Billy Budd, The Makropulos Case and Sex at the Met

Janacek and Britten Deliver the Real Goods Without Help

By: Susan Hall - May 12, 2012

All too often this year at the Metropolitan Opera, particularly in productions where General Manager Peter Gelb's heavy hand is evident, sex is imposed from without. Only Carmen evades the signature Gelb white nightie, perhaps because the very name Carmen suggests sex and black. Productions arriving from times past are mercifully Gelb-free.

In The Makropulos Case, played wonderfully by Karita Matiila, passions are elicited from any man who comes into Emilia's wake. The opera is constructed to be sexy throughout. Emilia's iciness is perceived by men only in bed. The audience gets it when they hear Emilia diffidently announce, as a young man's suicide is reported, ”Well, people kill themselves." Here a life without feeling has eroded over three hundred years. But it's still sexy.

Billy Budd, a great opera by Benjamin Britten, is another matter. After E.M. Forster came out as a homosexual, he stopped writing novels about the relationship between men and women. Yet his creative juices continued to flow. An article Forster wrote on English poet George Crabbe came to Britten's attention. The Crabbe poem, The Borough would become the basis for Peter Grimes.

Forster and Britten talked about an opera they might create together. They agreed on Melville's Billy Budd. Forster had never tried drama, and was apprehensive about his ability to pull off a libretto. The experienced Eric Crozier who had just completed Albert Herring with Britten, joined the project. In Billy Budd, the creative team wrote about homoerotic love without being sexually explicit.

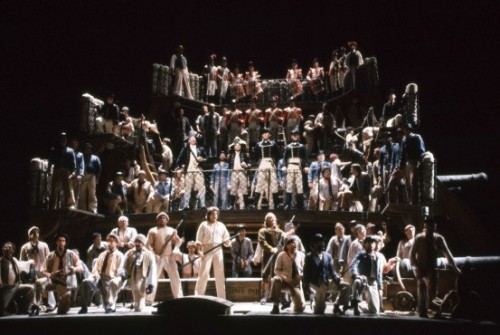

The 1978 Met production holds up remarkably well. Perhaps because the moving parts of the set work smoothly and without noise interference, the audience seemed particularly grateful. More important is the sexual take on the story. The spiritual quest and the unleashing of homoerotic love, both present in Melville's story, are presented clearly.

While no Melville expert worth his salt claims that Melville was gay, there is no question that he was in touch with same sex love in letters to the older Nathaniel Hawthorne. Polymorphous perversion, Freud's term for our natural drive to all kinds of sex, may be more comfortable for artists.

Nathan Gunn as Billy attracts attention. The adapted ballad he sings, 'Billy in the Darbies," accompanied by a chirping piccolo, is perfectly beautiful. One senses a curious satisfaction as Billy conquers the evil Claggart. Even though he pays a high price, he is able to save Vere by refusing to turn the crew against him.

Captain Vere, who sends Billy to his death even though he might save him, very clearly expresses attraction. By creating a character who is not simply authoritative, aristocratic and educated, Britten/Forster delve into Vere's salvation through the love of the handsome young sailor. That Vere is tortured by his decision makes his failure to rescue all the more poignant.

John Daszak as Vere is the star of this production. He shows the moral complexity of his dilemma. His desire for Billy, couched in terms of spiritual beauty, reveals homoerotic desire. Daszak's voice has just the right touch of squillo and comfortably rode over the orchestra.

David Robertson led the Met Orchestra to display all of Britten's enticing variety. From the string passages alternating between B minor and major at the opening, written to suggest the moral ambiguity, Robertson captures Britten's tonal variety. Unfortunately, in some sections of the house, the orchestra drowned out Gunn and Morris.

The Met chorus was terrific, from the moment they sing "Blow her away to Hilo" early on, to the inarticulate grunts, a powerful comment on a senseless hanging.

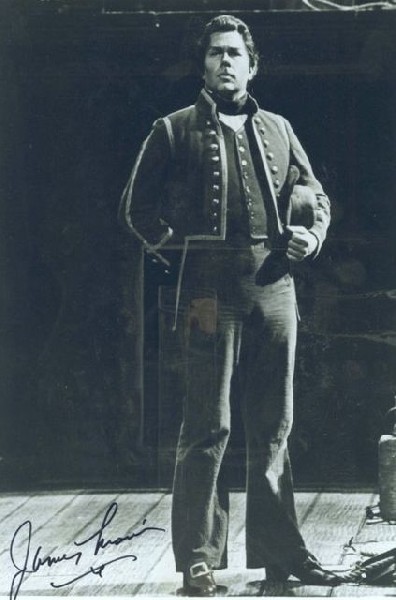

James Morris was Claggart in the Met's premier of this production. He steers away from Billy's attractions. His take was pretty straight evil, except for an aria in which he expresses, as Forster wrote, "...passion, love constricted, perverted, poisoned, but nonetheless flowing down this agonized channel, a sexual discharge gone evil."

Billy Budd is a rare work in which beauty enchants and also elevates with Vere's conversion. Interestingly, both Forster and Britten found destruction more interesting. Forster in his short story, The Other Boat, and Britten in his last opera, Death in Venice.

This production comes from a time when focus was on the live productions in the house. The artistic director of the English National Opera recently commenting on the possibilities of HDs, said that his entire focus was on mounting a live production. He doesn’t have time for HDs. Nor does he think they build audiences, new or old. There's the kind of artistic director you want in an opera house. Let movie makers go to Hollywood.