Jaime Thibault, An Acadian Artist

Fine Art of Functional Objects

By: David Wilson - May 17, 2011

National authorities such as the Canadian Museum of Civilization claim that Folk Art is near extinction in Canada;“Around 1990, handmade outdoor folk art ceased to be produced in any quantity and, at the same time, home-owners stopped displaying it. In the words of one canny gallery owner, who suddenly had no more folk art to sell, ‘No one is naïve any more.’"

And even though the borderline between “Folk Art” and “Fine Art” often has very muddy demarcations, I have no doubt that Jamie Thibault is both a folk artist and a fine artist of noteworthy stature. A single visit to his workshop or dropping in to his website, www.jamiescarvings.com gives ample evidence.

Born and raised in the village of Grosse Coques, that’s French for “large clams,” Jaime, even as a pre-teen was drawn to the carvings of another local, but aging, Acadian Artist, Clement Belliveau and set about attempting such work on his own.

He began with efforts to commemorate that most prized object, the humble yet ubiquitous skateboard. It provided an object that could be fashioned in a wide variety of shapes and embellished with infinite motifs. Skateboard miniatures allowed him to develop his technique and to assemble the tools of his trade, chisels, gouges, rasps, saws and a few he fashioned himself. Later he acquired power tools, sanders and polishers, used primarily for surface finishing.

Now, approaching 27 years in practicing his self-taught craft, married to writer/photographer, Angel Flanagan, and father of two young boys, Jamie continues to expand his technique and vision, turning his hand to crafting an ever widening catalogue of objects.

I first became aware of Jamie as an artist several years ago when Marc Graff, publisher in Nova Scotia of the Clare Shopper, showed me one of Jamie’s pieces. It depicted a scene of fly fishing at a camp, approximately 6 inches by 12 inches, so detailed and so three dimensional, it was hard for me to believe that it had been crafted by anyone who had not been academically trained. Subsequently I found that Jamie had seldom been more than a few miles from his hometown and was as unlikely a person to go off to school as any I have ever met.

True to the folk artist tradition, many of Jamie’s creations are functional objects. They include skis, stools, gun-stocks, canes, walking-sticks and of late, violins. Much of his work created for its aesthetic value alone attains the stature of fine art integrating technique with a brilliant sense of shape, composition and texture.

His recent work includes representations of the natural world oddly congruous aside those cultural icons of his youth and the fantasy genre, wizards, warriors and fantastic creatures, dragons included.

During my brief visit to his studio I was taken with one item after another, though, so much of his work is commissioned, done to order, only those works in progress and treasures he is reluctant to part with are at hand.

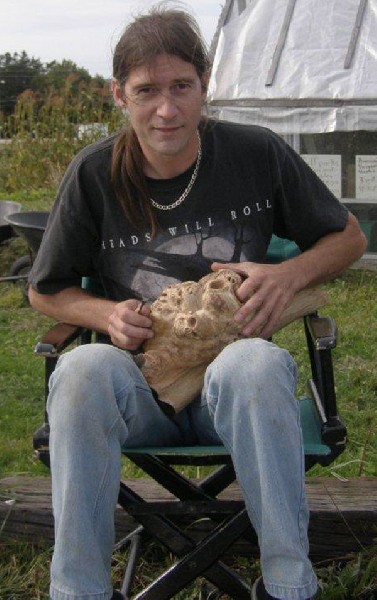

At one end of the space, a carved sign denoting the studio is in process, several wood burls, yet to be touched, take up another spot. From a shelf, Jamie takes down and places in my hands an elaborately carved object that at first glance seems to be an odd shaped bundle of skulls. When held at arms length it turns out to be the head of a beast, most likely a dragon. This piece contains 50 skulls and took over 270 hours to create.

As I carefully set it down, Jaime passes me another gleaming object, so light in comparison to the one I have just set down that I fear for a moment I do not have it firmly in hand. It is his latest completed violin and the second of three that he has been crafting.

The Acadian Star embellishes the neck. The back displays a texture and finish that is almost three-dimensional and gives a sense of looking into depths. When I ask him how he learned to create such a marvel, he tells me that it is a craft he has recently learned from his cousin who has been constructing fiddles for many years.

When I ask if he has many orders for instruments he tells me that it will take a few years for the quality, the durability and the credibility of his work to be proven and he does not expect that to happen right away. He is content until the reliability of his work is established to make his impact in that market with hand carved pegs, chin rests & tail pieces for which he has orders.

Among his most popular items are the gear-shifter knobs he makes for his car-customizing friends and their acquaintances. For awhile he created a number of ornate pieces from the Tagua nut of South America, but stopped, the result of a worsening allergic reaction to the Tagua dust.

In a few short years, Jaime has gone from creating the odd custom piece for a friend or acquaintance to a regular presence at the local craft shows and farmers markets where he lends his artistry to jewelry as well, using natural beach stones, beach glass, shells and silver. These appearances along with his website and Facebook page are generating an increasing awareness of his work and an audience always anxious to see his next creation.

His most recent work, and one of his most stunning, Vanishing Cream, is the carving of an image which first saw light as the charcoal drawing of Tattoo artist, Jaimie MacKay. With permission granted, Jaimie Thibault traced elements of the original art to the surface of a slab of spalted maple and began to carve. A sequence of photos on his website shows the elaborate process from beginning to end.

It might be time for someone to tell the Canadian Museum of Civilization that Folk Art is not as near extinction in Canada as they may have feared.

(The author wishes to express his gratitude to Angel Flanagan for her assistance, fact checking and photographic contributions)