Route of the Maya: Part Three

Guatemala City, Lake Atitlan and Its Mayan Towns

By: Zeren Earls - May 04, 2016

Traveling on the Mayan trade route after crossing the border from Honduras to Guatemala, we stopped by a health clinic run by the Guatemalan government. We spoke with the nurses who, in addition to caring for walk-in patients, provided free shots to all children under the age of five. A major problem they shared with us was child pregnancy in girls aged 10-14. The official marrying age for girls used to be 14; now it is 18. Men go to jail if they marry under-age girls.

On the way to Guatemala City we stopped at Kaminaljuyu, a strategically located city dating from pre-classical times (1000 BC). Due to the city’s proximity to sources of obsidian (volcanic glass) and jade, it once controlled the routes for trade in those goods as well as in shells, feathers, cacao, and salt, with the Pacific Coast and Northern Highlands. What is left of the city’s ruins are now within the Kaminaljuyu Archeological Park, also visited by present-day Mayans as a sacred site for prayer and altar offerings to the ancestors.

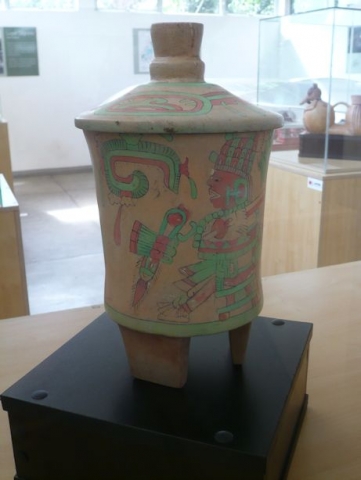

Starting at the Kaminaljuyu museum, we viewed image maps of the city and ceramic objects such as vessels used for burial offerings found inside mounds. Examples of altar offerings employed in the sacred fire included elements of Mayan cosmology such as cinnamon, chocolate, pine resin, and candles. Replicas of obsidian artifacts were a sampling of blades, arrow heads, and knives used in daily and ritual life.

Pre-classical buildings (1000 BC-400 AD) were constructed over clay platforms and supported a thatched roof. Early classical architecture (400-650 AD) utilized pumice stone held together with a clay mix. Large stones replaced pumice later on and some of the earlier structures were buried underground to make room above for ball courts. Since the 1960 s, archaeologists from the Carnegie Institution of Washington, Pennsylvania State University and Japan have excavated different mounds.

Following a walkabout amidst the ruins, we mingled with the locals, observing them praying around their sacred fires, while children climbed trees or played on the grass. Some families had traveled three hours by bus to arrive at the sacred site.

As we continued on the trade route a panoramic view of Guatemala City, spread on a broad plain surrounded by hills and a backdrop of volcanoes, emerged before our eyes. An overturned truck on the road delayed our arrival in the capital city, which is divided into 14 zones, number one being the historic center. Finally we disembarked at the Stofella Hotel in Zone 10 for a restful night, in preparation for the next day’s immersion in Guatemala City, which I had visited in the late 80s.

Guatemala has the largest indigenous population of all Central American countries. Of the country’s 16 million people, 50% are indigenous. Those who speak one of the 23 Amerindian languages and wear traditional clothing are considered Maya; the colors of a woman’s blouse indicate where she is from. Native Maya who wear western-style clothing are called Ladinos; most others are mestiza (mixed race), with a small percentage of people of direct Spanish origin.

Of metropolitan Guatemala City’s 5 million population, 3 million crowd the city proper. Our morning tour began in one of the city’s poorest neighborhoods, where most adults and children are illiterate due to extreme poverty, even though the Maya had obtained the right to education in 1996. A local school here, assisted by a non-profit organisation, works with children and young adults between the ages of 2 and 21. Unfortunately we could not visit the school, as our tour fell on a Saturday.

Driving by the dump in the same neighborhood, we observed people trying to make a living by picking through trash. Some 3500 people above the age of 14 have permits to enter the dump to pick up bottles and plastic in order to scrape a living by selling them for recycling, as they are all mixed with trash collected by trucks. All the workers are Maya; many eat the food they find here. Those without a permit go through what is left on the sidewalk. Average monthly income in the country is $325; 1.5 million Guatemalans work abroad and send money home, generating the country’s number one source of income.

Today’s Guatemala City exemplifies an expanding developing capital, as opposed to my visit 30 years ago. Although colonial decor adorns the whole city, fast modernization is evident everywhere. The Civic Center boasts modern architectural complexes, many of which are government buildings. The facades and walls of some are decorated with bas-relief murals by artist Roberto González Goyri. They depict the history of Guatemala, from the arrival of the Spaniards to the conquest to the union of Maya and Spaniards, creating a mestizo nation.

The Metropolitan Cathedral is the centerpiece of the Old Town in Zone 1. It faces the Central Park, where people feed pigeons gathering by the fountain, vendors hawk their wares, and people dance to a live band on stage. During our stroll through the park, we encountered street artists making chalk drawings on the pavement, as well as people demonstrating against corruption at every level of government. Placards asked about the whereabouts of the 45,000 people, 5000 of whom were children, who had disappeared during the 36-year civil war (1956-1990). Although a monument of two hands holding up a dove, erected at the end of the civil war, commemorates peace, the sorrow of the war still lingers; candles are lit at night in the park in remembrance.

In the morning we departed for Panajachel, stopping along the way at small towns to observe local customs and visit artisans. It was market day in Santa Apolonia. Multi colored umbrellas providing shade for vendors stretched as far as the eye could see. Tomatoes and strawberries in baskets and bundled greens spread on the ground vied for attention. Embroidered blouses, belts, and hand-woven textiles on makeshift stalls added to the riot of color. Mothers with babies strapped on their backs and shoppers with bundles on their heads created indelible images.

Next door the Catholic Church was all draped in purple and white in anticipation of Holy Week, a time when Guatemala solemnly commemorates the passion and death of Christ. The faithful arrived for Sunday service, for which women’s attire included a hand-woven shawl, huipil and corte (traditional indigenous blouse and skirt). Following the service, a statue of the Madonna was carried out of the church to be taken to homes for blessing upon request.

Santa Apolonia is famous for its earthenware pottery. We visited the workshop of an old woman who had been making pots since childhood. On her outdoor patio, we watched her work with red clay from nearby hills, using both her hands and her feet. Stooping over the broken stones of her patio, she shaped her pot, after which she used crude instruments for surface decoration – her creativity surged beyond her limited economic and material means.

To our luck, we happened upon the Conquest Festival in town. In Guatemala the beginning of the Spanish conquest in 1524 is a celebratory occasion, as it led to the joining of two different races and religions to form a new nation. The festival, celebrated in different towns throughout the year, features locals wearing masks and costumes in a Conquest Dance, which also includes parades, processions, and live bands playing folk music.

After a lunch stop in Tecpán, we continued to Sololá, one of Guatemala’s largest Mayan cities. Soon after we arrived, I was so charmed by the vibrant heaps of clothing sold by equally colorful locals along the road that I could not resist buying a black huipil with multi colored embroidery. Another highlight for me was the cemetery in this highland town, with its brightly colored tombs lining narrow alleys, which led to views of the volcanoes over Lake Atitlán in the distance. Our day ended with a boat ride across the lake to Panajachel. It was dusk when we arrived at our lakeside hotel, the Porta Hotel Del Lago, to yet another stunning view of the volcanoes at sunset.

In the morning we traveled by boat to lakeside towns, as there is no road circling the lake; Lake Atitlán is named after the town of Atitlán, which means ‘Place of Ample Water’. This cruise was another opportunity to view the beautiful lake, which was formed by a volcanic explosion more than 85,000 years ago and is towered over by the volcanoes of San Pedro, Tolimán, and Atitlán.

Picture-book views during the cruise included women doing laundry along the shore and fishermen casting nets in the distance. Upon disembarking in the town of Santiago Atitlán, we were met by locals in native wear unique to the region. Women wore on their heads the typical xocop, made of a long strip of red wool with designs that coils around the head like a snake, symbolizing fertility. Men wore colorful woven short pants, in line with the fishing tradition.

The Church of Saint James the Apostle, like churches in other towns, was bedecked in purple and white for Holy Week. The church has special significance for the locals, as it provided shelter for them during the civil war. The Guatemalan military massacred many of the town’s people and assassinated the Catholic pastor, whose heart is buried in the church.

In a chapel next to the church is the altar to Maximón, a deity who is a mixture of a Mayan idol and a Catholic semi-saint. He is made of bundles of material and a wooden mask, and wears a hat. A shaman guards him from morning till dawn for one year, after which another shaman takes over. Maximón joins the Christian celebrations during Holy Week.

The tradition of Mayan textiles, with their distinctive geometric patterns and symbols, is passed on to the Santiago community by a family of weavers, whom we visited. The entire family – father, mother, daughter, and son – were weavers and trained others in the community. We watched the father at the loom and the mother as she prepared yarn, and listened to the son talk about the traditional black-patterned red shirt worn by men. Following our delightful visit, which included the presence of a pet parrot, we returned to our boat in anticipation of our visit to the next lakeside village.

Upon arrival in San Antonio Palopo, we enjoyed a lunch of grilled fish with steamed vegetables at a restaurant overlooking the lake. Thereafter a visit to the home of local weavers revealed the process of extracting dyes from natural sources such as avocado seed and tree bark. We watched women weave at back-strap looms. All the women in the house wore traditional indigo-colored blouses and a blue-and-purple braided fabric ornament over their long hair. Mayan women have long hair; cut hair is a sign of punishment. Returning to Panajachel, I spent the rest of the afternoon at the hotel with a restful view of the lake and the volcanoes.

In the morning we journeyed overland, enjoying the countryside with its waterfalls and terraced hills along the Pan-American Highway to Antigua. We stopped at a garage in El Tejar to see old school buses imported from the US, which had been converted to passenger buses with rearranged seats and added luggage racks and repainted. The transformation under skilled hands was amazing.

A visit to a family that makes roof tiles and bricks was an insight into the labor-intensive ways of producing basic building materials. Creating mud out of a pile of dirt, the father shaped floor tiles by putting the mud into a large square wood frame, leveling it and leaving it to dry. Meanwhile, another family member made roof tiles by shaping them around a curved mold. Their daily production was 300 tiles each. Against a backdrop of laundry hanging over the dirt pile, the children played nearby.

With my empathy level raised many times over, we continued on our way to Antigua.

(To be continued)