Afro-Cuban Music and Dance Rumbles Mass MoCA

Los Muñequitos de Matanzas

By: Charles Giuliano - May 01, 2011

The Hunter Center at Mass MoCA was packed last night for another of the ongoing collaborations with Jacob’s Pillow featuring the Cuban folkloric music and dance group Los Muñequitos de Matanzas.

If it takes a village a Northern Berkshires audience bonded with the traditions of rural Cuba that span centuries reaching back beyond slavery to origins in Africa. The troupe of young singers and dancers are committed to sustaining authentic interpretations that have been passed along for generations.

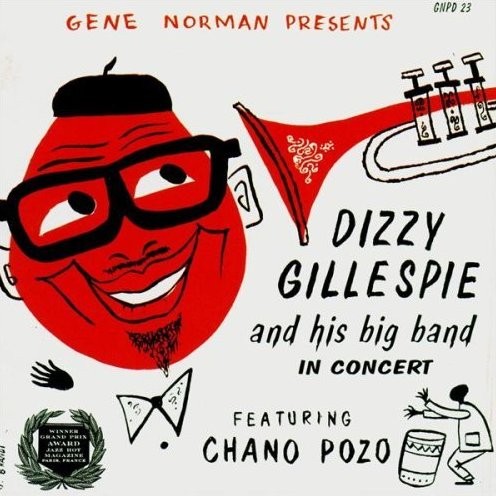

It is the echo of African drumming and chanting that inspired George Russell, in 1947, to compose the seminal “Cubano Be and Cubano Bop” for the Dizzy Gillespie Big Band. The recordings, among the most influential in the history of jazz, featured the sensational Cuban percussionist and singer Chano Pozo (January 7, 1915 – December 2, 1948).

The Russell/ Gillespie collaboration launched the genre of Latin Jazz through a confluence of Afro-Cuban percussion and chanting with the instruments of a jazz orchestra. Since then there have been many incarnations and manifestations from Tito Puente, Willie Bobo, and Mongo Santamaria, to the avant-garde approach of Paquito D’Rivera.

The purest and most soul wrenching form of Afro-Cuban jazz remains rooted in Havana. American audiences were thrilled by the film and tour of the then elderly Buena Vista Social Club.

But there was none of that last night at Mass MoCA. It was an evening of roots and origins. For purists it was the real thing. As genuine as a rum soaked, steamy night in the out back partying and dancing the slow, sensual rumba to the wee hours of dawn.

The best sense of that occurred at the end of the performance when members of the audience were invited on stage to join in the dancing. There was an older gentleman with a straw hat who had all the right moves. Perhaps it brought him back, oh too briefly, to his youth. Not to be outdone, Evelyn, an elderly Mass MoCA volunteer, got a rousing hand from the audience as she shook her bootie while twirling a colorful scarf.

In an introduction that lasted for a full half hour Joe Thompson, director of Mass MoCA, presented a representative of the family of Irene Hunter, to whose memory the evening was dedicated, who introduced, Ella Baff, artistic director of Jacob’s Pillow, who introduced a scholar from Berklee College of Music.

Basta. On with the show.

As Ella likes to say “Let’s dance.”

Not to be disrespectful. Of course we greatly appreciate the generosity of the Hunter Family that had endowed the collaborations between Pillow and MoCA. It is such a thrill to have world class dance so readily accessible. Significantly, the space at Mass MoCA is considerably larger than the capacity in Becket. Over the past dozen years that has equated to presenting companies with the broadest audience appeal.

The capacity turnout was evidence of the effectiveness of that strategy. It is also likely that it is only through support from the Hunter fund that it is possible to present such a large and expensive traveling company. At any given moment in the two part program we counted as many as 15 singers and dancers on stage. Other than costumes and props, however, there were no sets which reduce costs.

Founded in 1952, Los Muñequitos de Matanzas was first composed of musicians and percussionists who gathered casually in Matanzas, Cuba. The original members were port workers, plumbers, and masons; workers who would create music from spoons, bottles, and tables nearby as a way to unwind. The name “Los Muñequitos de Matanzas” means “Sunday cartoons from Matanzas,” and came from the title of a song on the first record they released in 1956.

In 1989 Los Muñequitos de Matanzas began to tour internationally; visiting England, Canada, Central America, South America, and Europe, and making their U.S. debut in 1992. The company first performed at Jacob’s Pillow Dance Festival in 1994 and returned in 1999.

The first half of the performance merges rhythms, songs, and dances from Afro-Cuban folkloric heritage, including Yoruba, Brikamo, Kongo, Arará, and Iyesá, while the second half contains several subgenres of Cuban Rumba such as Yambú, Guaguancó, and Columbia.

When Africans were captured and transported through the Middle Passage to be sold into slavery the few remnants of their culture that came with them were traditions of spirituality expressed through ritual, song, percussion, oral traditions and crafts.

These cultural resources were repressed but survived here and there in the Sea Islands of Georgia and the Carolinas and the unique Congo Square in New Orleans the birthplace of jazz. The purist forms of African music and dance flourished in Cuba, Haiti, and Brazil. Today, these continue as the richest and most diverse resources.

In the folk oriented first half of the program the range of African influences were most evident. While one conga player laid down the beat the three and four other percussionists overlaid polyrhythmic variations. There was a similar approach with a lead singer and three accompanists. Together the ensemble demonstrated the full range of this most simple indigenous approach.

While the percussionists and singers displayed virtuoso skills the narrative dance forms were simple and explicit to the point of simplistic and pantomimed. Even given the limitations of language barriers, to those not fluent in Spanish and the Cuban patois, the dances were so broadly illustrative than one could follow the basic plot lines.

The degree of difficulty of the dance proved to be relatively unchallenging. There were few if any wow and aha moments. Particularly when compared to other Hispanic companies presented at Mass MoCA such as Ballet Hispanico, a contemporary Latin dance company, or the amazingly athletic, jaw dropping Dance Brazil several years ago.

Overall Los Muñequitos de Matanzas provided an educational experience more than an evening of sensational entertainment.

The second part of the program with its emphasis on authentic rural rumba was more engaging. It was interesting to see the men in outlandish, gawdy gear, cutting each other in a variant of what we know today as hand jive and break dancing. It is the kind of flash dancing and foot work that evoked Sammy Davis, Jr. with his father and uncle, or the groups that perform for tips in the New York subways or in front of the steps of the Metropolitan Museum of Art.

In that sense the appearance by Los Muñequitos de Matanzas provides a base line and bench mark for African traditions in Western music and dance from Congo Square to Michael Jackson.

It was all there, roots, if you watched and listened attentively.

Or for my Haitian friend, Robert, as the four of us discussed the event over beers at the Mohawk, “Sublime. The real thing baby.”