Charles Giuliano's Honky Art

A 1968 Sketch Book

By: Charles Giuliano - May 14, 2016

After WWII and what critic Irving Sandler dubbed The Triumph of American Art the New York School represented the shift of the avant-garde from Paris to New York.

This process was detailed by Serge Guibault in his book "How New York Stole the Idea of Modern Art."

The development of abstraction came to have a number of designations most commonly Abstract Expressionism or Ab-Ex, but also Action Painting and for the critic, Harold Rosenberg, American Type Painting.

The ascendancy of forms of abstraction, not just in the United States but globally, eclipsed the politically charged Social Realism which dominated during the great depression and into the agit-prop era of WWII. There were more benign schools of art in the movements of Regionalism and the American Scene artists.

The avant-garde "triumph" of abstraction was regarded as trumping the provincialism of reactionary forms of American art that preceded the enlightenment. The purity of abstraction, purged of the objective and naturalistic, represented for its critics and exponents a high art that was ultra Apollonian.

As espoused by the leading theorist, Clement Greenberg, figuration in contemporary art was dismissed as anathema. This even extended to the women of de Kooning making him an artist of lesser importance than Jackson Pollock. Notably, Pollock returned to both the bottle and abstracted figuration in his last works.

In studios and panels of the Artists Club, by the 1950s, there was wide spread speculation about a return to the figure. Instead of a second or third generation of abstract expressionism young artists in New York and Provincetown's Sun Gallery conflated the gestural approach and fluid brush stroke into the style of Figurative Expressionism.

With his MoMA exhibition New Images of Man (1959) Peter Selz attempted but generally failed to nail down the emerging figuration. His overview did not include the New Realism which came to dominate the global avant-garde as Pop art. Recent research and exhibitions have widened the source of this art to Great Britain and France.

By the 1960s the orthodoxy of Formalism espoused by Greenberg, Color Field Painting and the sculpture of David Smith and Anthony Caro was shattered. From a purist mind set the money lenders invaded the temple of high art.

The breakthrough resulted in a sonic boom of diverse approaches and experiments including Conceptual Art, Minimalism, Performance Art, Feminism, Photo Realism, Queer Culture, Black Art, Native American Art, Hispanic Art, Earth Works, Sky Art, Pop Art, Op Art, Primary Structures, Outsider Art, Folk Art, Post Painterly Abstraction, Pattern Painting, Psychedelic Art and more.

There was such diversity and proliferation that the umbrella terms of Pluralism and Post Modernism evolved as the notion of one size fits all. The hegemony of post war American art was forever shattered. There were no longer well defined margins and a handful of dominant critics but in fact a cacophony of advocates and innovators.

This also led to new theories and forms of criticism with philosophers edging out traditional art historians in the academy. Much of this was esoteric and European. The artist ceased to be the source of the dialogue. In extreme forms it was adequate to know and analyze the work through reproductions in magazines. Critics made a point of not interacting with artists socially or professionally.

The notion of connoisseurship or experiencing the work through direct and detailed observation was no longer mandated. Criticism focused on thought and theory in which observation initiated the process.

While recently undertaking the monumental task of organizing my vast library, multiple file cabinets of slides and documents, sketch books, notes and negatives I revisited early stages of studio practice and critical thinking.

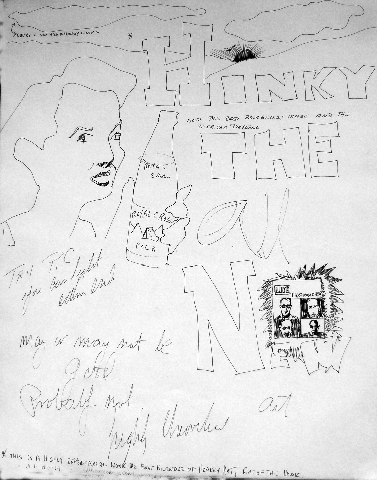

In 1968 I decided to throw my hat in the ring, so to speak, by inventing my own ism or movement of art.

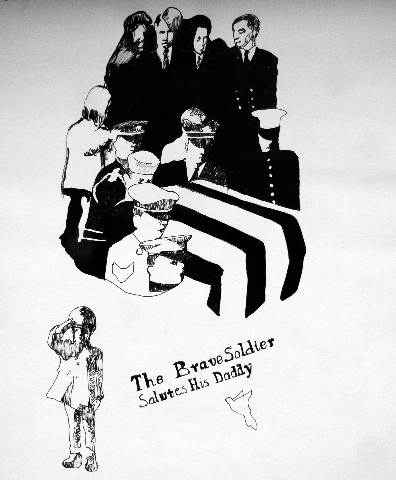

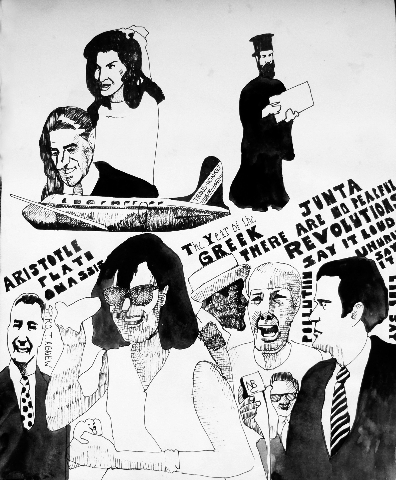

It was a time of war, domestic turmoil, social and political change. There was a new rhetoric generated by the Black Power and anti war movements. I participated in my share of demonstrations and riots. The Summer of Love morphed into anger and rage. You were measured by the depth of commitment to radical change. Were you willing to fight for what you believed in? During that time I was an editor of Boston's version of the underground press Avatar.

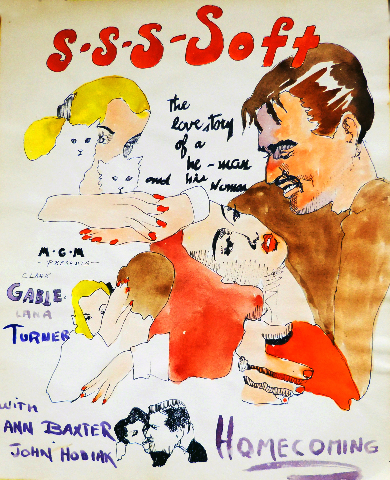

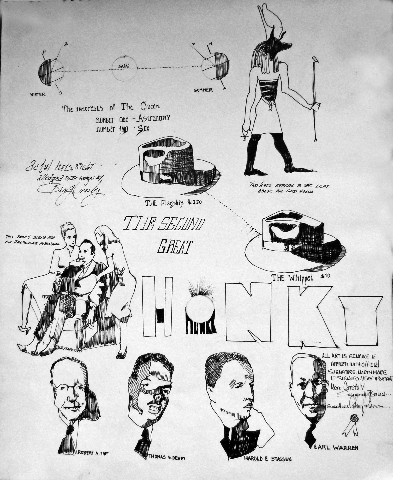

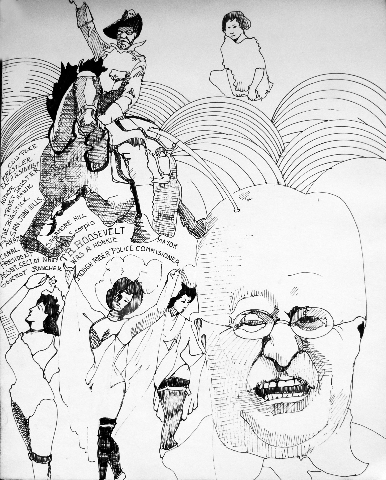

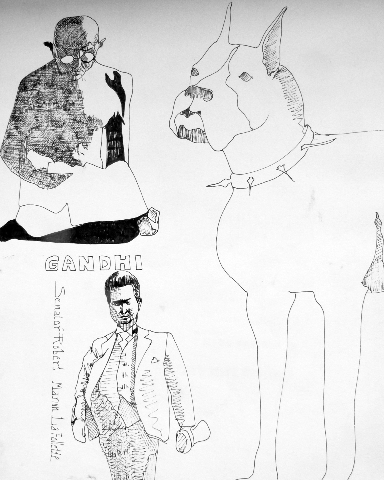

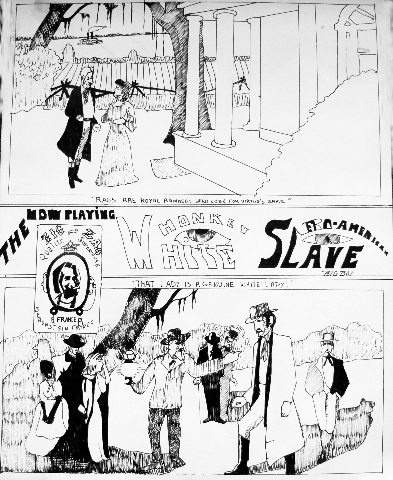

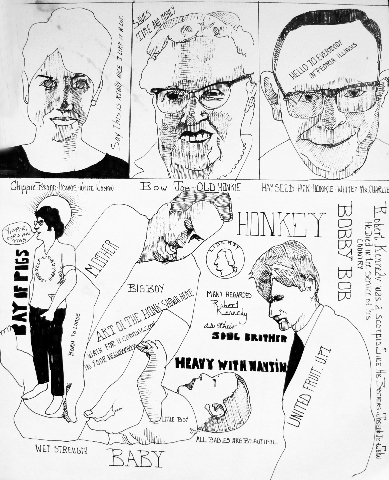

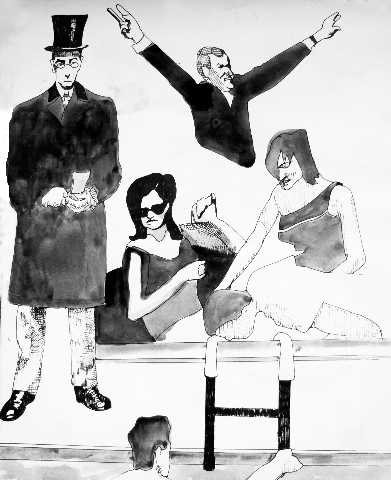

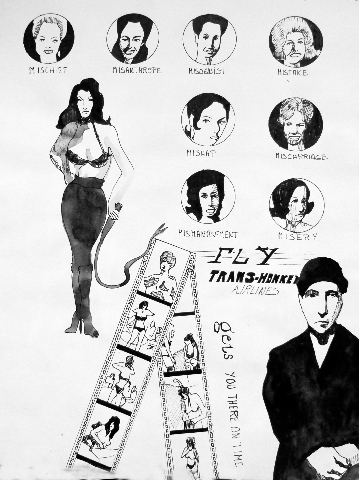

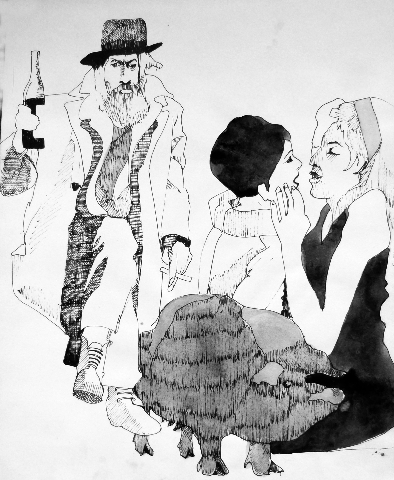

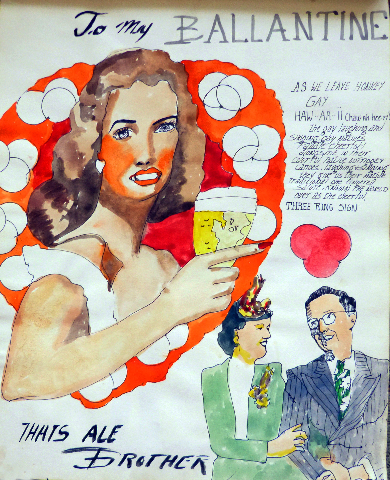

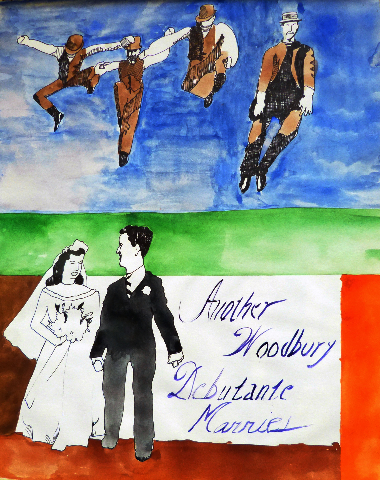

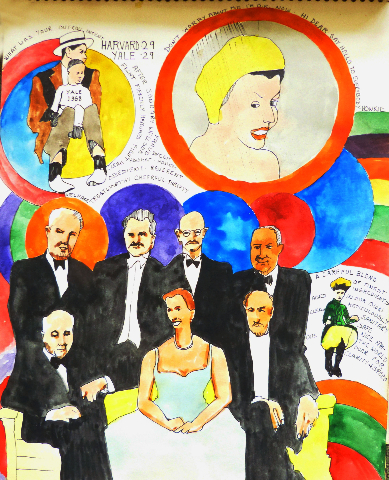

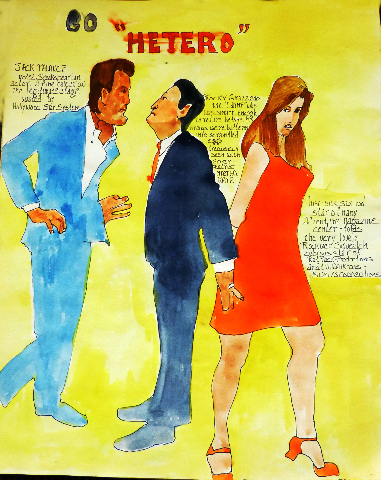

The sketchbook which is revisited here reveals the concept of Honky Art. An art by, for, and about the Honky.

The origin of a then common, derisive term for Caucasians is obscure. It slid into popular culture through film, television and statements of angry young radicals.

Looking back at the images and how they evolved in this series of sketches (not finished works) is both revealing and disturbing. It is a mirror held up to what I was thinking at the time. It is reflective both of my own experimentation as well as how it sources the zeitgeist.

There is a direct connection to Pop art and its imagery but also an effort to give its send up of consumerism and cynical humor a social and political twist.

From the sketch books I was commissioned to create a series of fifty, large scale, watercolor paintings depicting jazz and blues. These were a part of decorating the Royal Sonesta Hotel in New Orleans. This was a project of Joan (Stoneman) Sonnabend the wife of Roger Sonnabend an executive of the hotel chain. When the hotel changed hands the collection was sold and dispersed.

Having delivered the work I continued to create in that manner with a more political focus. With the Boston artist, Arnold Trachtman, we participated in shows of Protest Art at the Community Church Art Gallery, on Boylston Street and a national show in Iowa that included Hairy Who artists from Chicago.

This work was shown at Boston's Warde Nasse Gallery and Dorothea Weeden Gallery.

By the early 1970s my career as an arts journalist developed from Avatar to the weekly Boston After Dark/ Phoenix and then the daily Boston Herald Traveler. When the Herald was sold to Hearst the staff was fired. From then on I was a freelance journalist. Part of the change meant that I had to illustrate stories by taking photographs. That evolved into a transition from painting and drawing to photography as my primary art form.

Looking back at this sketch book from 1968 is essentially a conceptual project. Humorously, it was a one man movement which had little or no impact on the narrative of contemporary art.

For me it is interesting to revisit what I was thinking about as an emerging artist then 28-years-old. It is a time capsule of an era. Now, of course, so much is different yet similar.

During the utter madness of current American politics we are again roiled in a time when it is cogent to revive the humor and irony, the sad and mordant truth of Honky Art.