Bartok's Concerto for Orchestra

Performing a Great Work

By: Gerald Elias - May 03, 2013

Roland Tapley, Alfred Krips, Harry Dickson, George Zazofsky, Clarence Knudsen, Laszlo Nagy, Eugene Lehner, George Humphrey, Misha Nieland, Henry Portnoi, John Barwicki, James Pappoutsakis, Pasquale Cardillo, Bernard Zighera, Charlie Smith. What do these 15 men have in common? They were all musicians in the Boston Symphony who, with some 80 of their colleagues, performed the premiere of Béla Bartók’s Concerto for Orchestra on Friday afternoon, Dec. 1, 1944, at a concert that began at 2:30 p.m. More important for me, they were still members of the orchestra when I joined in 1975 as a 22-year-old kid. Other musicians at the premiere who I knew on either a professional or personal basis but who had retired between 1944 and 1975 included former concertmaster Richard Burgin, Rafael Hillyer, Gaston Dufresne, Louis Speyer, Rosario Mazzeo, and Roger Voisin.

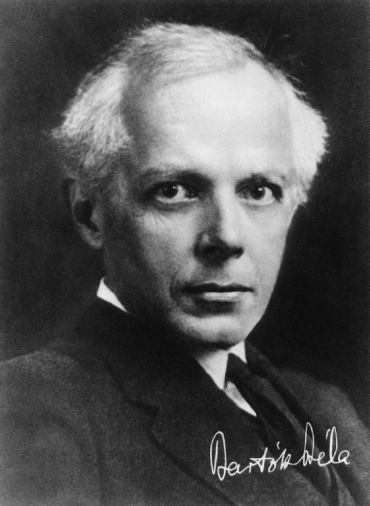

Béla Bartók

The first time I performed the Concerto for Orchestra I was moonlighting on last stand of the second violins in the New Haven Symphony. The New Haven Symphony has a long and respectable history as a semi-professional orchestra with many fine musicians. The gig also enabled me to pick up a few bucks for my Yale tuition. (FYI, my stand partner in the New Haven Symphony was future concertmaster Hall of Famer and my former stand partner in the Utah Symphony, Ralph Matson.) For me, learning the Bartók part – yes, even the second violin part in this piece is virtuoso – was a bitch, and the rehearsals were as pleasant as root canals sans Novocain. The changes in rhythms and meters were baffling, and the notes went by at an alarmingly fast rate, even in slow practice. At the performance, during the snare drummer’s beguiling solo at the beginning of the second movement, the oboist’s chair collapsed with the report of a gunshot, bringing the concert to a momentary standstill. While an effort was underway to determine whether the oboist was still alive – he was – the audience buzzed, recognizing instantly that the crash was probably not part of the drummer’s solo. My recollection is that that was the highlight of that particular performance.

The next time around for me was on Aug. 20, 1976, at which point I was a 23-year-old member of the Boston Symphony. The guest conductor was Jorge Mester, a competent if not always inspiring conductor, and the performance took place at Tanglewood where there are but two rehearsals in preparation for a concert. Having recalled what had transpired in New Haven only a couple years before, I anticipated the experience with trepidation, but miracle of miracles, from the moment of the first downbeat of the first rehearsal it was as if a “Go” switch had been turned on. All those knotty Hungarian rhythmic puzzles sounded so…natural! I was just carried along by the current of orchestra and enjoyed the ride from beginning to end. I would go as far as to speculate that Maestro Mester felt the same way. I have no doubt that orchestras like Chicago or Cleveland perform the Concerto for Orchestra equally well, but there was something very special about the way the BSO played it—there was a certain assurance that the piece was being played the way it was meant to be, and they knew it.

Concerto for Orchestra was commissioned by Serge Koussevitzky, music director of the Boston Symphony. By 1943 Bartók had been a fugitive from the war in Europe. Seriously ill, unhappy, and not terribly well-known in his adopted home in America, he was reinvigorated by the commission. It was performed no fewer than 48 times by the BSO under the baton of 11 different conductors from 1944, the year of its premiere, to the time I arrived on the scene 32 years later. Since then the BSO has played the piece at least another 59 times. My own most memorable performance was with Maestro Sir Georg Solti for a pension fund concert in 1979. Solti, who was born in Budapest and studied with Bartók, infused the music with so much folk energy I felt that I was part Hungarian peasant.

The Concerto for Orchestra along with Stravinsky’s Rite of Spring are arguably the two greatest symphonic works of the 20th century. It is rich with folk melodies and dance rhythms reminiscent of Hungary; at times dazzlingly brilliant, at others shadowy and mysterious. The Elegy still gives me the creeps, and I always need to look over my shoulder to make sure a vampire isn’t about to sink his fangs into my neck. Bartók calls the piece a concerto rather than a symphony because, as he states, “The title of this symphony-like orchestral work is explained by its tendency to treat the single instruments or instrument groups in a ‘concertant’ or soloistic manner.” That’s putting it very modestly. From the piccolo on down to the double bass every instrument, including that snare drum, is featured as a soloist, creating as rich a palette of orchestral color as can be found in the symphonic repertoire. Though in the music there is always the unmistakable feeling of his longing for his homeland, Bartók, flush with the success of the Concerto, was inspired to compose more great music, including the Sonata for Solo Violin and the Concerto for Viola, in his remaining few years of life.

For me that first performance at Tanglewood in 1976 was a game-changer not just because I had the opportunity to play this spectacular piece with a great orchestra, but because it was perhaps the first time I recognized the power of musical DNA.

This is what I mean by musical DNA: Bartók himself attended the rehearsals for the premiere of the Concerto for Orchestra. (Legend has it that Bartók, who was incredibly fussy about tempo markings and dynamics, made so many specific suggestions from the balcony that Maestro Koussevitzky had to politely request that it would be preferable to talk things over backstage.) Decades later I then had the opportunity to perform the Concerto for Orchestra sitting beside those 15 colleagues who were there at those rehearsals and performances, plus all those other musicians who had joined in the interim and had performed the piece four dozen times. That means I’ve been blessed with the inherited genes of this music; you could say I’m the second generation of musicians with a direct link to the source. I’m not suggesting this gives me any special ability to play or conduct it – it’s still no piece of cake for me to play the violin part (especially the infamous second-to-last page, which makes orchestral string players shudder), and conducting it for the first time this month will be the greatest challenge I’ve ever had on the podium. Rather, by having had the good fortune of performing the Concerto for Orchestra with the ensemble for which it was composed, the gift of this unique insight does give me a heightened sense of responsibility to keep that particular cultural history alive and well.

Why is this important? One of the many disturbing things with the situation of symphony orchestras these days is that this all-important chain of musical DNA is in danger of being broken. Boards and managements who attempt to fit a square peg into a round hole by artificially manipulating an orchestra into a corporate business model, and whose vision extends only to the bottom line, are disrupting the generational transmission. Orchestra sizes are being reduced; seasons are shortened so fewer programs are performed; salaries are being slashed, leading many great musicians to seek employment elsewhere, or simply retire; programs are being standardized into a limited number of warhorses or pops concerts, minimizing the ability of orchestras to maintain traditions, let alone create new ones. Failure becomes a self-fulfilling prophecy. And what happens when the DNA of an organism is irretrievably disrupted? Mutations, perhaps. Or extinction. We’ve seen both on the symphonic front on an alarmingly increasing basis.

Gerald Elias

Yes, conductors are able to convey a sense of what the music is about – at least some of them can – but conductors can only do so much, and they come and go. Many guest conductors are with an orchestra for only a week and they’re gone – no time there to make an enduring impression. Some excellent music directors spend quite a few years with an orchestra, leaving a legacy of achievement and an orchestra that can carry on at an extraordinarily high level. But sooner or later, music directors depart, and all that’s left are the musicians – their hands, their brains, their ears and their hearts – to pass along the musical DNA. It’s only when there is continuity and stability within an orchestra for years on end that an audience truly is able to get what it deserves: a memorable performance. I was the fortunate beneficiary of such an environment on Aug. 20, 1976, and as guest conductor of the Salt Lake Symphony on April 20, 2013, it was my goal to bring to the performance of the Concerto for Orchestra the same thrill enjoyed by an audience in Boston on Dec. 1, 1944.

Republication is with the permission of www.reichelrecommends.com