Open Culture in the Biennale de Montreal

The Bilingual Flavor of This Event

By: Ben Klein - May 16, 2009

The theme of this year's Biennale de Montreal is "Open Culture". A variation on the notion of "Open Society" as well as a nod to today's internet-savvy youth culture, it's a fitting subject for a show in Montreal, one of the world's bilingual cities and also, famously, North America's most European one. There is a current in Montreal of cosmopolitan intellectual curiosity, and diversity, which makes it in certain respects a likelier candidate for such a show than many other, larger cities.

The very word Biennale is a euphemism implying a large-scale, curated art show; which by definition occurs every two years. And while each of the now numerous examples of this phenomenon sprinkled ever more liberally around the globe are inevitably linked to a city (as signally for example Venice) and thus, to highly particular cultural characteristics, the core idea of "The Biennale" in itself is that contemporary art is an emanation of internationalist culture; like big science, or the film industry, the basis of the thing in question cannot be confined to a "school" as was the case with art in previous times.

Whereas, in the 17th century, strong use of the color black, in European painting, implied the Spanish school, there are now no obvious stylistic markers in contemporary art which identify the nationality of any given artist. Coming upon their work in the rooms of one or another Biennale, anywhere in the world, from Prague to Sao Paulo, we confront the power of art to link all of humanity in intellectual rhythm; and hear the hum of a sophisticated conversation that would seem not to require any definite verbal or linguistic accommodation, accord, or coincidence. There are still schools of art , but they transcend national borders, and have more to do with subject and stance, rather even than media, language, or ideology. This is reflected in both the media and the message of the 2009 Biennale de Montreal, which was presented by Director General, Claude Gosselin, with all of this as a basic principle.

If Biennales are transnational crystallizations of art world tendencies, those developments are being generated somewhere else, equally without restrictions on place. Art schoosl, art galleries, and art studios themselves are much the same all over the world.

In her excellent recent book "Seven Days in the Art World", Sarah Thornton devotes a chapter to "The Crit", meaning the practice in art school (frequently kept up by artists for life) of having an open discussion in which all bets are off and one can say anything about the artwork in question without censorship or fear. The fundamental assumption involved is reciprocal altruism, offered in the form of a no-punches pulled truth session and powwow.

The Crit is parallel to the scientific practice of peer review; in fact it's an art world version of exactly that. Peer review is a notion central to scientific inquiry, because in the hard sciences only the practical merit of an idea can establish it as important in the face of conflicting ones; therefore, meritocracy must be achieved, and for this, only openness and freedom can offer even the slightest hope of a guarantee that we might be able to see which door we ought to open, standing in a hall in which there are millions. Hard as this all is, and similar in so many creative respects to art, science can, in general, know with relative assuredness when the proverbial dove sleeps in the sand. Art doesn't and can't, its nature compels it to a slightly more complicated destiny. The coping mechanism is the art piece per se.

An artist makes a work; the work deals with a subject. Art is potentially infinite, and if we accept the post-structuralist idea of the free play of the signifier, then every example of it may even be so, in some sense; but pragmatically, the art piece metaphorizes an idea of some kind, including ones which are already metaphors, by presenting them in physical form for our consideration.

The artists in the Montreal Biennale have been pulled together into a matrix whose shape reminds us directly of this scientifically inspired procedure. One very good example for instance, is the wall-based, mechanical writing machine piece "Read/Write" installed on the second floor of downtown Montreal's historic Bourget Building, the site of the Biennale this year by Mathieu Bouchard and Alexandre Castonguay. It works interactively; the audience programs it with phrases of their choosing, and it writes their messages on the wall. Visually the result is quite surprisingly spectacular; ghostly, not a little unsettling but somehow intimate, clearly a statement of intellectual egalitarianism.

The piece seems to reference virtually every text-based artwork ever made, as well as both the grid structure and time-compression of analytical cubism; and Cy Twombly and Jasper Johns' writerly, Neo-Dada critique of indexicality.

The authorial, autograph mark is back under attack here, but not in a way which refers to any politics, at least not directly. Individuality and system both persist, the work seems to say, which is alright; no one is harmed by the mere existence of either. It is the interaction of the two which works out for better or worse in the real world, a fact brought clearly to mind by a phrase near the center of the wall that stands out as a known signifier, and presumably needs no introduction: "I'll be back". The Terminator films themselves seemed to make a similar case about the cross-purposes of human beings and their creations, a notion plausibly as true about art as it is of technology, made poignant by "Read/Write".

Another good example of openness as demonstrated by artists, in the best sense, is the collaborative installation called "Soundscapes", organized by Claudio Marzano and Scott Clyke, and also on the second floor (of three). In it, a musical composition inspired by Rick Leong's beautiful painting "Dancing Serpent in Dawn's Quiet" plays, in the company of two other of Leong's large-scale, atmospheric dreamscape paintings

Leong's motivational painting is absent but seen in a video projection. This allows the viewer to contemplate its facture and lovely finish in the paintings that are on site. This is projected alongside a rare glimpse in the gallery context of our more mundane and regular seeing of paintings, that is as mediated by cameras, both still and moving. These several elements combine to create quite a remarkable atmosphere, in which a child-like aura surrounds us, without cloying or dictating terms. It is uccessful because open.

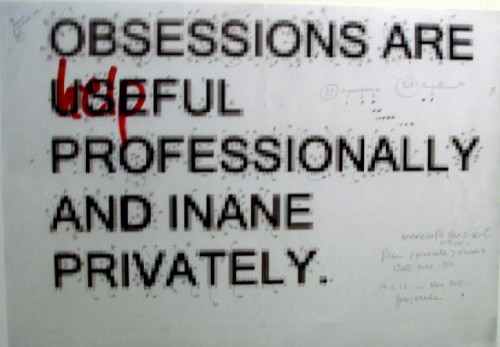

"Obsessions are helpful professionally and inane privately" a quotation of Stefan Sagmeister, the well-known Pop graphic designer is the center of a group of work, by a crew of artists, at the back of the building on the first floor. Around this canny and unnerving utterance is built a whole section of the Biennale, including heterogeneous pieces by for example Marie Leviel, Valerie Bouvrette, and Augustina Woodgate, all of which along with the others incorporate Sagmeister's words as text, and which appear to synthesize, alone and in ensemble, various thoughtful emotional timbres to the great composer's tune. Thinking about thinking about art about art is fun as it turns out.

In his book "The Open Society and its Enemies", the philosopher Karl Popper goes into detail about the dangers and vulnerabilities inherent in, what is for human beings, the truly radical notion of a culture or society which has de-centralized its power structure and arrived at a social stability in which no one is unchangeably more powerful than anyone else; constant vigilance is required for it to be practicable. In art, we now have something like the equality Popper proposed, in that anything can be made into it; accepted and critically validated, in terms of media, materiality or style. This fact the Biennale de Montreal illustrates admirably.

A wistful criticism, once you've toured the show, is that there isn't more. The Great Recession 2.0, ugly enemy of art that it is, can be nonetheless stared down, and denied victory by this show, by an art that celebrates and raises up both community and individuality. Philosophically speaking, existentialism and structuralism have been made into a sensual dessert that tastes quite delicious.