discussion would turn to the death of his wife Ana Mendieta. With Andre’s fourth and current wife, Melissa Kretschmer, present during the interview he related events of that tragic evening. It feels creepy when he talks of her as a wonderful artist and time they spent together with her family in Cuba. The art world has remained divided but a jury found him not guilty of murder. Gynp allowed him to make a benign statement without rebuttal.

A particularly insightful interview is with gallerist Anthony d’Offay. We learn that he was dealing as a teenager and in his 20’s opened a gallery on sufficient scale to represent major global artists. Space was as huge factor in this success story. Hirst talked about how the vast Charles Saatchi gallery/ museum in suburban London opened up possibilities. When I visisted many years ago it was almost impossible to find down a side street. That was before GPS. Entering the vast space, as Hirst stated, was indeed a shock and surprise.

At the time there were a handful of small galleries showing contemporary art in London. Hirst was thinking along the lines of making small collages in the manner of Kurt Schwitters. His dream came true when Saatchi showed and acquired large early pieces. From there it was no going back. Hirst and other young artists focused on scale appropriate to museums and biennials.

The interview with Anthony d’Offay is seminal. It reveals the degree of interconnection of the emerging London scene. The young Hirst, then an art student and entrepreneur, worked as an installer for the gallery. Young artists were exposed to the array of modern masters: Kiefer and Beuys, Warhol. The dialogue with the renowned gallerist is accessible, charming, and insightful.

It was the end of a gallery day in Soho in 1995. That meant climbing stairs to the Annina Nosei gallery. Photographs of veiled women covered with henna texts in farsi intrigued me. I was taking slides for my avant-garde seminar at Boston University. Shirin Neshat was born in Iran in 1957. She left Iran in 1975 and earned a BA, MA and MFA at University of California, Berkley. She was a late bloomer and had her first solo show at the non profit Franklin Furnace in 1993. For the show I documented she was working with still images. Her career exploded when she later worked with film and video.

As Gynp learned the artist had mixed feelings about showing film in galleries. That soon changed. By 1999, she won the International Award of the XLVIII Venice Biennale. A decade later she won a Silver Lion for best director at the 66th Venice Film Festival.

Gynp discusses issues of heritage, identity and gender. That entails women in cultures that Americans view as repressive and medieval. We are surprised by her neutrality. Neshat respects Iranian traditions while embracing Western independence. She states that “I’ve had a long obsession with strong middle eastern artists.” With “Looking for Oum Kulthum” she expresses concerns as an Iranian woman, whose language is farsi, creating a film about a legendary Egyptian singer. While sharing religion there are enormous social and political differences between Iranians and Arabs.

Crossing so many lines makes the work of Neshat particularly intriguing. These conflicts evoked one of the most poignant, poetic, and resonant chapters of the book.

The interviews that worked best for me entailed familiar artists and work. I recalled an installation at Metro Pictures of 300 plus small drawings by Robert Longo. It was the culmination of a year long project of daily drawings. They were inspired by photo journalism and stock photos. One was a rendering of a classic image by Cindy Sherman. They lived together when she made the self portraits that launched her career.

Initially, only a few of the works from the show sold. Collectors didn’t know what to make of the project. The images were confoundingly generic. Over time a few more sold. Then a collector bought a hundred. That turned the tide and now all of the show has been sold.

That narrative underscores the element of risk taking. Most artists state that their primary focus is making the work. When and if fame and fortune occur it gets complicated. As Lucas commented that meant getting a better flat or a big TV.

For a handful of artists the fame game is part of the work. Examples are Warhol and Koons, and in a more funky way, Hirst. Celebrity artists always get ink but what about those who barely manage their fifteen minutes?

Today’s New York Times tells of the “comeback” of 69-year-old Ross Bleckner. He hasn’t shown in five years and his former dealer, Mary Boone, is serving time for tax evasion. Her gallery is closing in May. When she gets out of the slammer the media will be all over her comeback. How many mid career artists are out there surfing and trying to catch another wave? A careful reading of Gynp underscore that balancing act.

She conversed with Danh Vo a Vietnamese artist whose work was unfamiliar to me. The practice in part entails collaborations with his father. It seems he had a store and cheated on taxes. Beyond keeping double books, with exquisite calligraphy, he falsified daily receipts. Later the artist’s sister had a store that took in twenty times his daily revenue. There was no need to evade taxes but the senior Vo wanted to ‘assist’ her. The artist discusses mixed feeling about that. His work entails forged documents created by his father. This complex conceptual aspect of the work will end with the passing of his father. Similarly, Warhol used the remarkable script of his mother Julia in his early work.

Gynp asked Vo interesting questions.

MG: I was under the impression that you had a very clear vision of what you wanted from your art, from the very beginning.

DV: That isn’t true. I have no clear idea of where to go. But that’s the beauty of it. I think that must be the most boring thing: to know where you are heading.

As Gauguin put it “D'où Venons Nous / Que Sommes Nous / Où Allons Nous.”