Frank Lloyd Wright's Great Usonian Vision

The Zimmerman House in Manchester, NH

By: Mark Favermann - May 10, 2008

A Zimmerman House Tour provides visitors with a 1 ½-2 hour tour of the house: Mondays, Thursdays and Fridays at 2pm Sundays at 11:30am and 2PM. Tickets are $20 for adults, $19 for seniors, $16 for students and $8 for children over 7. No children under 7 are allowed.

Prices include general admission to the Currier Museum of Art. Reservations must be made in advance by calling 603.669.6144 x108. Tours of the Zimmerman House depart from and return to the museum by a shuttle. Each tour is limited to 12 visitors.

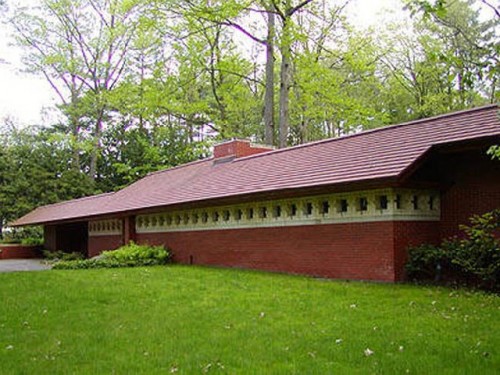

Set in a lushly tree lined, upscale neighborhood, there is a rather unique one story single-family house located in the once predominantly blue collar mill town of Manchester, New Hampshire. In the early 1950's, the house was built for a doctor and his wife, Dr. Isadore and Lucille Zimmerman. It was designed by arguably the greatest and best-known American architect of the 20th century, Frank Lloyd Wright (FLW).

Known for his flamboyance and eccentric life and loves, Wright actually dictated to his clients how they were to live in his structures. In the case of the Zimmermans, they entirely bought into his aesthetic ethos. Though exquisite, Wright never visited the house in person.

After creating debatably the greatest modernist house of the 20th Century with Falling Water in 1935 for the wealthy Kaufmann family of Pittsburgh, Wright had this notion of a democratic house for what he considered middle class people. These houses designed in a distinctly American style were to be affordable for the "common people." He called them Usonian.

FLW considered this an affordable house, for middle class people. The Zimmerman House cost $55,000 to design and build in the early 1950's. This was at a time when a comparably sized house cost around $5000. But, this particular Manchester house has all the Wright stuff.

A somewhat distorted Wright notion, this meant primarily single couples who were successful, rather sophisticated and generally included doctors, lawyers, or academics. Apparently, this work for these upper middle class clients was his bread and butter during the last decade and half of his career.

There were only about 60 of these homes ever built. Wright had claimed that he was to create 1000 or more of them. I find this number rather hard to believe since there were only about five constructed in New England. It would mean that he would have designed and somehow supervised construction of 75 to hundred small homes each year.

This would have been a daunting task for a man in his eighties and nineties, and even a man half his age, less quirky man, with the limited staff size of at Taliesen West, his massive home studio. FLW was known for his exaggeration.

Actually, after World War II, Wright designed over 350 structures of all kinds. Many never got built. Some were finished after his death like Manhattan's Guggenheim Museum. But many did. Still, this was an impressive creative outpouring of high level work in the sunset of his professional life. Wright was an American architectural phenomenon--eyernally self-promoting, boasting or otherwise. Many of the Usonian houses were quite distinctive.

No matter what the actual statistics, these houses were often quite wonderful. Wright referred to these houses as Usonia which is an abbreviation for United States of North America. Wright first conceived of them in the late 30's, but they really did not take off until the late forties and early fifties after the Depression and World War II.

An outgrowth of the flat-roofed, Prairie Style that Wright created in the earlier part of the 20th Century, both styles featured low roofs, open living areas, and made abundant use of brick, wood, and other natural materials. Usonian homes were somewhat small, rather compact, one-story structures set on concrete slabs with piping for radiant heat set beneath. Kitchens were incorporated or integrated into the living areas. To be more cost effective and aesthetically pleasing, open carports took the place of garages.

To keep down construction costs, Wright specified that Usonian style houses were primarily to be made of inexpensive concrete blocks. The concept was that the 16 inch by three-inch-thick modular blocks could be easily assembled in a variety of ways and were secured together with steel rods and grout.

Actually, Frank Lloyd Wright hoped that homebuyers would save money by building their own Usonian Automatic houses like some sort of a giant set of toy blocks. This was a naive notion: assembling the modular parts proved very complicated and therefore, most clients were forced to hire contractors to construct their Usonian houses usually at a premium.

Despite Frank Lloyd Wright's aspirations toward simplicity and economy, not surprisingly, Usonian houses often exceeded carefully thought-out budgets. This was nothing new for Wright and many of his projects. Wright's tendency for expensive details added greatly to the cost of these houses for the masses as he would have called them.

Usonian houses can be considered one of the major precedents and aesthetic genesis of the nearly ubiquitous "ranch" tract homes which were extremely popular throughout America during the 1950s and 60's. Unfortunately, most often the less talented architects and builders adapted the general horizontal shape and notion of low cost construction materials while ignoring the concepts of good aesthetics, interesting site placement and the thoughtful styling of Wright's houses.

The Zimmerman House construction was supervised by one of Wright's apprentices, John Geiger, from Taliesen West in Phoenix, Arizona. He was in constant communication with Wright's office during the building process. Apparently, the Zimmermans paid for the apprentice to live in Manchester for over a year. I wonder what he did during the cold months when construction was interrupted by inclement weather and frozen conditions?

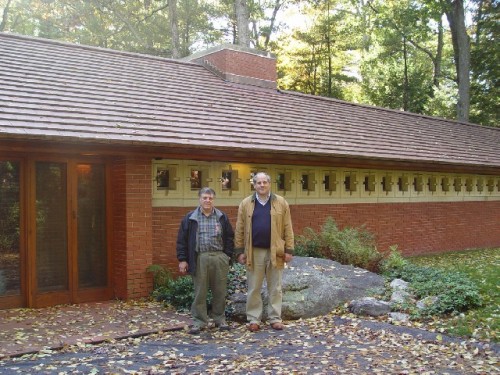

The house is set on ¾'s of an acre on a corner wooded lot. In keeping with Wright's near obsessive philosophical notion of an organic architecture, the Zimmerman House was designed for the land that it was built upon. A local surveyor measured and noted the location of trees and other natural features for Wright to base his plans on. A large bolder became the focal point from the front door.

Whenever possible, Wright chose materials drawn from nature. Wright literally believed that a good building does not hurt the landscape but actually made the landscape more beautiful than before the structure was built.

The Zimmerman House is long and low. Like all Usonian houses it is one story, has no basement or attic and features an open carport. It has concrete slab flooring, board and batten walls, built-in furniture and little ornamentation. However, it does have abundant views of nature. The siding is unglazed brick, the roof is clay tile, the woodwork is golden-hued upland Georgia cypress. The window casings are cast concrete. There is no paint used inside or outside.

The irregular slope of the roof gives the house a sculptural quality and draws the line of vision to the ground. The roof's wide eaves swoop low to reinforce this. The Zimmerman House has few ornamental details, however the sensitive use of materials visually suggests richness and a minimalist ornamentalism.

This can be seen in the small, square concrete window construction that forms an elegant visually strong band across the front facade. This is fenestration with representation. The façade also creates a sense of privacy for the people living inside the house.

In contrast, the back of the house is virtually transparent with large windows and glass doors. Apparently, Wright made one of few modifications for Mrs. Zimmerman in the rear of the house. as was his general preference, he had specified solid plate glass along the back. She insisted upon ventilation.

Eventually, casement windows were specified overlooking the garden. Window corners were also mitered to allow uninterrupted open views. This generous use of glass underscored Wright's and Modernist architectural thinking that the boundaries between indoors and outdoors should vanish.

Like other Modernists, instead of traditional interiors, FLW created open spaces that flowed into each other rather than separate rooms. A narrow entry corridor flows into the main living room area. Built-in seating faces the large back window "wall" that allows for garden views that change with the seasons and times of the day.

The integrated furniture for the Zimmerman House was created by Wright and his staff. Built-in shelves, cabinets, and seating areas minimized clutter and conserved precious space. Everything from table linens to tables and chairs were custom designed for this residential space.

It has been said that the Zimmermans consulted with Wright before they purchased a work of art or piece of ceramics. This was part of the organic whole that gave each of his houses a handcrafted feel. Talk about drinking the master's KoolAid. The Zimmerman's really bought into the Wright Philosophy.

However Wright did allow for one rather major personal Zimmerman touch in the living room area. This involved the fact that the Zimmerman's enjoyed and played music. Wright built in a table that allowed for easy rearrangement to create a space for a string quartet to perform in a rather tight space.

With its autumnal color pallet, there is a visual uniformity in the Zimmerman House. Colors, textures and even shapes create a subtle rhythm that harmonizes and visually connects all of the rooms. Overhead lighting is recessed into woodwork. A grid pattern and square shapes are repeated throughout. Also harmoniously integrated into the overall house design, the 1950 state of the art galley kitchen is efficient and quite cozy.

Dr. and Mrs. Zimmerman must have loved this Frank Lloyd Wright jewel and shared that love with their friends. Their good friend and Dr. Zimmerman's hospital colleague, Dr. Toufic Kalil, built another quite different looking Usonian house a few doors down, on the same street, five years later. This house remains in the Kalil family.

Opened only by appointment to the public, the house was left by Mrs. Zimmerman to the Currier Museum of Art. It is the only Frank Lloyd Wright designed residence open to the public in New England. Over the past several years, it has been elegantly restored by the Currier. The Zimmerman House is one of the most beautiful and pleasing of Usonian structures. It seems quite Wright.