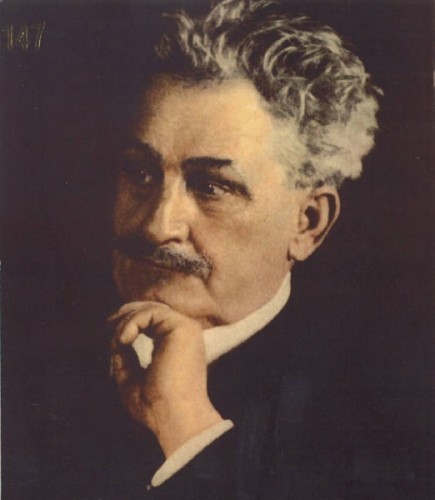

Karita Mattila in Janacek's Makropulos Case

Metropolitan Opera Offers the Elixir of Life

By: Susan Hall - May 09, 2012

The Makropulos Case

By Leos Janacek

Conducted by Jiri Belohlavek

Elijah Moshinsky, production

Anthony Ward, set design

Karita Matilla, Emilia Marty

May 8, 2012

Janacek considered The Makropulos Case one of his finest operas. After fighting for the rights, composition went smoothly. With his 70th birthday approaching, he may well have been thinking about extended life. Surely in Europe after World War I, in which 6,000,000 young men had died, the subject of life was at the front of many minds. An elixir to add a few centuries?

G.B. Shaw wrote Back to Methuselah shortly before Karel Capek wrote the Makropulos play, but apparently the choice of subject matter was coincidental. What made Shaw’s take different was the many centuries-old people lived in a Utopian community. In Makropulos, Emilia Marty stood alone. As performed by Karita Mattila, in a defining take, this is both an advantage, and finally her downfall.

Mattila gives us a human Marty, at first mysteriously desperate to get hold of papers whose content only she knows. Mattila immediately reveals the passionate, unnatural beauty of Emilia as she swoops unannounced into a law office, waving a newspaper which reports a disposition in the case of Prus v. Gregor, a case even older than Jarndyce v. Jarndyce. Dickens’ case ends with everyone laughing. Makropulos is no laughing matter. It is not about money, but rather life and death.

Only Prus does not succumb, but still he is caught in Emilia’s web. The orchestra is stilled. Marty pauses too and then asks what it will take. Prus indicates a night of pleasures. This turns out to be a night in a deep freeze, and although he feels disgusted and cheated by the froideur, Prus hands over the formula for the elixir of life Marty has sought.

Mattila shows us a woman empty of feeling until she sees herself reflected in the lives of others. When she realizes that although she is alive, she is dead inside, she burns the formula and dies before us.

Mattila’s drunken outburst at the end is terrifying and shocking. The feverish, wild music is supported by trills until the fanfare heard as a distance at the beginning of the opera comes rolling in as Marty loses control.

The infinite variety of characterization gives depth to the story. Vitek’s pitter patter of legal jargon in the law office, his repetition of the case name: Causa Gregor Prus, the chatter of the stagehands cleaning up after a performance, and the ill-fated romance of a young singer and Prus’ son, all are revealing.

The other star of the performance is the conductor Jiri Belohlavek who led the Met orchestra from the elaborate and trenchant embroidery of sound which opens the opera to the power and strength which eventually overwhelms the characters. Melodies are woven into the structure. An organic propulsion drew the performers and audience forward.

The sets are terrific. The frame is always an isosceles trapezoid. We are first in a lawyer’s office, where file cabinets extend from floor to ceiling, perhaps filled entirely with the papers of this interminable case. In the second act, we are on stage after a performance. A figure for the next opera drops down, a sphinx into which Marty nestles and displays herself. A sphinx is of course a mysterious and dreaded female figure in Greek mythology. Marty can only display its curse when she murmurs the Lord’s prayer in Greek, her native language over three hundred years ago.

The final scenes are a hotel room, in which a royal blue sofa extends almost as long as Marty’s life. And then the burning of the formula and the end of Marty. Even the green lining of Marty’s fur coat refers back to the costumes of the premier.

Janacek had written that this story was terrible. “The emotion of the individual who will never find her end. A true misery. She does not want anything. She does not want for anything…and then, what a climax. What a precipice.” Indeed.