The Steins Collect: Matisse, Picasso, and the Parisian Avant-Garde

Americans in Paris Celebrated at the Metropolitan Museum of Art

By: Charles Giuliano - Apr 28, 2012

The Steins Collect: Matisse, Picasso, and the Parisian Avant-Garde

February 28 – June 3, 2012

The Metropolitan Museum of Art

The Tisch Galleries

From 1903 through 1914 Leo (1872-1947) and Gertrude Stein (1874-1946) shared his studio at 27, rue de Fleurus in Paris. They had both studied at Harvard (she at what later became known as Radcliffe College) after which she declined to complete a degree in medicine at Johns Hopkins in Baltimore. Leo left Harvard after two years to travel. He completed his degree at Johns Hopkins in 1898.

There she met Claribel Cone who earned a degree in medicine. Gertrude acquired from Claribel and her sister Etta an interest in art and the practice of Saturday night salons. The Cones later moved to Paris where, through Gertrude and Leo, they were introduced to Matisse whom they collected in depth. Gertrude also sold them works when she needed money.

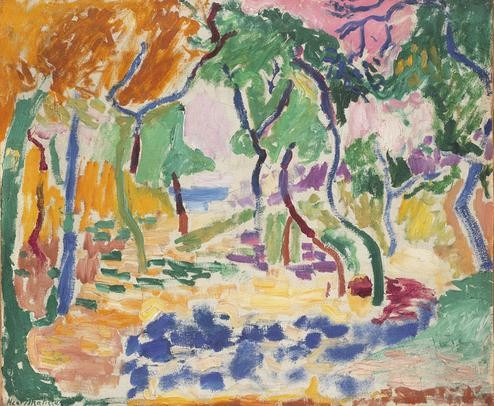

Leo studied the fine arts at Harvard. He was interested in but could not afford the Impressionists. Other than one small work by Manet he was able to acquire less expensive works by Renoir and the post impressionists Paul Cezanne and Paul Gauguin. The siblings acquired Matisse but argued over Picasso. These young School of Paris artists, whom they are credited with discovering, fit their modest budget at least initially.

By 1914 they separated and split the collection. Leo, who proved to be more conservative, kept the Renoirs while Gertrude made a clean sweep of the Picassos. Leo was becoming progressively more hard of hearing while Alice B. Toklas (1877-1967) had moved in with them unhinging the social symmetry.

As the salons became populous Leo required more privacy. He returned to America to work as a journalist but eventually settled near Florence with Nina Auzias. They married in 1921. Two years after the death of Leo she took her life.

The invitation only salons proved to be a matrix of the avant-garde and Americans in Paris. What Gertrude later dubbed The Lost Generation. Because no French museum championed the work the salons were of enormous significance. Not only might one view the most advanced works of art but, as Hemingway chronicled in A Movable Feast, it is where artists and writers gathered to discuss and debate. Famously, it is how Picasso and Matisse met forming a lifelong relationship as friends, colleagues and rivals.

There were many reasons why the Lost Generation gathered in Paris. For those living on trust funds, Leo and Gertrude or Gerald and Sarah Murphy and his Yale friend, Cole Porter, or Harry Crosby (Black Sun Press) the franc was worth more than the dollar. As F. Scott Fitzgerald noted (he and Zelda were regulars at the Stein salons) “Living well is the best revenge.” This was more plausible in France.

Paris was home to legendary African Americans like the music hall entertainer Josephine Baker (later a member of the Resistance) and New Orleans soprano sax player Sidney Bechet. Tenor sax player, Coleman Hawkins, passed through Paris and resided in Belgium. Later, in the 1960s, the tenor sax players Ben Webster and Dexter Gordon resided in Copenhagen.

The City of Lights was refuge to homosexuals, writers and artists (Max Weber, Stuart Davis, Stanton Macdonald Wright, Patrick Henry Bruce). Empty churches and ramshackle dwellings like the notorious Le Bateau Lavoir provided cheap studios and compelling camaraderie. Artists and bohemians gathered at Les Deux Magots in the Saint-Germain area of Paris.

While Gertrude and Leo were in the thick of it this was mostly through the generosity and business acumen of their older brother Michael. They and a brother Simon and sister, Bertha, were the children of Daniel and Amelia Stein of Allegheny, Pennsylvanian near Pittsburgh. The family fortune was based on railroads and real estate.

When the children were quite young the family lived abroad eventually settling near Oakland. The father, described as a tyrant, died shy of sixty leaving a tangle of debts. Their mother also died young of stomach cancer.

Michael, the eldest, became manager of San Francisco's street cars. He sold this business to Colis P. Huntington. Michael also speculated on building row housing. As head of the family Michael sent Gertrude to Baltimore and her aunts. Having consolidated the family business interests, in 1904, Michael moved to Paris with his wife Sarah (1870-1953).

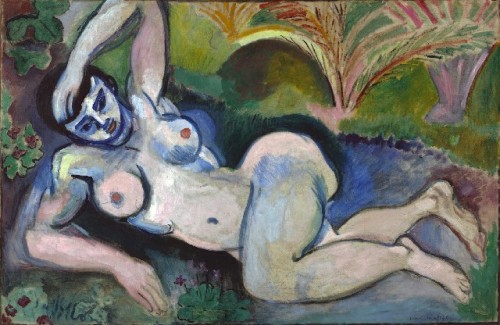

Through Leo and Gertrude their brother and sister in law were introduced to Matisse and became his most important early collectors. For the seminal 1913 Armory Show Leo loaned his Matisse masterpiece the 1907 "Blue Nude." It was later sold to the Cone Sisters and was part of their seminal collection bequeathed to the Baltimore Museum of Art.

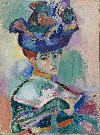

Gertude and Leo borrowed money from Michael to buy their first Matisse "Woman with a Hat" which caused a scandal in the 1905 Salon d’Automne. They later sold it to Michael who in turn sold it to a San Francisco collector who donated it to the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art.

In addition to buying his work Sarah helped Matisse to teach carefully selected students in addition to herself. He converted his studio at an old convent building on the rue de Sèvres into a school. Among the 200 works on view in the Met exhibition (which traveled to New York from San Francisco and Paris) one gallery of interesting but minor artists, (including Sarah), is dedicated to this brief activity of Matisse. He tried to encourage students to find their own style rather than copy him.

Compared to the prodigy Picasso the work of Matisse evolved slowly. He came to art fairly late after abandoning the family mandate that he pursue the law.

In 1914 Michael and Sarah loaned 19 of their best works by Matisse to Fritz Gurlitt Gallery in Berlin. With the outbreak of war the paintings were confiscated. After a drawn out lawsuit they were sold.

With a unique gesture of concern for their loss Matisse created a pair of portraits of Michael and Sarah. They are now owned by the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art.

In the San Francisco Chronicle the critic Kenneth Baker wrote “The Matisse portraits of Michael and Sarah serve as emblems of ‘The Steins Collect’ in the San Francisco launch of its international tour. The Metropolitan Museum of Art's 1906 Picasso portrait of Gertrude - her only gift to a museum - will probably serve that purpose when the show travels to New York.”

When Michael and Sarah settled in Palo Alto, California, in 1935, they brought with them the first significant group of works by Matisse to be seen in America since the Armory Show of 1913.

It is reported that Gertrude was miffed that Matisse never asked her to pose for him. But there were some 80 sessions with Picasso. Finally in frustration he wiped out the face. While in the midst of the transition to analytical cubism, under the influence of “primitive” art, he completed the image rendering her as a rigid mask. She did not pose for the finished version.

When shown the portrait it is said that she liked the painting but that it didn’t resemble her. According to legend he responded “You will grow to resemble it.”

We have her later published remarks. "I was and I still am satisfied with my portrait," Gertrude wrote in "Picasso," published shortly before World War II. "For me, it is I, and it is the only reproduction of me which is always I, for me."

Of the four collecting Steins (including Sarah) Gertrude is best known by the general public. It is usual to comment that she is among the most famous unread authors. She claimed to be equal if not superior to Hemingway. In her view he stole her seminal technique of simple declarative sentences. He savaged her in " A Movable Feast” perhaps underscoring some of the truth of their intense discussions of literature.

During my lifetime attempts to read her have waxed and waned. During summer school at Harvard I played hooky from chemistry to listen to recordings of poets reciting their work in the library. Her deadpan cadence was infectious but less so than the melodious Welsh poet Dylan Thomas.

In 1933 she had a best seller in “Autobiogaphy of Alice B. Tolkas” which launched an American lecture tour. In the late 1960s my girlfriend Arden Harrison enjoyed it as well as Stein's first book "Three Lives." Keeping pace with the dialogue I slogged through several of her books.

Let the following passage give a sense of what that is like. In "Everybody's Autobiography" she wrote "You see I said continuing to Pablo you can't stand looking at Jean Cocteau's drawings, it does something to you, they are more offensive than drawings that are just bad drawings now that's the way it is with your poetry it is more offensive than just bad poetry I do not know why but it just is, somebody who can really do something very well when he does something else which he cannot do and in which he cannot live it is particularly repellent, now you I said to him, you never read a book in your life that was not written by a friend and then not then and you never had any feelings about any words, words annoy you more than they do anything else so how can you write you know better you yourself know better, well he said getting truculent, you yourself always said I was an extraordinary person well then an extraordinary person can do anything, ah I said catching him by the lapels of his coat and shaking him, you are extraordinary within your limits but your limits are extraordinarily there and I said shaking him hard, you know it, you know it as well as I know it, it is all right you are doing this to get rid of everything that has been too much for you all right all right go on doing it but don't go on trying to make me tell you it is poetry and I shook him again, well he said supposing I do know it, what will I do, what will you do said I and I kissed him, you will go on until your are more cheerful or less dismal and then you will, yes he said, and then you will paint a very beautiful picture and then more of them, and I kissed him again, yes said he."

Between now and June 3 make every effort to visit the Met. The Steins Collect: Matisse, Picasso, and the Parisian Avant-Garde is, unquestionably, among the most remarkable and insightful exhibitions of early French modernism ever assembled.

There was an earlier, smaller version Four Americans in Paris: The Collections of Gertrude Stein and Her Family at the Museum of Modern Art, December 19, 1970 to March 1, 1971.

That earlier project was stimulated by the sale of 38 paintings, drawings and collages by Picasso and nine works by his colleague, the Cubist painter Juan Gris. When Toklas died in 1967 they became the property of a diverse group of Stein heirs with a value reported as some $6.5 million. These works and others comprised the MoMA exhibition.

Alice outlived her partner by some 21 years. She earned royalties from her cook books and Gertrude's writings but lived modestly. Her priceless collection was uninsured as it had been during Gertrude’s lifetime. During vacations and time away from home the work was unprotected and there were some thefts. This occured when she escaped the harsh Paris winter living in a pensione in Rome. The Stein heirs managed to strip the walls and deposit the works in bank vaults. To prepare them for eventual sale they had to be secretly moved from France where they might be confiscated by the French government as national treasures.

There was great complexity, for example, in settling Picasso’s estate. What the government took in lieu of estate taxes forms the nucleus of the Picasso Museum in Paris.

What the Met exhibition demonstrates is how many great works passed through the collections of the Steins. In later years works they acquired for a pittance became a resource to support their lifestyle. It was an investment from which they withdrew dividends. It is an approach that blurs the boundaries between collectors who also function as private dealers.

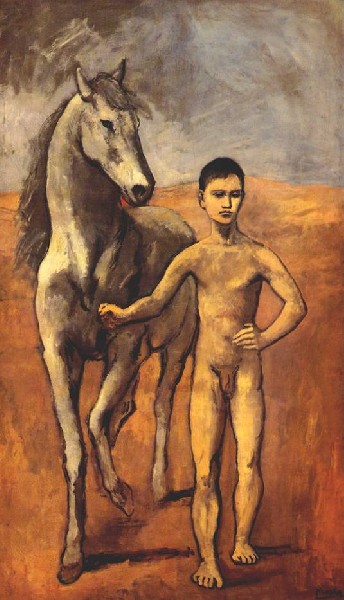

Dr. Albert C. Barnes, the eccentric American collector bought his greatest Matisse “La Joie de vivre” while visiting with Gertrude and Alice. To promote her literary efforts Gertrude sold works. She also traded. In 1913, for example, she swapped three large early Picassos to the dealer Kahnweiler in exchange for $400 plus a new Picasso picture, "The Man in Black" from his Circus Period. It was resold the same year to the Russian collector Ivan Morosov for $320. It is now in the Pushkin Museum, Moscow.

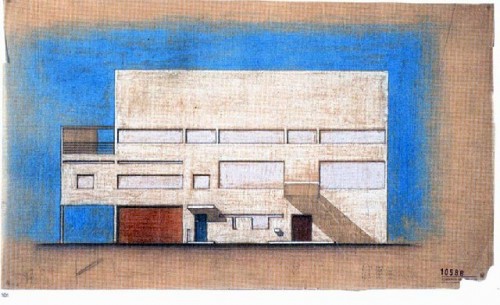

Michael and Sarah sold art when, with Gabrielle Colaco Osorio de Monzie (1882-1961) they commissioned Le Corbusier and Pierre Jeanneret to design a great modernist home in 1926-28. It is regarded as one of the masterpieces of domestic architecture in France. The following year Le Corbusier designed another masterpiece near Paris, Villa Savoie.

The leitmotif of this remarkable exhibition is what it reveals about great collections. It is insightful to learn that the Steins were well off but not truly wealthy. That meant the risk taking of investing in the affordable works of their contemporaries. With keen eyes and excellent taste they chose well.

When in a relatively short time they could no longer afford Picasso and Matisse they would later trade up. Their collections became flexible resources. Tracking the provenance today would be a daunting task for a team of art historians.

During the war Gertrude and Alice remained in France. Through alleged connections with the Vichy Government they escaped the grasp of the Nazis. In "A Moveable Feast" Hemingway described sitting up at night with Stein drinking cognac while the sound of borbardments crept ever closer to Paris.

"In a few yellowing notebooks tucked away in the Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library at Yale University," according to Dartmouth Professor Barbara Will in "Unlikely Collaboration: Gertrude Stein, Bernard Faÿ and the Vichy Dilemma," she discussed Stein's translation of 32 speeches by Marshal Philippe Pétain. The hero of WWI was the head of the Vichy Government. Hmm.

By comparison, that other renowned American in Paris, Peggy Guggenheim, fled to New York. When the Germans were getting ever closer to Paris she was running around the city loading cabs with works she bought for bargain prices from panicked artists.

During their lives and through the estates of the four Steins the stunning works displayed in this exhibition were scattered. It makes one pause and ask what if? The Cone sisters returned to America and eventually left their collection to the Baltimore Museum of Art. Peggy Guggenheim’s collection is on view in her palazzo in Venice.

Alfred H. Barr Jr. tried to persuade Gertrude to leave her collection to MoMA. "You can be a museum," she told him, "or you can be modern, but you can't be both."