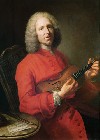

Boston Baroque's Les Indes Galantes Triumphs

Amanda Forsythe and Aaron Sheehan Shine as Vocal Soloists

By: David Bonetti - May 10, 2011

Les Indes Galantes

Music by Jean-Philippe Rameau

Libretto by Louis Fuzelier

First performance: Paris, 1735

Boston Baroque

Jordan Hall, New England Conservatory of Music

May 7, 2011

Conductor: Martin Pearlman

Stage direction: Sam Helfrich

Choreography: Marjorie Folkman

Cast: Amanda Forsythe, Aaron Sheehan, Nathalie Paulin, Sumner Thompson, Daniel Auchincloss and Nathaniel Watson in multiple roles

Dancers: Majorie Folkman, Marric Buessing, Nicole Kedaroe, Henoch Spinola, and Jessie Stinnett

How can it be that a semi-staged production on a shallow space at the lip of a stage also occupied by a fully visible orchestra trumps musically and theatrically many of the fully staged operas put on in the Boston area this season?

If you are to believe Boston Baroque music director Martin Pearlman, who in his production notes asserts that Rameau’s music is so great that it stands on its own merits and doesn’t need “the distractions of elaborate stage business,” it is because that music precedes spectacle. I don’t know if Pearlman is taking a lightly veiled swipe at the Boston Early Music Festival, which invests considerable effort and money into staging spectacular baroque operas every two years, but he is really only making excuses for his limited resources.

We go to the opera, after all, because it is spectacle as well as music. Otherwise we might as well stay home and listen to a CD. Indeed, spectacle is especially important in French Baroque opera, but Pearlman got away without it by assembling an orchestra and cast of singers and dancers who were so in sync with the music and the drama inherent in it that they made you nearly forget that an exploding volcano and an exotic Persian flower festival were in the scenario.

If only other semi-staged or concert versions of opera worked half so well! (And I include James Levine’s musically splendid but dramatically inert presentations of “Bluebeard’s Castle” and “Oedipus Rex” at Symphony Hall with the BSO this season.)

French baroque opera is a different species from the Italian-derived baroque opera that has become so popular with the opera audience over the past couple of decades. Boston is arguably the American capital of opera by Handel, who based his works on Italian precedents by composers like Alessandro Scarlatti. But there are relatively few works put on locally by his French contemporaries. Handel was born in 1685; Rameau in 1683. The French baroque has been owned by William Christie’s “Les Arts Florissants” and Marc Minkowski’s “Les Musiciens du Louvre,” which are based, not surprisingly, in France. Indeed, the score for Boston Baroque’s “Les Indes Galantes” was produced by Christie.

There are major differences between the French and Italian models. The French favors a hybrid between singing and dancing called opera-ballet, while the Italian model is more purely vocal. Indeed, French audiences expected a ballet within their operas into the 20th century, and Italian composers like Donizetti and Verdi who composed for Paris were required to include a ballet in their scores. Italian opera is divided into parts: overture, aria, recitative, ensemble, chorus, etc. French opera is more whole: the parts flow into each other without separation.

Most importantly, in French opera the music is determined by the text, the sound of the words and their syllabic patterns, while the Italian opera depends more upon pure melody, to which the more flexible Italian language is more easily set. To grossly generalize - French opera favors the words and Italian the music.

Les Indes Galantes is structured episodically. It opens with a Prologue in which Hebe, the goddess of youth, laments that the youth of Europe are more interested in the glories of war than by the pleasures of love. The goddess of Love and a flock of cupids, the dancers of the evening, are summoned and sent to exotic lands in search of pairs of true lovers.

The following four acts – or entrees – take place in Turkey, Peru, Persia and among the Indians (“sauvages”) of North America. The work displays the racism and unconscious cultural superiority of orientalism, the 18th and 19th century tendency of Europeans to both sentimentalize and infantilize non-European peoples and cultures. However, the “exotics” are shown to be superior to the Europeans in humane characteristics: The Turk is generous, the American Indian is noble, etc. But most importantly, according to the scenario, in each locale, true love is practiced.

Could Rameau, who was a friend of Voltaire, intend a political critique? By embracing the arts of war, Europe had conquered much of the world, but had it lost its capacity to be human in the process?

Pearlman founded what became Boston Baroque in 1973. He has been studying and conducting baroque music for nearly 40 years, and he knows his stuff. He led the orchestra with total confidence and brought out Rameau’s remarkable rhythms, which shift from one dance form to another, throughout. This music pulses: a gavotte gives way to a minuet, which leads to a chaconne.

In the first entrée, “The Generous Turk,” what sounds like a hornpipe leads to what American mid-westerners might call a hoe-down. Without any solo singing, the orchestra, which was rich in colorful trumpet, wind and percussion sounds as well as an onstage musette or hurdy gurdy, was a pleasure in its own right. And the chorus sang with the orchestra as if it were an instrument made up of human voices.

But what wonderful solo singing the evening provided!

Amanda Forsythe is, for good reason, Boston’s favorite singer at the moment. Her light soprano is clear, agile and technically proficient, and her tone is crystalline. She sings and acts with spirit – she is full of life. When she walked on stage in the Prologue as Hebe, goddess of youth, she embodies youth. Wearing a white pant suit and a white head band – all the costumes seem to be from the singers’ own closets – she seems to have just come straight off the tennis court. From that entrance, Forsythe owns the stage and the production, even though she appears in only three of the five parts. Her singing is never showy for its own sake – it emerges from the text to clarify the sentiment. And her movement and acting are as natural and unstilted as her singing. She is a profoundly empathetic and communicative artist.

Although their voices and styles are different, I can’t help but think of the late Lorraine Hunt Lieberson when I hear her sing. They are (were) both sexy broads capable of singing with the greatest refinement. In the Prologue there is an ode to music, in which Forsythe trills along with the orchestra imitating bird song to the accompaniment of the hurdy gurdy. It was pure heaven.

Tenor Aaron Sheehan, another Boston favorite, is Forsythe’s match. Tall and handsome, he is an elegant but game performer. When we first see him, in the first entrée, “The Generous Turk,” he is carried on to the stage by a pair of dancers and dumped on the floor. (He has just been washed up on shore from a shipwreck.) His voice is high and clear and he articulates the text with understanding. He is a charming performer. Finding his long-lost lover on the island where he has been deposited, he sings a lovely aria on their reunion.

Canadian soprano Nathalie Paulin must have been challenged to find the appropriate garments in her closet, since she appears in all but one episode of the work. In her first appearance, as the goddess L’Amour, she wears a fire-red suit and black leather high-heeled boots. In the final entrée “The Savages,” her outfit was a throwback to the ‘60s and quite hideous, but it made sense considering that the final scene, in which the Indians smoke the peace pipe with their conquerors, is turned into a hippieish pot-party. Vocally, Paulin is first-rate. She sings with a deep soulfulness and is also capable of expressing humor in her acting.

The vocal highlight of the opera was the quartet in the third entrée, “The Flowers.” Duets are very rare in baroque opera, quartets even more so. In this transcendent ensemble, which finds two separated pairs of lovers reunited, Forsythe and Paulin sing together and it was a delicious treat.

Joining them in the quartet were tenor Daniel Auchincloss and baritone Nathaniel Watson, both of whom were excellent in their own right. The sixth singer in the production, baritone Sumner Thompson, sang with great dignity and authority. As the Inca priest Huascar in the second entrée, Thompson sang an invocation to the sun with boldness and elegance. His is a deeply masculine voice with a deep and rich bottom that rises to an effortless top.

Dance is an integral part of the entertainment, and the five cupids in search of true lovers had a dance in each of the five sections of the work as well as helping out in other capacities – dumping poor Valere (Sheehan) on the shores, for instance. Choreographer Marjorie Folkman made no attempt to replicate baroque dance. Although baroque opera is popular today, the stiltled dance that accompanied it remains an acquired taste.

Folkman, who has danced with Mark Morris and Merce Cunningham, combined the formality of baroque dance with early modernism. Her lithe young performers danced barefoot. There is no toe-work, and only one lift in the entire work. The effect is sort of baroque dance as interpreted by Isadora Duncan at the Acropolis. Lots of hand motions, circle dances, and loose garments an integral part of the movement. It seemed to work perfectly with the modern-dress semi-staging. And the dancers were excellent.

Stage director Sam Helfrich showed a certain amount of wit in dealing with no space and no budget. At the start of each episode, the chorus waved contemporary flags of the country where the action transpires. And in the second entrée, when the storm at sea occurs, Emilie (Paulin) pulls out an umbrella followed soon by most of the chorus. The pot-party scene is a howl. But the flower festival is weakly suggested by single red tulips held by soloists and chorus members. And the volcano scene is a total failure. Red-orange lights projected on the stage were insufficient to evoke the earth’s explosion. I doubt if anyone in the audience knew what was happening if they hadn’t read the synopsis beforehand.

Helfrich was game to attempt as much as he did, but I wish he had done more – better coordinate the costumes, for instance. Some of them were fine, but having the men wear suits is one thing if they have Armani or Tom Ford in the closet; here there were too many ill-fitting Wearhouse for Men outfits. (Come on guys, buy a good suit! You’re performers.)

These are tiny quibbles in an evening that was a delight from start to finish. Mr. Pearlman, you are right: the music is what matters, but the visuals count too.