Charles Giuliano Retrospective at New England School of Art & Design at Suffolk University

Surveying Thirty Years of Photographs

By: Charles Giuliano - May 07, 2007

"Charles Giuliano: Last Call; A Retrospective"

May 18 through June 28

Opening reception, Friday, May 18, 5 to 8 PM

75 Arlington Street

Boston, Mass. 02116

Hours: Monday through Saturday, 9 to 6 pm

Weekends enter through St. James Avenue

Over the past several months, in addition to packing and moving from Boston to the Berkshires, I have been digging through thounsands of slides and negatives. Using Photo Shop a selection of these images have been scanned and archived. They were originally shot to illustrate articles for newspapers and magazines, more recently to post to online websites, and as slides for art history classes. The initial intent and function of this photography was journalistic and educational. So there was always a more pragmatic than aesthetic aspect to the work.

A selection of 130 digital prints, 13x19." in editions of 25, are included in the exhibition "Charles Giuliano: Last Call, a Retrospective" on view from May 18 through June 28 in the gallery of the New England School of Art & Design at Suffolk University. A reception will be held on Friday, May 18 from 5 to 7 pm at 75 Arlington Street. The exhibition will be installed by James Manning who is taking over as acting director of the program.

Ironically, I came to photography indirectly. As a studio major at Brandeis University, at the time, photography was not included in the curriculum. Even in art history courses photography was never considered. As a teenager, I made photographs and received a Polaroid camera as a Christmas present. But film proved to be expensive and although you coated the pictures with a sealer the images were fugitive.

During the 60s, while living in New York, I hung out with photographers and photo reps. A gang of us decided to act like paparazzi and scam our way into the Cheetah a huge disco near Times Square. Just so I could get in they loaned me a camera and loaded it with film. The idea was that at the end of the night we would collect all the film, develop it, try to sell prints and pool the profits. Not much came of it but they told me my pictures were pretty good and since the camera was old just let me keep it. So that got me into the Cheetah on a regular basis as well as back stage to hang with musicians.

One night, Curtis Knight, the leader of a funky soul band called "The Flames" told us to be up front during their set because "I'm going to turn Jimi loose." They went through their usual tunes until Curtis nodded to Jimi who started to play guitar with his teeth, behind his back, over his head, rubbing the neck back and forth on the mike stand, or playing into the amps for feedback. We shot lots of pictures and back stage Jimi told us that he could use some publicity pictures. Gerry Berkery, my mentor at the time, printed and mounted our shots and we went off to his flea bag hotel. The front desk called him. Jimi came and we exchanged the pictures. We shook hands and, to this day, I recall how limp and fishy it was. Off stage he was quiet and shy compared to an outrageous persona while performing.

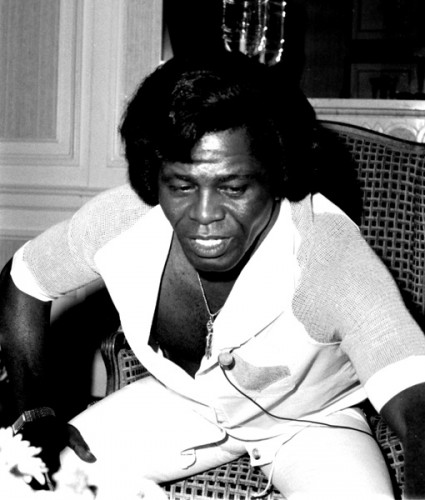

We went up town to the Apollo and shot James Brown. After an acid trip Gerry freaked out and I visited him in Bellevue. We lost touch after that and my camera got ripped off while I was watching a movie. I didn't have the money to replace it. When banging on a bong while staring at a lava lamp with an artist friend, Gerry Sherman, he was playing a new record. It was the Jimi Hendrix Experience. It all sounded familiar and I stared at the cover. Could this be the same dude I knew as Jimmy James with Curtis Knight? A lot had happened since those funky days at the Cheetah. All those negatives I shot of Jimi and James Brown stayed in the pool and for a time that was the end of my paparazzi career.

By 1968, I was back in Boston via New Orleans and hooked up as a writer and later editor of the underground newspaper The Avatar. By default, I became the designer for a few issues while we were feuding with the Fort Hill, Mel Lyman zealots. We put out some terrific issues under enormous adversity including Issue Number 25 which the Hill stole and sold for scrap. I have a couple of copies with my I Ching design on the cover. That limited experience got me a brief job as design director for Boston After Dark (now the Phoenix) but I was soon fired for incompetence and stayed on as art critic. I had a weekly column Art Bag and played a hand in promoting the tiny art scene including the first open studios event The Studio Coalition which evolved into the Boston Visual Artists Union. As an activist I pressured the Museum of Fine Arts to show contemporary art and Perry T. Rathbone, the director at the time, called to personally tell me that because of my relentless pressure (and the guerilla Smart Ducky show "Flush with the Walls" held briefly in the basement men's room) he was hiring Kenworth Moffett as the curator of 20th century art.

By then I was the jazz and rock critic for the Boston Herald Traveler. I inherited the gig when a boyhood friend, Timothy Crouse, left for Rolling Stone. He wrote the famous book "Boys on the Bus." I learned to cover pop music from the seat of my pants. What I knew came from hanging out with musicians like Elton John, Captain Beefheart, and Miles Davis. You couldn't ask for better mentors.

Unfortunately, during the Herald days, when I had incredible access to musicians, I wasn't taking photographs. The Herald had staff to do that and Jimmy Carlson was my go to guy. He shot the Newport Jazz Festival riots which I scooped for the front page of the Herald. But the bastards at the city desk didn't give me a byline even though I broke the story. Seems that arts writers didn't get credit for news stories.

When the Herald folded, in 1971, days after a Supreme Court Decision in which they lost their TV station, we were all out of a gig. The paper got sold to Hearst's Record American. I spent the next year collecting checks and reading through World War Two. When I went bust I started driving a hack for Town Taxi and free lancing for a bunch of local rags including the Boston Ledger, What's New, The Paper, and eventually the daily Patriot Ledger. I went to Boston University for art history and moonlighted in the rock scene including working at Sandy's Jazz Revival in Beverly. Sandy was a piece of work.

As a freelancer there was a need to provide pictures for the stories. Somehow I got a Minolta, and then another, and a telephoto lens. The light meter never worked but I got good at figuring out the exposure. One summer I took a darkroom class with Jim Haberman and used to develop and print in the basement of the old New England School of Art and Design on Newbury Street. In clubs I shot with available light pushing Tri X one or two stops. Although it was expensive I started to shoot some color rolling my own film and developing using the E 6 process. When traveling to Europe I rolled about a hundred cassettes of film to shoot in the Louvre and it took months to process, mount, and label all those slides. Eventually the slide and negative library filled eight, four drawer, file cabinets.

Now, ironically, all that material is obsolete. A couple of years ago I bought a Nikon digital camera. Digital is the way to go and in a fraction of time I can do things that were never possible in the dark room. But purists, for whom photography is more a fetish than art form, stick to film and chemistry. I was never into the romance of photography, just the hunt for great images. It was access as an arts reporter and critic that provided subject matter. I had a couple of shows of this material including the former Akin Gallery. But I didn't have control of the images. I just had the slides blown up commercially so there was no way to make changes. Now, with Photo Shop, once the slide or negative is scanned the fun begins.

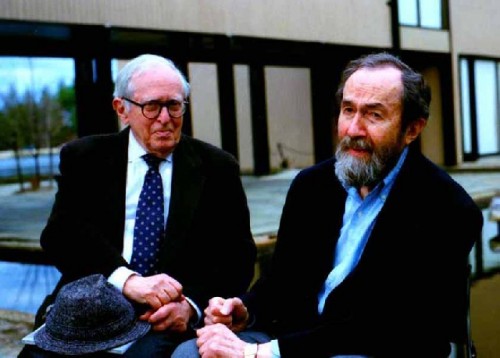

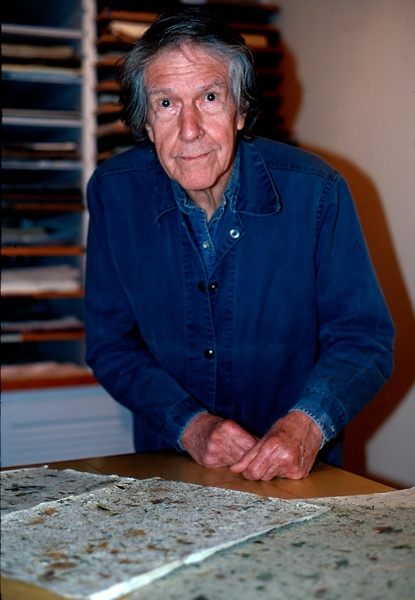

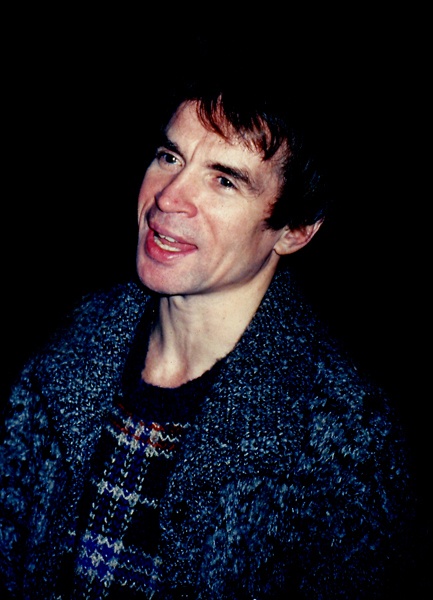

The range and quality of the material in this exhibition has been challenging. At times vintage negatives were of such poor quality that they were impossible to print in the darkroom. There was a great shot of Dennis Hopper during an interview when he was freaked out. It took immense effort to get a print out of a lost cause. Similarly, I had struggled with shots of Leonard Bernstein or a sports event that included Ted Williams, Joe DiMaggio, Bobby Orr and Willie Mays. For some performers, such as Miles Davis, I had lots of material to select from, while with others there might be a couple of decent shots. During an interview with composer Philip Glass he said "Charles I can't talk to your camera." The interview is long forgotten but the images are timeless.

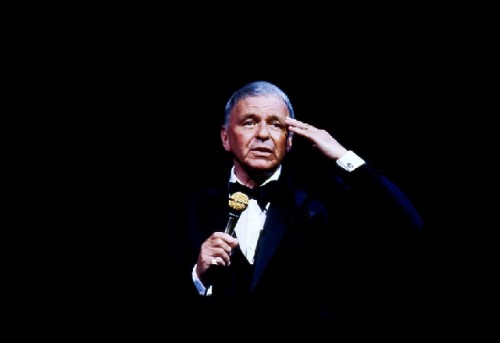

On another occasion at the old Music Hall, now Wang Center, I was in the second row snapping away at Frank Sinatra. The gang was up from Providence and I was in the middle of the Cosa Nostra section. A made guy threatened to whack me if I kept shooting. But I got great shots. Another time Paul Simon started talking to me from the stage asking why I was taking so many pictures. During a live TV group interview with Don McLean he called me an "ass hole." It was reported in the papers. Sometimes people have put their hands up to block a shot or turned their back. The director of the Boston College Museum of Art stuck her ass in my face to prevent me from photographing Francois Gilot who was a jerk anyway. Hey, it was all a part of the game.

In addition to music and arts celebrities the show includes many local artists, curators, museum directors, and gallerists as well as distinguished guest speakers at Suffolk including Maxine Hong Kingston, Anna Deavere Smith, Henry Gates and Robert Brustein. At Harvard I recently shot the artists Maya Lin and Ed Ruscha. The work continues and may be changed and edited right up to the final moments of installation. So, while a retrospective, it is still work in progress. Is it art? Well, that's not for me to say. The most important part is that you make the work and are serious about it. But putting it all together in this manner, spanning some 30 years or so, has been a remarkable and enriching experience. It is a fitting way to say goodbye to a university and arts community which I have served and covered for all these years. Later man.