The Birds of James Audubon

New York Historical Society Exhibits Watercolors

By: Richard Friswell - May 04, 2013

John James Audubon (1785-1851) was not the first person to attempt to paint and describe all the birds of America, but for half-a-century he was the young country’s dominant wildlife artist. His seminal Birds of America (1827-39), a collection of 435 life-size prints, quickly eclipsed others’ work and remains a standard against which ornithological renditions that followed are measured. A man of his times, he reflected the surging interest in moving science out of the realm of theological debate, as it endeavored to create taxonomic models for newly-discovered creatures in a rapidly-expanding natural world. With one foot in the arts and the other in the natural sciences, Audubon defies ready characterization. With his eye very much affixed to his future place in history, his gifts as poet, writer and documentarian, he strived to actively engage his audiences in the drama and inherent beauty to be found in the birds he so actively observed, researched and documented with his brilliant, dynamic images. artes fine arts magazine

His legacy, in the form of the entire collection of watercolors made by Audubon in preparation for his monumental publication, are now owned by the New York Historical Society. Purchased by subscription from his widow, Lucy Bakewell Audubon, during difficult times surrounding the Civil War, a portion of the works is now on display in the second floor galleries of the Manhattan-based Society. More than a chronology of many of the now-familiar images, themselves, the exhibition offers a rare glimpse into the evolution of Audubon’s strategy for capturing the balletic movements of his subjects—frozen in time and place—while seemingly locked in combat, feeding their young, courting, attacking and being attacked, nesting under shrubs and in precarious cliff side homes, and, as often, staring wide-eyed out at the viewer, as if to query: why all the interest? These original renderings show all of Audubon’s experimentation with mark-making, choice of medium (pastel, eventually migrating to watercolor), and startling examples in his own hand, of methods for pinning dead specimens to his “position board” to achieve life-like poses.

Those who follow Audubon’s work are fully aware of the fact that he was not principally a field artist, but shot and arranged his material in the studio; but the reality is brought home in dramatic ways was the exhibition illustrates the process in its nascent phase. The New York Historical Society’s show, by Roberta J. M. Olson, curator of drawings at the historical society, and main author of the comprehensive exhibition catalog, is to be presented in its entirety over the next two years. Through a careful interpretation of the wealth of material available from their permanent collection and a handful of materials on loan she reveals, in Audubon, a devoté of nature and art. Over the course of his career he evolves—together with his subject matter—as though the survivalist nature and combativeness of the birds were a reflection of Audubon’s own relentless determination and—by extension—that of the emerging, rough-hewn American character, itself.

Audubon was born in Saint Domingue (now Haiti), the illegitimate son of a French sea captain and plantation owner and his French mistress. Early on, he was raised by his stepmother, Mrs. Audubon, in Nantes, France, and took a lively interest in birds, nature, drawing, and music. In 1803, at the age of 18, he was sent to America, in part to escape conscription into the Emperor Napoleon’s army. He lived on the family-owned estate at Mill Grove, near Philadelphia, where he hunted, studied and drew birds, and met his wife, Lucy Bakewell. While there, he conducted the first known bird-banding experiment in North America, tying strings around the legs of Eastern Phoebes; he learned that the birds returned to the very same nesting sites each year.

The earliest drawings on view at the exhibit—in pastel and graphite—show lifeless birds hung on a board by string tied to their legs. As the curator pointed out, this represented an effort to move away from the formal artificiality of dead game in Dutch still lifes. Audubon wrote that he desired “to shew their every position [and] in this Manner I made some pretty fair sign Boards for Poulterers.” During these same years of experimentation, he sketched birds in the wild, shooting thousands over the course of his career to allow detailed poses on his “position board” in the studio. One observer recalled an early Audubon effort to capture the ‘natural look’ of a 28-pound wild turkey he was working on in his studio: “Audubon pinned it up beside the wall to sketch and he spent several days sketching it. The damned fellow kept it pinned up there till it rotted and stunk — I hated to lose so much good eating.”

During a visit to Philadelphia in 1812 following Congress’ declaration of war with Great Britain, Audubon became an American citizen and gave up his French citizenship. After his return to Kentucky, he found that rats had eaten his entire collection of more than 200 drawings. After weeks of depression, he took to the field again, determined to re-do his drawings to an even higher standard.

The War of 1812 upset Audubon’s plans to move his business to New Orleans. He formed a partnership with Lucy’s brother and built up their trade in Henderson. Between 1812 and the Panic of 1819, times were good. Audubon bought land and slaves, founded a flour mill, and enjoyed his growing family. After 1819, Audubon went bankrupt and was thrown into jail for debt. The little money he earned was from drawing portraits, particularly death-bed sketches, greatly esteemed by country folk before photography. He wrote, “[M]y heart was sorely heavy, for scarcely had I enough to keep my dear ones alive; and yet through these dark days I was being led to the development of the talents I loved.”

Audubon spent more than a decade in business, eventually traveling down the Ohio River to western Kentucky—then the frontier—and setting up a dry-goods store in Henderson. He continued to draw birds as a hobby, amassing an impressive portfolio. While in Kentucky, Lucy gave birth to two sons, Victor Gifford and John Woodhouse, as well as a daughter who died in infancy. Audubon was quite successful in business for a while, but hard times hit, and in 1819 he was briefly jailed for bankruptcy.

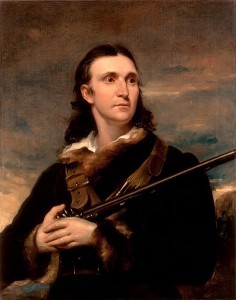

With no other prospects, Audubon set off on his epic quest to depict America’s avifauna, with nothing but his gun, artist’s materials, and a young assistant. Floating down the Mississippi, he cut an image as the classic American woodsman, living a rugged hand-to-mouth existence in the South while Lucy earned money as a tutor to wealthy plantation families.

At age 41, and with his wife’s support, Audubon took his growing collection of work to England. He sailed from New Orleans to Liverpool on the cotton hauling ship “Delos”, reaching England in the autumn of 1826, with a portfolio of over 300 drawings. With letters of introduction to prominent Englishmen, Audubon gained their quick attention. “I have been received here in a manner not to be expected during my highest enthusiastic hopes.” “The American Woodsman” was literally an overnight success. Charmed by his colorful buckskin apparel and flamboyant explorer’s demeanor, Audubon embodied for Europeans the noble Natty Bumppo in James Fenimore Cooper’s The Pioneers (1823). His life-size, highly dramatic bird portraits, along with his embellished descriptions of wilderness life, hit just the right note at the height of the Continent’s Romantic era. Audubon found a printer for the Birds of America, first in Edinburgh, then London, and later collaborated with the Scottish ornithologist William MacGillivray on the Ornithological Biographies – life histories of each of the species in the work.

The exhibit is hung chronologically. The first large image is that of the Wild Turkey. Audubon believed, like Benjamin Franklin, that the Wild Turkey (Meleagris gallopavo, Havell, plate 1 [1825])—and the first released publically—should serve as the national symbol for America, believing it to be more “moral” than the rapacious “Bird of Washington.” Audubon believed the “White Headed Eagle” was too aggressive to symbolize the newly-founded republic. Toward that end, this conviction is exemplified in his portrayal of the Bald Eagle (from piebald, meaning spotty or patchy) in one of his earliest renderings. He portrayed the Bald Eagle devouring a Canada goose, until he later determined, upon dissection, that the feathers in the eagle’s gut were most likely the result of preening, not feeding. A later version, reworked to be more behaviorally accurate, has the eagle feasting on a bloated catfish, next to the discarded entrails of a small fish head. The many revisions of ‘Eagle’ illustrates Audubon’s obsessive eye for detail and traits displayed in nature—becoming a vital part of his intimate connection to his subject and a reflection of his belief that, “[T]he reason why my works pleased him [J. B. Kidd, Edinburgh] was because they are all exact copies of the works of God.”

Another example of Audubon’s precision-driven methodology—where careful observational records go beyond the bounds of mere pictorial representations, to capture the subtlest habits and patterns of his birds—can be found in his rendering of the Great Blue Heron (Ardea herodius, Havell pl. 211, 1821; 1834). Presented in life-size format, the image, itself, stands thirty-six inches tall. The figure of the heron is seen dipping its long neck and extended beak toward some unseen prey near the water’s edge. The pin feathers, crown and wings akimbo are all splayed in various directions, yet appear in perfect balance. Massive clawed feet tread the muddy soil, partially obscured by sea grass, thus heightening the observational ‘feel’ for the viewer. This often staid and motionless figure, seen in marshes throughout the world, seems alive with bound-up energy and purpose. About this scene, he wrote: “…The tread of the tall bird…no one hears, so carefully does he place his foot on the moist ground…Now his golden eye glances over the surrounding objects, in surveying which he takes advantage of the full stretch of his graceful neck. Satisfied that no danger is near, he…patiently awaits the approach of his finned prey.” This excerpt from his carefully-detailed observation reveals a true naturalist’s instincts; one who later translates his methodical notes into a startlingly-dramatic interpretation of his subject with graphite and water color..

Brought to life through a process of pinning a dead specimen to a board, Audubon succeeds in animating nature in ways rarely observed—and perhaps in largely fanciful ways. Daring renditions of gravity-defying tumbles, aerial battles fought at treetop level and outlandish contortions of neck, torso and wings, all mange to transcend the realm of the believable—creating a new and more fantastical reality in the process. Scenes of murderous aggression are presented next to pastoral tranquility. Evidence of intelligence, resourcefulness, socialization and wide-ranging appetites for all forms of earth-bound creatures reveal careful attention to the habits, as well as the appearance for Audubon’s birds. These scrupulous observations (always subject to revision in later field notes and renderings) allowed for the most dramatic and authentic detailing of America’s birds, then or since.

The Historical Society’s exhibition is hung in groupings of five images, known as fascicles (one large, single bird, one medium and three smaller prints, showing birds in flocks). Prints were sold by subscription and would have been delivered by mail, the entire series spread out over 12 years—later to be bound into volumes. But these groups were gathered with no taxonomic or species-specific objective in mind, other than to demonstrate the wide ranging variety of bird life all around us. The gallery exhibit is arranged in order of their release, allowing the visitor to the show to react to the range of colors, configuration and quality these birds must have generated for Audubon’s wealthy patrons. At the center of the far wall of the main hall is the prized Double-Elephant folio (self-published between 1826 and 1838, Robert Havell & Son, London). Only about 120 copies of the book are known to exist in the world. Printed on ‘double-elephant’-sized paper—nearly 40″ high, by 27 ” wide and the largest available at the time—Audubon specifically selected these dimensions so that the birds appearing as hand-colored prints in the book, like those on the walls of the gallery, could be portrayed life size. Carefully protested by a large display case, the Society’s Birds of America volume sits open to a sample page, to be turned to a new image weekly.

But, for as much as the massive volume is a national treasure and a bibliophilic rarity that is exciting to see, the real excitement rests with the collection of drawings themselves. One has to remind oneself that these are not prints on view, but the original renderings of the artist, himself. Evidence of trial-and-error are to found, along with clear evidence of Audubon’s evolution in technique and overarching ambition as a evolving naturalist, print maker and public personality dealing with international success (as well as hardship and failure).

“I have lost nothing,” Audubon says in lines used for the catalog’s epigraph, “in exchanging the pleasure of studying men for that of admiring the feathered race.”

The last print was issued in 1838, by which time Audubon had achieved fame and a modest degree of comfort, traveled this country several more times in search of birds, and settled in New York City. He made one more trip out West in 1843, the basis for his final work of mammals, the Viviparous Quadrupeds of North America, which was largely completed by his sons and the text of which was written by his long-time friend, the Lutheran pastor John Bachman (whose daughters married Audubon’s sons). Audubon spent his last years in senility and died at age 65. He is buried in the Trinity Cemetery at 155th Street and Broadway in New York City.

Part 1 of “Audubon’s Aviary: The Complete Flock” runs through May 19, 2013. Parts 2 and 3 will be shown in 2014 and 2015.

The New-York Historical Society, 170 Central Park West, at 77th Street. (212) 873-3400,

Visit the site at: www.nyhistory.org

The New York Historical Society, a preeminent educational and research institution, is home to both New York City’s oldest museum and one of the nation’s most distinguished independent research libraries.

The Society is dedicated to presenting exhibitions and public programs, and fostering research that reveal the dynamism of history and its influence on the world of today. Founded in 1804, its holdings cover four centuries of American history, and include one of the world’s greatest collections of historical artifacts, American art and other materials documenting the history of the United States as seen through the prism of New York City and State.

Forty thousand of the Society’s most treasured pieces are on permanent display in the Henry Luce III Center for the Study of American Culture, and a self-guided audio tour brings these artifacts to life with anecdotes and stories.

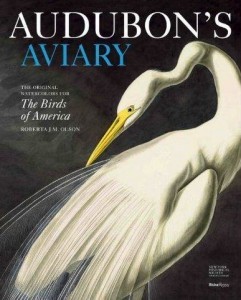

Audubon’s Aviary: The Original Watercolors for the ‘Birds of America’

Item # 34223

Price: $59.95

Member price: $53.96

Order catalogue at http://www.nyhistorystore.com

Written by Roberta J.M. Olson with a contribution by Marjorie Shelley, Audubon’s Aviary: The Original Watercolors for the ‘Birds of America’ (one of Amazon.com’s 2012 Best Books of the Year) returns to these original paintings and tells the story behind this monumental classic with new discoveries about this American icon, as well as fresh insights and engaging quotes from Audubon’s own compelling writings. These powerful images-all newly photographed using state-of-the-art techniques-illuminate Audubon’s genius, which linked natural history, art, and a respect for the environment. This volume reproduces for the first time all 474 Audubon avian watercolors in the collection of the New-York Historical Society, and contains 710 illustrations, including many with the birds life-size as they were originally rendered by Audubon.

Reposted courtesy of Richard Friswell and Artes Magazine.