Flemish Masters at Peabody Essex Museum

Saints, Sinners, Lovers and Fools: Three Hundred Years of Flemish Masterworks

By: Charles Giuliano - May 01, 2025

Flemish Masters in Eclectic Exhibition at Peabody Essex Museum

“Saints, Sinners, Lovers and Fools: Three Hundred Years of Flemish Masterworks" is an overview of art from 1400 to 1700. At the Peabody Essex Museum in Salem, Mass., through May 4, it includes some 150 paintings, drawings, sculptures, prints, and objects. It was co organized by the Denver Museum and Phoebus Foundation.

The Phoebus Foundation is an art foundation with philanthropic objectives. The foundation acquires works of art, and guarantees a professional framework of conservation and management. It focuses on scientific research and shares this through exhibitions, cultural expeditions, symposiums and publications.

The Phoebus Foundation was founded in 2011 to ensure the future of what started as the private collection of Fernand and Karine Huts and of the family enterprise Katoen Natie. To extract the collection from the industrial and financial risks of the Katoen Natie group of companies, it was placed in an independent legal structure, aimed at the management of its property rights. The Katoen Natie and the Huts family are not beneficiaries of the foundation. Objects from the foundation can never be sold for the benefit of the company and/or the family. The Phoebus Foundation strives to return high quality pieces to Flanders and keep them there.

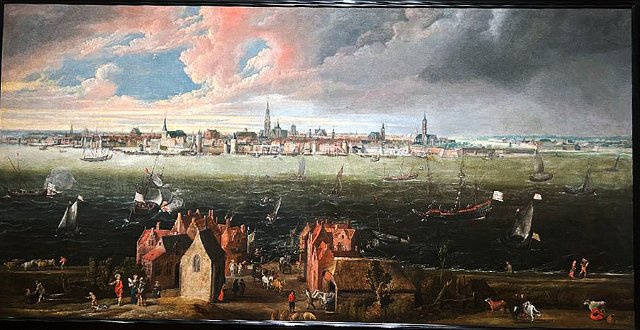

“This period is important because it had such an outsized impact on the history of art,” said Chloé M. Pelletier, the curator of the Montreal installation of the show. “Here we see the invention of oil painting and the flourishing of the publication industry. The print trade is largely based in Antwerp. In the late 16th century, Antwerp is also at the center of trade for vast global empires.

“Artists in this era had more possibilities of what they could create. It wasn’t just the Church commissioning an altarpiece,” said Pelletier, “There’s a merchant who wanted a portrait or a devotional work for their own home. The market becomes richer and richer and new genres arise to meet that market. Landscape painting emerges for the first time as an independent genre. We see genre scenes or scenes of daily life as well as those of raucous behavior.”

Flanders, now Belgium, is a relatively small region in the Low Lands below what is now the Netherlands or Holland. During the period in question it endured religious conflicts, wars, and occupation by the Austrian Hapsburg and Spanish rulers. Antwerp was one of the most active ports in Europe and more dominant than Amsterdam. Its other major cities were Ghent, Bruges and Brussels.

There was wealth and disposable income for an emerging middle class of merchants. An art market emerged to suit this bourgeois trend for ostentation and the status of acquiring the fine arts. This was a different form or patronage from the traditional sources of church and nobility. Wealthy individuals were able to commission altar pieces for home worship. We see a number of examples of this in the exhibition. There was a taste for everyday life in the flourishing of genre paintings which could be raucous and vulgar. It required no special taste or education to appreciate some of the outré and hilarious works in the exhibition especially its depictions of fools and foolish behavior.

Often self taught, artists proliferated and set up shops. They were as common as bakers and other tradesmen. Many women worked as artists with a focus on still life and portraits. Their ubiquity and contributions have been recognized by recent generations of art historians. There are representative examples of their work in the exhibition. For common folk, peasants and housewives making work for speculative sale flourished. This was the emergence of what we know as the art market. The work was shown in shops and from the homes and studios of artists.

During the late International Gothic period the Flemish Masters, including Hugo (1385/90-1426) and Jan (1390-1441) van Eyck, developed the meticulous rendering of oil paint often layered and glazed over an egg tempera underpainting. Other early masters included Rogier van der Weyden (1399/40-1464), Hans Memling (1430- 1494), Hieronymus Bosch (1450s-1516) and Pieter Bruegel (1525/30-1569). Other masters include Peter Paul Rubens (1577-1640), Jacob Jordaens (1593-1678), Anthony van Dyck (1599-1641) and Adriaen Brouwer (1605-1638).

Accompanying the exhibition is a sprawling, 432-page richly illustrated catalogue by Katharina Van Cauteren, the chief of staff of the Phoebus Foundation, who spearheaded the project.

The eclectic exhibition is organized thematically rather than chronologically. As such it is more art appreciation intended for the general audience than scholarly art history. The selection focuses on works acquired by Phoebus Foundation which was founded fairly recently. It is limited to what was available on the art market long after the masterpieces were acquired by world class museums. The leading artists are either not included in this survey or represented by minor works. What is presented is a pastiche evoking the flavor of Flemish art. This selection highlights the mandate of the foundation to collect, conserve, and promote in surveys such as what we saw in Salem.

While rich, eccentric, and flavorful I came away with a sense of several categories rather than a rich lesson on the unique and complex legacy of Flemish art. How did it differ from European art of that period? In what manner is it distinguishable from the practice of similar themes in neighboring Dutch art? The exhibition included a number of interesting and amusing examples but left too many important themes and questions unanswered. There were maps to locate Flanders but little concrete information to delineate the differences from Holland which it borders. It’s more like a visit to the zoo than a safari to appreciate wild life in its natural habitat.

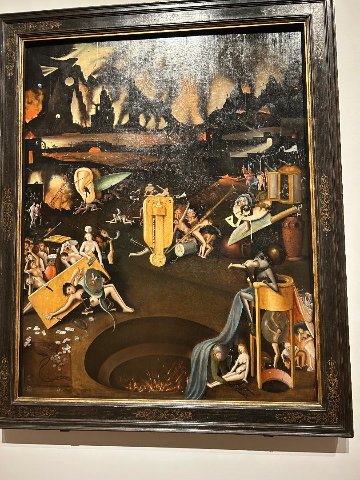

The show, however, is clever, accessible, nicely installed and entices the visitor from one gallery and category of art to another. For Salem and its audience the museum has opened the door for a rare and quite entertaining view of the School of Flemish art rather than a selection of its masterpieces. It is left to the visitor to separate the wheat from the chaff. We view, for example, a copy, in fact a detail of “Garden of Earthly Delights” by Bosch. At best it reminded me of looking long and hard at the eccentric and harrowing original in the Prado. It recalled an era when museums displayed plaster casts of classical sculptures when few people had means and access for global travel.

To be sure this exhibition has wonderful works if you have the wit and will to find them.

There is a full length van Dyck portrait of Archduchess Isabella Clara Eugenia (1625). Initially, I wondered why I should be interested in a nun however vividly she is depicted? Digging deeper my initial reaction proved to be wrong. After the death of her Austrian husband she took vows but basically governed Flanders on behalf of Spain. Research revealed that she was one of the most powerful women in Europe. There is another compelling van Dyck portrait of the young William II of Orange.

Another view of the politics she presided over is represented by a small, lively genre painting of peasants expelling Spanish troops from occupying their homes.

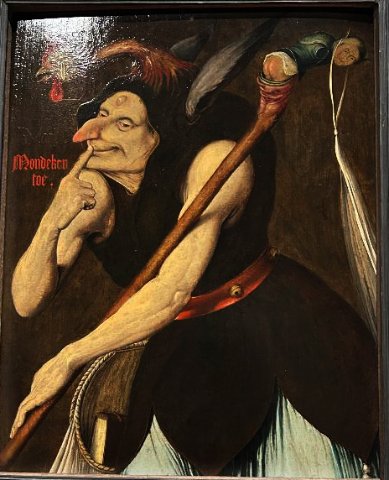

The theme of fools was witty and well explored. There is a poignant portrait of Elisabet, Court Jester of Anne of Hungary, 1525. The face of this simpleton is sad and evokes melancholy. The “fool’s” misery is exploited for the entertainment of nobility. Quinten Metsijs depicts another odd fellow “Keep Your Mouth Shut” (1528). His distorted features evoke a character from Bosch. A finger points to pursed lips below a prominent hooked nose. He wields a staff the top of which featured a tiny figure with bared buttocks. There are a lot of butt japes in Bosch.

There is all manner of tom foolery in “The Mocking of Human Follies” (circa 1550) by Frans Verbeeck. The cluttered work has many vignettes in the manner of Bruegel and Bosch. While the fools cavort a house in the distance burns down.

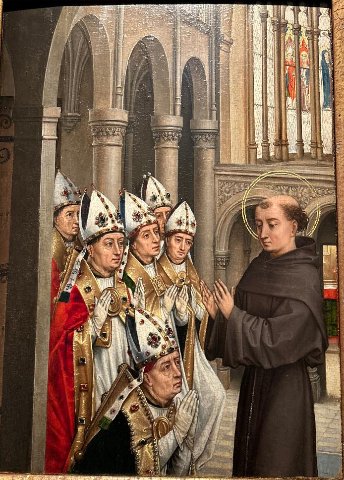

Saints and sinners are well represented. The proliferation of small pictures of saints and table top triptychs are a feature of Flemish art. There were a number of works of note. The workshop of Memling is represented by a Nativity scene. Of note are the crisply rendered folds of her garment. It was a given in these works that patrons were included in works such as the “Adoration of the Magi” as seen in a triptych by Pieter Coeke van Aelst and “Adoration of the Magi with Emperor Frederick III and Emperor Maximilian” (1510-1520) by the Master of Frankfurt.

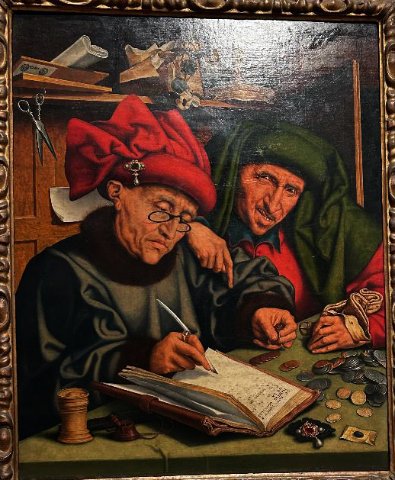

Because of the sin of usury money lending and banking was a livelihood of Jews. The Renaissance bankers of Florence found their way to circumvent this mortal sin. There was simply too much money to be made. The get out of jail fix was the story of “Render Unto Caesar” when Jesus and his followers were pressed to pay taxes. That all important passage from the New Testament was commissioned as a church fresco by Masaccio. The “Tribute Money” was created in 1425 for the Brancacci Chapel of the basilica Santa Maria del Carmine in Florence.

The stigma of the Jewish money lender persisted. “Tax Collectors” (circa 1530) by Marinus van Rymerswaele, after Quinten Matsijs, is a derivative copy and minor work. It is worth mentioning for the exaggerated anti-semitic features of one of the two “greedy” men. They hover over a table of old coins and gems.

There are a number of portraits which, for different reasons, I found of particular interest. We don’t know who is depicted in a small, detailed “Portrait of a Woman” by Catharina van Hemessen (1527/28-1567). The daughter of an artist, she created small portraits. The image is captivating. Another woman artist Catarina Ykens II (1659-1737/56), in a hexagonal frame, painted a Vanitas as a bust with scull.

It is intriguing to see the wealthy patrons of the period such as Joost Aemsz, van der Burch (1530-41) by Jan van Scorel. In an arched panel above him hover heraldic escutcheons signifying his rank and privilege. He appears to us smug and self absorbed. The irony is that to the contemporary viewer, despite the elaborate trappings, he is a relative nobody.

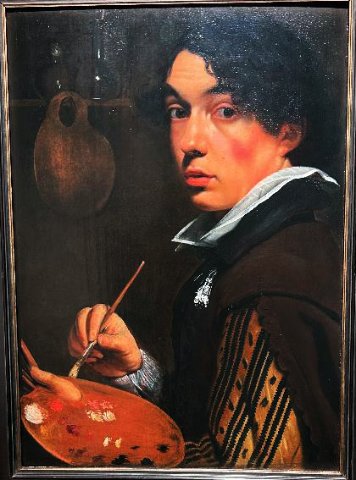

I found the self portrait of Jan Cossiers (1600-1671) to be whimsical utterly captivating. The work is beautifully executed in an Italianate manner with a soft play of light. He seems interrupted in his work and startled by an intruder. It’s an inventive moment that makes the painting less than static. In 1624 he traveled to Rome where it is likely that he viewed and was influenced by Caravaggio.

Rubens is represented with two small works, a cluttered Magi, and a genre painting. The elaborately detailed Magi may be a study for a painting to be enlarged to epic scale by the artist and his studio of assistants. The depiction of a swarthy sailor gazing at a woman with a harsh lusty expression is unique to the artist. The woman averting his attention has the typical features of his paintings. She may well be a prostitute holding out for her price.

The Jan Goessart (1478-1532) painting of “Madonna and Child” seems like a mismatch in this survey of Flemish art. The artist was one of the first who traveled and studied in Italy. The muscular, restive rendering of the child and play of light are created in the style of Mannerism.

There is an absorbing range of still life paintings on view. This was a popular and accessible category for collectors. Of particular interest is a study of tulips with other popular flowers. Curiously they were not all in season when the artist depicted them. That raises interesting questions about how that was achieved with all of the flowers in full bloom simultaneously.

In some of the works of this period the viewer is stunned by the carnage of game including deer, rabbits, peacocks and swans. In one such large work a live parrot interacts with two curious dogs at the edge of the canvas. But I was stopped dead in my tracks by a depiction of two severed boar’s heads by Jan Fyt. With snouts open revealing fangs and horns one “looks” at the other. It seems that they are engaged in posthumous conversation. Which, of course, is absurd and preposterous. It is one of the many twists that made this an adventurous visit to the museum.

The exhibition ends in an exploration of the phenomena of wunderkammer or cabinets of curiosities. In an era of global exploration and trade wealthy collectors strive to be connoisseurs of the enticing objects like ostrich eggs and tortoise shells that they acquired. Special rooms and cabinets were created to store and display their collections. The museum draws on its own rich holdings to recreate this ambiance. Salem was wealthy during the China Trade and its ephemera were acquired by the museum.

No doubt PEM was delighted to have the rare opportunity to display its stuffed Ostrich. What a nice way to underscore that the eclectic PEM grew out of the wunderkammer of wealthy Salem merchants. Indeed, it is a museum of many curiosities.