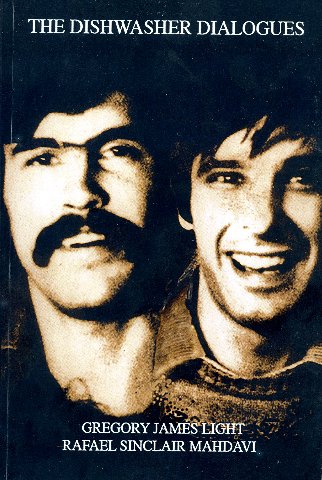

The Dishwasher Dialogues

Down and Out in Paris in the 1970s

By: Charles Giuliano - May 11, 2022

George Orwell has been described as part of the Lost Generation in Paris. His first book Down and Out in London and Paris was published in 1933.

Arriving as a young man in Paris in the 1970s the artist and writer Rafael Mahdavi may be described as part of the Get Lost generation on the lam from the Vietnam draft. Forfeiting his American passport, one of several, and all his possessions he went underground and undocumented, keeping a low profile in France.

He and Orwell had something in common. To survive they worked as plongeurs in restaurants. This is the most menial of labor. The French term means divers which in English translates as pearl diver.

It meant having your hands in soapy water through long shifts. On the lowest rung of the restaurant staff it also entailed doing odd jobs and dirty work. But you get the mornings to do creative work, explore the city and live the life. Orwell wrote and Mahdavi managed to paint and do experimental photography in a tiny space.

This latest Mahdavi book, memoirs and mysteries over the past several years, is a collaboration with writer Gregory James Light. The Dishwasher Dialogues. 2022, 255 pages, ISBN 9788423973612, $9.99 is published by Kindle and available through Amazon.

It is written in a format that resembles Q&A. The text alternates as transcribed from their dialogues. But there are no initials that identify the authors. This is done with contrasting typography. The text of one voice is slightly bolder than the other. It takes time to get the hang of it and keep track of their separate but equal comments.

Now and then they interject an overview of the ground rules which generally articulates that there really are none. They are both free to introduce any topic that comes to mind within the time-frame of working for Leroy Haynes.

Although a primary subject, and the glue that binds them, the African American restaurateur remains somewhat enigmatic. He is both friends with and supportive of staff but also somewhat distant. Though he served in the military he does not identify as American. Yet he primarily hires Americans and has a clientele of ex pats.

Jazz musicians visit for soul food and to get down with Leroy. Some famous artists come by including James Baldwin who holds court.

Leroy plays the ponies and is generous when he scores at the track. The house red flows freely and now and then, on holidays and special occasions, there is Châteaus Lafite Rothschild and Mouton-Rothschild and fine champagne. On benders Haynes can be out for days while the staff keep things running.

When a customer boisterously harassed a waitress Leroy charged, lifted him by the lapels, and tossed him to the curb. The customers stood and applauded. He was also tough on junkies and didn’t want dope at his bar. They got the word and stayed away.

With an undocumented staff the pay was minimal but came with a fine staff meal before service as well as drinks after hours. It’s enough to keep starving artists alive. On Sundays they were on their own which meant cheap Chinese or Arab food.

The authors switch off bartending which is a better job and chance to chat up the frails. At the end of the night tips were pooled and divided. Except for the plongeur. When Rafael became a bartender he lobbied to change that.

Much of this is about drugs and sex but no rock ‘n’ roll. Have you listened to French rock? It’s a rather sad story.

There is much discussion of art and theatre which is when the book most comes alive. Or sidebars into philosophy and art world politics. Everyone is remarkably well read and there is a ferment that titubates the ebb and flow of arguments. Books are given as Christmas presents.

Remembered decades on there is just a hint of the passion that once was. Those late night debates, fueled by reefer, bumps and cheap red wine were percussive. The arts boiled into a blood sport. Rafael takes no prisoners and tells it like it is.

The struggle of Light appeared to be more grave than that of Mahdavi. As a playwright of the avant-garde there was the challenge of getting work produced. Mahdavi contributed sets and designs.

An intriguing project entailed rags stained and dripped with paint. The schmatas were hung to dry on lines strung in Rafael’s small space. This stuff was smashed into plastic trash bags and with the small cast and crew conveyed by train to Edinburgh.

There they performed on the outermost fringe of the Fringe Festival. Looking out at the audience it was confirmed that a single individual attended their performance.

Leroy contributed to but never attended any of the performances or vernissages.

With a tinge of envy Gregory notes that Rafael always managed to have shows often in decent galleries. Which entailed a flow of sales. That’s true and Mahdavi remains prolific with global exhibitions.

There is poignant discussion of how, with little or no means, one manages to create. Gregory just needs paper to write. Working in small spaces Rafael only stretches canvases when they are exhibited. Rolled they are easier to transport.

He learned this lesson the hard way. Early on there was a show in another country which was crated and sent home. When Rafael went to pick it up the customs inspector wanted to charge a fortune in tax. What ensued was an epic battle. Eventually, the bureaucrat threw up his hands and relented. Rafael then opened the crates and cut the canvases off their stretchers. It was the only way to get them into his small car.

When we worked together on a show he brought the canvases rolled on a flight from Paris. The family was then living in Wellesley. We built stretchers and removed the paintings after the show. I was instructed to send them rolled in tubes with no insurance. They were listed as “tablecloths” for customs.

Oh the French. Sometimes "Liberté, Egalité, Fraternité" can get pretty fucked up.

The book is anecdotal with the appeal of a chapter related to the story being conveyed.

While embedded with Paris it is not a tour guide. The point of view is that of guys with no money trying to survive on the French equivalent of minimum wage. Chez Haynes had better food but paid about on a par with McDonald’s.

As undocumented they might have been deported at any time. Mahdavi’s ID consisted of the Paris version of a T pass which is renewed monthly. You had to be a resident to get one and it provided access to the superb transit system. As I can confirm.

It took us to the last stop from which Astrid and I walked a few blocks to have dinner with my cousin Paula, husband, and little Josef. It is rare and a great honor when Parisians entertain at home.

Years after his dishwasher days I stayed for a week in Rafael’s loft/ studio in the Marais. That’s a fine tale for another day.