The 2012 Whitney Biennial

Ennui of the New

By: Charles Giuliano - May 04, 2012

The Whitney Biennial 2012

Curated by Elisabeth Sussman and Jay Sanders

The Whitney Museum of American Art

March 1 to May 27, 2012

The Artists: Kai Althoff, Thom Andersen, Charles Atlas, Lutz Bacher, Forrest Bess (by Robert Gober), Michael Clark, Cameron Crawford, Moyra Davey, Liz Deschenes, Nathaniel Dorsky, Nicole Eisenman, Kevin Jerome Everson, Vincent Fecteau, Andrea Fraser, LaToya Ruby Frazier, Vincent Gallo, K8 Hardy, Richard Hawkins, Werner Herzog, Jerome Hiler, Matt Hoyt, Dawn Kasper, Mike Kelley, John Kelsey, John Knight, Jutta Koether, George Kuchar, Laida Lertxundi, Kate Levant, Sam Lewitt, Joanna Malinowska, Andrew Masullo, Nick Mauss, Richard Maxwell, Sarah Michelson, Alicia Hall Moran and Jason Moran, Laura Poitras, Matt Porterfield, Luther Price, Lucy Raven, The Red Krayola, Kelly Reichardt, Elaine Reichek, Michael Robinson, Georgia Sagri, Michael E. Smith, Tom Thayer, Wu Tsang, Oscar Tuazon, Gisèle Vienne (Dennis Cooper, Stephen O'Malley, Peter Rehberg), Frederick Wiseman

Half-life, abbreviated t½, is the period of time it takes for the amount of a substance undergoing decay to decrease by half. The name was originally used to describe a characteristic of unstable atoms (radioactive decay), but it may apply to any quantity which follows a set rate of decay.

The notion of Half-life is useful to describe the experience of visiting The 2012 Whitney Biennial organized by Elisabeth Sussman and Jay Sanders.

There is an ersatz radioactivity evoked by direct channeling and absorption of sensual impressions while perambulating the space on four floors of the Marcel Breuer (1966) designed building on Madison Avenue.

Initially, it is vivid and arguably overwhelming. Although less than in prior incarnations. Recalling as recently as just two years ago then working back in increments. It was established in 1932 as the Whitney Annual and has been a biennial since 1973. Before the evolution to a Biennial there was a phase when the Annuals alternated between painting and sculpture. Not that long ago there was an agenda for curators, particularly when there were several, to tour major national arts centers and undertake studio visits.

Under former director David Ross the Biennial was opened to non American citizens with roots in the United States. It is when we first saw Gabriel Orozco, for example. Another strategy was to have a team of outside curators who acted by committee to bring a broad range of experience and sensibilities.

Taken as a whole that sweep or swath of exhibitions should comprise a running commentary on what has been new and exciting about American art. Since the 1960s, when I first became seriously, and then professionally involved with contemporary art, I have attempted to acquire all of the catalogues. At first they were thin and generic. With time they have become elaborate and conceptual, a work of art documenting works of art. A kind of stand alone or sidebar commentary of the aesthetic process of our time.

To leaf through these catalogues there is a leitmotif of keeping track of the curatorial hits and misses. There is the inevitably score keeping of artists who endured and became a part of the pantheon of modernism and post modernism. As well as those flashes in the pan whom time has tested and proven to be less than durable. There are many artists whose most notable highlight has been to be included in one of those Whitney surveys.

There have been Biennials capturing the zeitgeist like a glowing bug in a bottle. Often these were the projects evoking the most mordant venom. Where are you Robert Hughes or Hilton Kramer when we need you? There are also off peak Biennials when nothing in particular appears to be percolating. Ho hum Biennials, like, oh well, this one.

For emerging artists Inclusion in a Biennial often is the first step down the slippery slope of obsolescence. Or, now and then long overdue recognition of artists at mid, or late career. Perhaps, as this time, deceased.

There is a parallel discourse focused on artists now valued who fell off the radar screen of the Whitney’s allegedly hip and prescient curators, tastemakers, theorists and trend setters.

Whole genres of artists are deemed in or out of favor. The current version, for example, is noted for its indifference to any but the most puerile approaches to painting and sculpture. So, this time, painters need not apply or having not been considered, sui generis, have ready excuses and instant mollification for not being considered.

That phenomenon of the king/ painting is dead, long live the king is addressed obliquely in David Joselit's catalogue essay "Painting Travesty." It is a subject he appears to be revisiting evoking the ICA exhibition "Endgame" he and Sussman were involved with some years ago under director David Ross. He covers the debating points but the tone is academic, arid, erudite and not perticularly passionate to the medium.

His text bridges from Leon Battista Alberti's "foundational treatise of 1435 'On Painting'" and a dash of Jasques-Louis David's The Lictors Bringing the Bodies of His Sons (1789). Then spins forward through Aleksandr Rodchenko, a cut back to Antoine Watteau with a sidebar connection to Florine Stettheimer (another ICA show), then a bit of Wahol's Death and Disaster with a tumble into his Flowers.

All of which to set the stage for Travesty. "The first definition of travesty in the Oxford English Dictionary is: 'Dressed so as to be made ridiculous; burlesqued.' " And more.

Which is a complex approach to saying in 2012 "The king/ painting is dead." Didn't Duchamp say more economically in the second decade of the 20th century that painting is "too retinal?"

Of course numerous artists with distinguished careers have never been acknowledged by the series of Whitney exhibitions.

There are the gender, race, and sexual persuasion police who like to bust Biennials on the matter of inclusion or exclusion. New York Magazine's Jerry Saltz reports that “It’s also sad that, after half the 2010 show’s art was by women, this one is back down to the typical thirtysomething percent.”

Why on earth is that relevant? Unless the populist critic is pandering to his avid Facebook friends. He routinely gets tons of likes and comments when posting gender related topics.

A Biennial is a survey of trends in contemporary art not Noah's Arc.

This is the Biennial most noted for having so few works, generously installed. No clutter this time. And the entire fourth floor was emptied out for a series of performances. There seems to be the usual glut of film and video requiring days to see it all.

Critics have been unanimous in stating that one must see the Biennial over numerous visits fully to comprehend its depth and range.

Which leaves me out, and perhaps recuses me from writing about this project. We only had time for a single afternoon visit during a densely scheduled week in New York. We allotted one museum per day leaving energy for evening theatre.

Much has been made of the performance aspect of the project particularly as it was not farmed out off site. This Biennal, as Whitney director Adam Weinberg notes in an informative catalogue dialogue, is notable for being all under one roof. He also discusses how future Biennials will change with the relocation to the new Whitney being constructed in the Meat Market near the High Line.

When Breuer designed the iconic Madison Avenue building, performance was not one of the considerations. Its stone floors, as Weinberg notes, have been unforgiving to dancers. Film/ video have been shown in makeshift spaces. The new Whitney will have a black box theatre which is also adaptable for performances as well as a theatre/ lecture hall.

This Biennial represents both innovation as well as the end of an era in a space that has struggled to keep up with what’s new in art and museology.

It has been a couple of weeks since visiting the Whitney for a fun filled afternoon. Using a Half Life analogy that charged, radioactive experience is rapidly fading. Vivid impressions focus on the more aggressive or strident experiences. Memory, particularly at my age, is not kind to ephemera.

One hopes to be reminded of work by reading the catalogue. This rarely is helpful. The text and images are put to bed months before the exhibition is installed. Since the catalogue functions as an historical document, one would prefer for it to appear shortly after the opening. And it should include installation shots that go with the essays. Publication schedules make that impossible. But how about exploring online puublication? In this era it would make sense for the Biennial to have an interactive, updated website, and, good grief how obvious, an app.

In that sense this is not a very hip or media savvy, interactive Biennial.

Take for example the huge, bombastic, noisy, conventional, multiscreen installation, which everyone seems to love, by Werner Herzog.

It gets a lot of ink in the New York Times review by Roberta Smith. “Finally, there’s Werner Herzog’s ravishing multiscreen projection of the landscapes of the almost totally unknown sixteenth-century artist Hercules Segers, set to a Handel aria. In the catalogue Herzog notes that these Van Gogh–like images are “windows that have been pushed open for us … as if aliens had come upon us in the form of a strange visitation.”

She must have discussed it over dinner with her husband Mr. Saltz who echoes her opinion. Note that they both use the same adjective “Ravishing.” Great minds think alike. “Another filmmaker who stands out is Werner Herzog, who contributes “Hearsay of the Soul,” a ravishing five-screen digital projection, to his first-ever art show. An unexpected celebration of the handmade by the technological — and a kind of collage — it combines greatly magnified close-ups of the voluptuous landscape etchings of the Dutch artist Hercules Segers (1589-1638), whom Herzog considers “the father of modernity in art,” with some justification. The shifting scroll-like play of images is set to sonorous music, primarily by the Dutch cellist and composer Ernst Reijseger, who also appears briefly on screen, playing his heart out. I dare you not to cry.”

No Jerry you big baby. I double dare you. I shed not so much as a tear. A bit of ironic bathos, perhaps, induced by that grimacing cellist and those poorly projected blow ups of the tiny Seghers images. Which, by the way, I was not seeing for the first time.

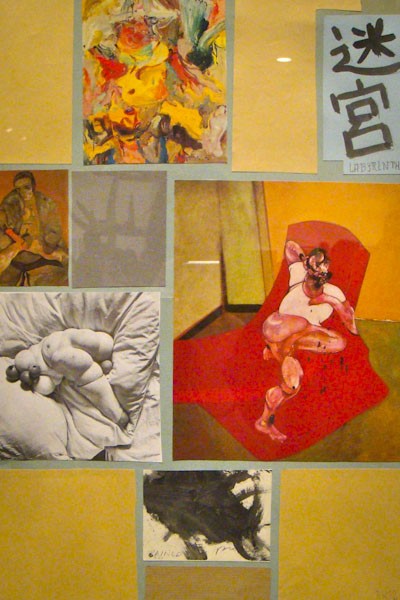

The Herzog installation was so loud that it dominated the adjoining gallery which must annoy the hell out of the artists displayed in that space. Not that the work was particularly worth looking at. Like all that wall space devoted to the nothing collages by Richard Hawkins. There seems to be no there there.

Which is precisely why this Biennial will be remembered for its inclusion of a mini exhibition within the exhibition curated by Robert Gober. It was a surprise and shock to encounter a few small, intensely precious, modernist abstractions by Forrest Bess (October 5, 1911 – November 10, 1977). He was a painter, fisherman, visionary, and eccentric. Bess was represented by Betty Parson who pursued a similar sensibility in her own rarely exhibited work. They remind me of Arthur Dove via Paul Klee. It is unusual to encounter work of real and lasting value in a Biennial which is mostly about the smoke and mirrors of fresh fever.

The hitch, in this case is a gonzo twist. It seems that Bess had perhaps psychotic sexual theories. Bending over a vitrine, if one is so inclined, you may read his notes and examine a small photograph documenting a self mutilated attempt to become a hermaphrodite. For what reason and advantage one may only imagine. Not surprisingly, Parsons, a very reserved and proper Bennington graduate, demurred from showing that aspect of his scientific/ creative work.

In a very different manner it was gender bending that proved to be so absorbing in the installation and multiscreen video “Wildness” by Wu Tsang. The environment conveys the tacky, hard scrabble sleaze of a club that features performances by Chicano drag queens. One felt completely absorbed by their issues and concerns.

By now everyone knows that bad art is really good art. What makes it good, should you encounter it in the Whitney, is that being there makes you look harder. Unlike encountering bad art in galleries where, more often than not, it is just bad art. This Biennial, not surprisingly, had a surfeit of such turgid experiences.

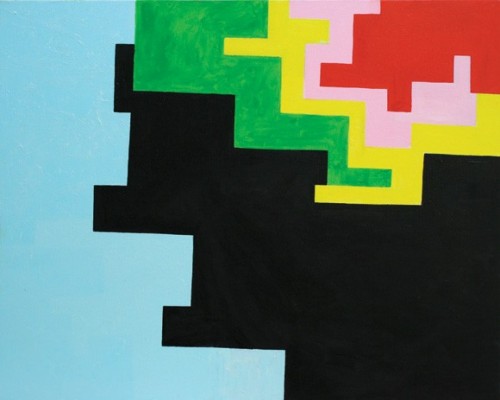

For me there was nothing remotely interesting about the numerous, colorful, small, abstract paintings of Andrew Masullo.

It’s a tougher call with the primitive representational painting of “Horse Nation” by Leonard Peltier. The work was actually presented as a project by Joanna Malinowska. It had been experienced in a similar manner as a project for the Aldrich Museum exhibition No Reservations: Native American History and Culture in Contemporary Art curated by Richard Klein in 2006.

Leonard Peltier (born September 12, 1944) is a Native American activist and member of the American Indian Movement (AIM). In 1977 he was convicted and sentenced to two consecutive terms of life imprisonment for first degree murder in the shooting of two FBI agents during a 1975 conflict on the Pine Ridge Indian Reservation.

There was however no context encountering his work at the Whitney.

And, to borrow a thought from Mr. Saltz, too many years ago Jimmy Durham was the last Native American artist I recall being shown in a Whitney Biennial.

Handpainted film is hardly unique. Consider the restorations of vintage films by Georges Méliès in Hugo. But the works by Luther Price were wonderfully intriguing and evocative.

Dawn Kasper is reported to be residing with her detritus and making art on site at the Whitney. But she took the afternoon off during our visit so her work just looked like, well, a room full of stuff. Haven’t we seen that before?

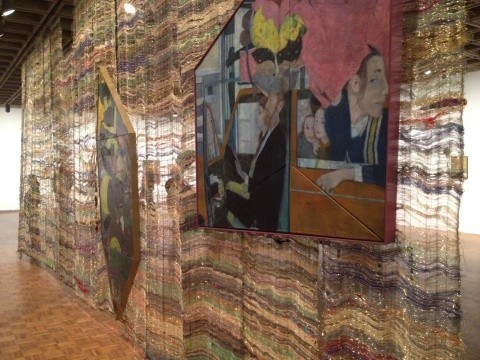

Kai Althoff continues to be intriguing and unpredictable. Here he is represented by a gossamer curtain that divides the space in an evocative manner.

When we hit the performance space on the Fourth Floor an enormous video of dance by the company of the late Merce Cunningham was being projected. It made me recall seeing the company at Jacob’s Pillow during the weekend he passed away.

We kind of came up empty on the performance aspect of this Biennial. And only sampled the videos. During three days at Okwui Enwezor's documenta 11 in 2002 we devoted one full day just to see videos. Even that just scratched the surface. Our time in NY, as noted, was more limited.

Having seen the paintings of Nicole Eisenman on other occasions I have never been a fan. But I disliked these primitivist portraits/ heads even more intensively. A couple of Boston artists I ran into, Anne Neely and Liz Awalt, argued their case for her work over coffee at Starbucks. They mostly appreciated that there was at least some painting in the Biennial. I felt that even less would be a lot more.

We engaged in a lively discussion about how perhaps the curators are smart and we are not. That, if you don’t get it, well, we are just stupid and provincial.

But I don’t think so.

Most of the established New York critics liked this Biennial. There was an interesting argument that it looked handmade by actual artists and not created by teams of studio assistants or fabricators in China or India. There were few or any big time artists. This Biennial appears to exist outside the margins of the mainstream art world.

Weinberg argued that in the past Biennials were produced in house by a team of staff curators. That changed under former director David Ross. But Weinberg’s formula is to retain a Whitney curator working with one or more outside curators. In his view, this maintains an institutional continuity while allowing for a fresh, expanded vision.

Under the old system, Whitney curators were heavily lobbied. That didn’t appear to be the case this time. The next curator or team will be announced months after the current Biennial closes and is evaluated. In reality curators only have a year compared to the norm of two to five years for most special exhibitions. It is usual for the next Biennial to react to the current one. But given the tight time frame is that really possible? By comparison a director/ curator has five years to develop a documenta project.

Now there are so many Biennials that there is aesthetic overkill. It is surely challenging for the Whitney Biennial to remain relevant.

2012 is billed as the outsider, low tech, funky, remaking of the Biennial. Yet again reinventing itself. But giving lots of space to mediocre work makes it look, well, even more mediocre.

In which case why Werner Herzog? The curious explanation is that he is an art world outsider. Celebrating another outsider, Seghers.

Don’t bother trying to make sense of all this.

In a couple of years we will have forgotten this Biennial. Just in time to have a tabula rasa for the next one.

Inclusion in a Whitney Biennial has the ability to launch the career of an artist. Will that hold true this time?

It may be a hard on visitors, but imagine how tough it is for artists to have been in the last Biennial? "In the future, everyone will be world-famous for 15 minutes."

The clock is ticking for the class of 2012.

The melt down is happening in real time.

Bell, book, and candle.