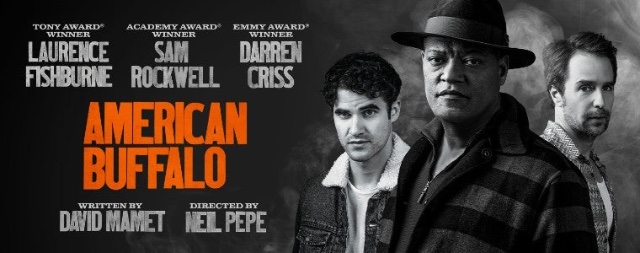

American Buffalo by David Mamet

Nick Pepe Makes the Play Live

By: Susan Hall - May 04, 2022

American Buffalo, David Mamet’s great play, is running on Broadway now with a stellar cast. Laurence Fishburne, Sam Rockwell and Darren Criss give us Donny, Teach and Bobby, pacing the thrust stage chock full of junk like pieces of junk themselves. Bobby is a junkie. All three men have a false belief that they can alter the downward trajectory of their lives.

Mamet speaks about the poetry of his language. It comes very much from the lower end. Next to John Millington Synge, also up now at the Irish Repertory Theatre, we get opposite ends of the poetry of theatrical language. Synge. while rooted in the soil and the language of tramps and tinkers, is lilting and lovely, yet words reveal the miserable circumstances of its characters.

Mamet’s language is rough and dirty, yet it is also poetry. The concentric circles formed by the dialogue of the characters circle around the notions of ‘business’, ‘friendship’ and ‘betrayal.” They spiral on through the day and into the night as a heist is planned. You can't turn off or away from "Lookit, sir, if I could get a hold of some of that stuff you were interested in, would you be interested in some of it?"

Scott Pask creates a set which exudes junk, covering the floor, jamming into the first row of audiences' seats and hanging from a frame-like ceiling. Tyler Micoleau lights to reveal the worn details of hockey sticks and kitchenware. Lights also are the curtain when they go black.

Costumes created by Dede Ayite have a subtle differences. Teach's hat, which he has misplaced, is a search line from beginning to end. He finally makes a hat out of newspaper, recalling Elizabeth Bishop's poem about Ezra Pound in the ward of an insane asylum: "This is a Jew in a newspaper hat that dances weeping down the ward" and then joyfully dancing down the ward, dancing carefully down the ward -- all in the house of Bedlam." Certainly the heart of "American Buffalo" is close to madness driven by repeated failures and dashed hopes.

The heist is junk too. The two men and the boy are looking for an American Buffalo nickel, which is probably worth no more than five cents and maybe less. Nearby on the Gold coast of Chicago, Lake Shore Drive, heists are also taking place.They are called "business." If their perpetrators are caught, a Judge will assess their sentence as already served by the pain caused them as they endured the judicial processes. They will go free. The trio in American Buffalo probably will not.

This production is directed by Nick Pepe of the Atlantic Theater. He says that he often had the good sense to let these brilliant actors go their own way. Winding up and down the set, turning to and from the surrounding audience, there is a natural movement to the action. We barely notice Teach pick up an iron as he moves through the detritus. His hand, however, will remember this action.

Each of the onstage characters has a unique voice and presentation of language. The language of the street must arrest. The necessity of quick, tumbling delivery comes with Teach. Bobby is slow-witted, immobilized, his lines delivered in a flat, muted, staccato. He crescendos when he is pinned in a lie, but maintains the inflexible, no-affect talk.

Don is sometimes discussed as the top of a three generation family-like group, but here he and Teach are about the same age. Occasionally we get the punchy jewels "action talks, bullshit walks." Don's diction is clearly different from the others. He may be street smart, but he is also kindly and soft, and his feeling for the young Bob is expressed with warmth. When he carefully listens to Teach rail against Fletch, the "Godot" of this play, He is an offstage character who is going to pull this heist off and who doesn't show up.

Teach is a stark contrast to Don. He is less driven by mania, than by a need to express not just every thought but every word that crosses his mind in no matter what order. This leads to some of the most brilliant and familiar lines in the play: The syntactical frenzy of "They treat me like an asshole. They are an asshole." "Only, and I am telling you this, Don. Only, and I am not, I don't think, casting anything on anyone: from the mouth of the Southern bull dyke asshole ingrate of a vicious nowhere cunt can this trash come." Teach often delivers his lines as an aria. Don and Bob are left to recitative. There is no common time between the three voices, and this excites the ear and mind.

Nothing is stale or withered about the play and the operatic take on the language, the crossing of the three voices, adds to its impact. Rockwell has gale force as Teach, Fishburne's is emotionally rich, and the young actor Patrick Andrews playing Bob is terrifyingly brittle, almost inarticulate.

Directed by Neil Pepe. Set, Scott Pask; costumes, Dede Ayite; lighting, Tyler Micoleau. About 1 hour 40 minutes. Through July 10 at Circle in the Square, 235 W. 50th St., New York. telecharge.com.