Man Up at Judi Rotenberg Gallery

Jesse Burke, El C. Leonardo, Steve Locke and Rune Olsen

By: Shawn Hill - May 02, 2010

Man Up:

Jesse Burke, El C. Leonardo, Steve Locke and Rune Olsen

Judi Rotenberg Gallery

130 Newbury St.

Judy Rotenberg Gallery

April 29—May 29, 2010

This four-man show is far from pretentious in its examination of gender identity. There's no talk about performing a role or quibbling over nature vs. culture. Instead, it's a body of evidence that supports a very simple thesis: the acting out of established male rituals in our culture is exhaustingly hard work.

Four artists might not seem like enough to give a wide-ranging diversity to the theme, but then there are so many different ways of being male in our societies. Rune Olsen's sculptures seem to reach towards a biological imperative. "Cockfight (Wall)" is just that, two birds going at it, wings flared like rapier blades, beaks gouging for eyes. Olsen's works are a kind of three dimensional drawing; he constructs the surfaces out of masking tape, and then shades the contours with charcoal. Materials are transformed by the completeness of his visions.

"Too Drunk to Fuck: Father & Son #1" and "#2" show a similar battle to the death, but this one between an older male in shorts and a kid in sweatpants and a baseball cap. The combatants go all out, the son tackling the father full-force from behind in one, the father flinging the son through the air in another. It's no-holds barred, but it's somehow presented as inevitable, an Oedipal and generational battle endemic to human nature.

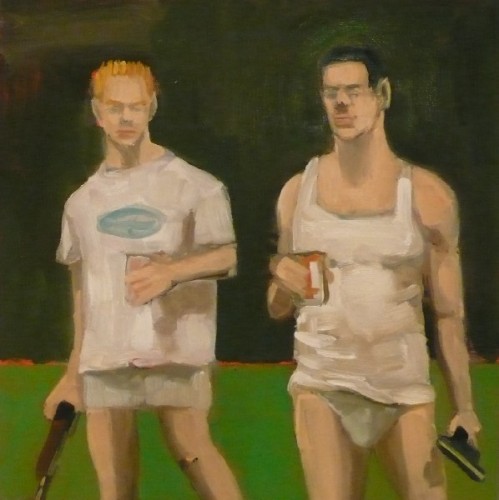

Steve Locke's lush, small gestural paintings take a different approach to gender. His boys may be drunk, and they're not fucking, but a palpable sexuality exudes from their fleshy, partially clad bodies. "shooters" shows two young men in underwear and t-shirts, holding rifles in one hand and beers in cans in another. The party is on! In "wayne," a young man in a Superman shirt sticks out his tongue, and it’s a long, pink and serpentine one .

Jesse Burke's c-prints include landscapes and still-lifes, but all the subject matter leads back to a few narrow fields of male expression: hunting, drinking, and sports. "Warren Courts" shows an empty concrete basketball rectangle at night, eerily and serenely standing attention under spotlights. Though silent and abandoned, it seems secure that its minimal accommodations will attract warm bodies any minute now.

Burke studies the surprisingly whimsical patterns of camouflage clothing in close-ups of fabric, and then pulls back to show a "Young Buck" Bambi-type dead and bleeding on the fallen autumn leaves.

But most compelling of all are his portraits, which reveal the traces (not really scars, more like stains) of macho behavior patterns. "Gladiator" is covered in mud, his white shirt and face soaked in liquid brown. You can almost hear his barrel chest gulping for air. "Nectar Imperial, Nils" is covered in liquid, and he also seems breathless, exhaling in his wet track jacket. Is the moisture his sweat or spilled beer? In "Lewellyn's Blood," the young man has closed his eyes, as if to avoid seeing the red blood stains on his shoulders. The stains in "Post Game" are the kind that are painted on, black smudges under the eyes of the buzz-cut athlete. Expressionless, he simply stands, the stubble on his face bristling with beads of sweat.

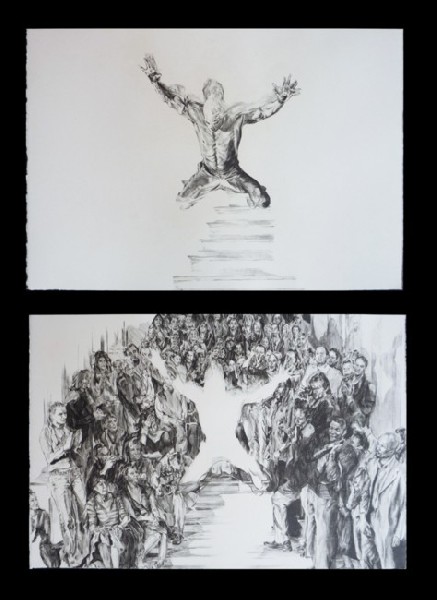

But if those guys are going for it, and taxing their bodies manfully, they've got nothing on "The Invisible Man." This mythical figure stars in a video loop by El C. Leonardo and is some sort of masked wrestler. Repeatedly, he batters himself everything but senseless on a red mat in front of an adoring audience. His physique is perfect, his skin smooth, his identity hidden but his machismo is on full display. He'd probably go all out if he only had an opponent other than himself.

A meticulous pencil drawing adds to the myth, as the wrestler flies through the air in one panel, while in the second he's a void of white that has vanished before the eyes of his adoring throng. His absence as much as his imposing presence both serve to demonstrate the fleeting nature and fetishistic attraction of a manly demeanor.

On a sad note, this is the penultimate show at Judi Rotenberg Gallery. The owner is moving into private curatorial projects, and the gallery director and manager are decamping for New York at the beginning of the summer. The gallery is a long-time Newbury St. fixture that has been committed to showing increasingly edgy and provocative work by emerging artists in recent years, and will leave a void on the street.