Berg's Lulu at the Metropolitan Opera

Fabio Luisi Conducts Brilliantly

By: Susan Hall - May 15, 2010

Lulu

Composed by Alban Berg

Libretto by the composer based on the Lulu plays of Frank Wedekind

Conducted by Fabio Luisi

Metropolitan Opera, New York

Lulu Marlis Petersen

The Countess Anne Sophie von Otter

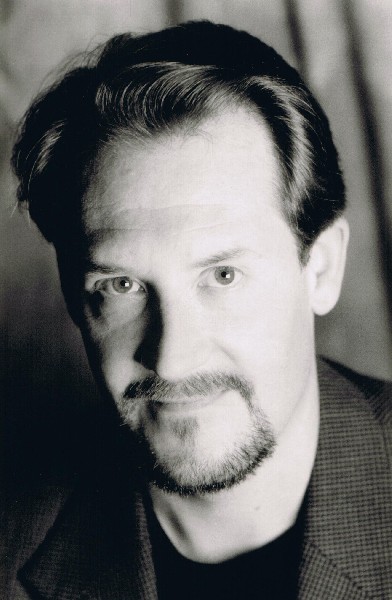

Dr. Schoen and Jack the Ripper James Morris

Alwa Gary Lehman

The Painter, The African Prince Michael Schade

The Animal Tamer, The Acrobat Bradley Garvin

Production John Dexter

Sets & Costumes Joyce Herbert

Lighting Gil Wechsler

Stage Director Gregory Keller

May 12, 2010

Lulu is a perfect way for the Metropolitan Opera to end its season. An opera associated with James Levine was conducted by the Met’s new principal guest conductor Fabio Luisi with great aplomb.

The Met’s wise decision to expand Fabio Luisi’s role in the house was clear this evening. He masterfully draws everything to be heard from the score and keeps seemingly disparate elements in tight control. He has a small, effective gesture at the top of a raised left hand, a twirl that signals the conclusion of a singer’s musical line. It works and also mirrors Lulu’s gesture when she mounts a man, and straddling him, legs akimbo, raises one arm on high, her hand delicately flopping.

A commanding orchestral performance is critical to this opera’s success. With the exception of Alwa, a character who Wedekind made a writer in the underlying play and was rewritten as a composer by Berg, there are no consistently beautiful roles. In this dark, pessimistic piece, the one line that calls out laughter from the audience is Alwa’s comment to Lulu: Your story might make a terrific opera.

Beautifully sung in this performance by Gary Lehman, an American tenor with a richly colored voice, Alwa has some lovely lines which stand out from the brash tones and unexpected, exciting and dramatic leaps in the other voices. The score for the most part, looks on paper the way it sounds: thousands of accidentals binding the music to twelve tone rules, rushes up and down, thickly black. Composed as 12 tone, there are overlays of Mahler, ragtime, oompah band music. It is difficult to unwind the elements of Lulu. Put simply, they work.

Whether or not Lulu is a seductress supreme or a woman preyed upon or both, this opera is a powerful presentation of a particular time and place which sheds light on our own. Women have not yet figured out how to play all their different roles, and men have still not learned how to receive us. As an expert in commercial sex, I know that the work is hard, the only reward money, and often that is not enough. Lulu not only has to work, she has to sing for her supper.

Alwa may be the clue to a good man’s role, but the outcome of his ministrations is not hopeful. The Alwa role bridges the drama unfolding on stage in harsh technicolor and the dramatic and often lush and beautiful sounds rising up from the orchestra.

Another bridge is what’s known in cartoon films as “Mickey Mousing.” The motifs of various characters are clearly heard as they bustle around the stage. The Countess Geschwitz pretends to exit from Lulu’s house in Act II, Scene I. In fact she hides behind the chimney screen. We know she’s there, because her motif is played. Other secret admirers are forced in hiding, but exposed by their musical motifs. Decoding is one of the opera’s pleasures.

Lehmann as Alwa is the character who sticks to Lulu through all her trials and tribulations. One senses, perhaps, real love emanating from him. He is the evening’s most touching character, the most human, although he is not the centerpiece. Berg is said to have identified with him.

Wedekind’s intention for Lulu is clear in the two plays, which Berg edited and adjusted to create this story. A girl of indeterminate origins, she struggles to make a life for herself. It is a harsh, crackling effort.

Marlis Petersen has made this a signature role. She is a consummate actress of super model physical form, not your usual opera soprano. Her visual effect is that of a woman who takes on grotesque ‘feminine’ roles. She was not created a voluptuous woman born to attract.

Wedekind saw “feminine” as a performance role. Lulu actively makes the effort, sometimes egged on by others to satisfy their needs and sometimes assuming a mantle. Petersen is brilliant in the role, which requires singing declamation, notes turned on their edge, and a few Mahlerian lyric moments around her ‘freedom” theme, particularly poignant because she never becomes free.

Is Lulu a breathing, living human or a projection of the characters around her? Critics have looked to the music to see what Berg intended. Berg provides a deliberate harshness and an exterior quality, suggesting that she is only what characters who want to use her want.

Petersen is not a harsh Lulu. She is more wanting and lost. This quality makes us more sympathetic to her. Recalling Teresa Stratas, who performed the premier of the entire opera, she was more cruel and rough in the role. “The director insisted that I be Lulu, not act her,” Stratas says. Perhaps because Stratas had a lot of Lulu in her life. Stratas had a long time affair with conductor Zubin Mehta, but dumped him in the end to preserve herself and not become “Mrs. Conductor.” Lulu is not so lucky.

Lulu is to be sure used by the society around her for its own purposes – embodied in characters each and everyone of whom stand out in this production. An animal trainer, painter, acrobat, theater manager among others.

In the role of the Countess Geschwitz who also loves Lulu, Anne Sophie von Otter is perfect in every detail. This role has some suggestion of a selfless involvement, but is complicated by the Countess’s personal needs. When von Otter is on, she takes possession of the stage. A subtle and moving performance.

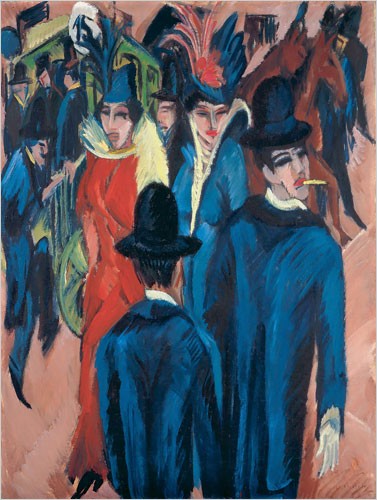

Never once does Lulu dominate one of these characters, although she does occasionally get money from them. The stage scene calls to the mind’s eye German Expressionist Ernst Ludwig Kirchner's Street Scenes series, created between 1913 and 1915, about the same time Wedekind wrote his Lulu plays. Kirchner rebelled against the confining principles of academic painting and the rules of bourgeois society. His acute perspectives, jagged strokes, dense angular forms, and caustic color feel like a visual translation of Berg’s music. Both are filled with vitality, decadence and an underlying mood of danger.

James Morris as Dr. Schoen could well be a street trick in top hat who has just stepped out of a Kirchner painting. How wonderful to hear him sing and know that Morris will perform for a very long time in well-chosen roles. Dr. Schoen is perfect for him, and he is a pleasure to hear and watch. His cameo turn as Jack the Ripper is both seductive and terrifying.

This is an opera, which is so detailed in its linking of the visual, verbal and vocal that it really must be seen. The Metropolitan Opera’s production is stunning.