Met Opera Orchestra at Carnegie Hall

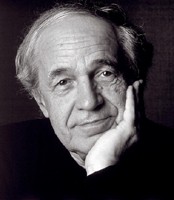

Pierre Boulez Debut at 85

By: Susan Hall - May 18, 2010

Pierre Boulez Conductor

The Metropolitan Opera Orchestra

James Levine, Music Director

Deborah Polaski, Soprano

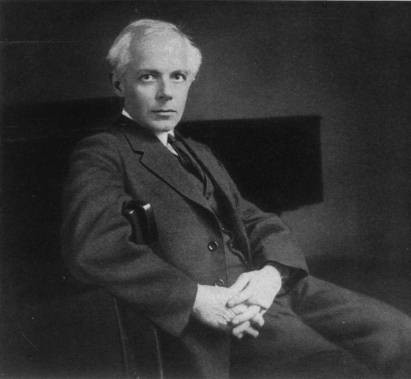

Bela Bartok, The Wooden Prince, Opus 13

Arnold Schoenberg, Erwartung, Opus 17

Carnegie Hall

May 16, 2010

Pierre Boulez is expert in Bartok and Schoenberg, whose difficult pieces were performed brilliantly under his baton on Sunday. The Metropolitan Orchestra passed a challenging test with flying colors.

One orchestra member noted sadly that this was the first Carnegie concert without James Levine, but Boulez, remarkably making his Met orchestra debut at 85, was splendid in two seminal compositions of the modern repertoire.

The Wooden Prince, an intriguing score created for the ballet by Bela Bartok, was performed without illustration. The dynamics of the piece are extraordinary, ranging from almost inaudible pianissimos to the loud crashings of percussions. Still shrilling of high woodwinds, a muted trumpet, and tam-tam excite, but cry out for visual translation.

Both pieces in this program address concerns about the body, its materiality and whether or not it is central to meaning. In the Bartok, a puppet grafted from the prince’s sword, staff, regalia and hair becomes the princess’s love object.

Composed after a disappointing premier of his opera Bluebeard’s Castle, the Royal Hungarian Opera House had defied public opinion and asked for a composition based on a Béla Balázs text.

Bartok was discouraged and “did not feel like writing it.” Writing for his “desk only” he finally delivered The Wooden Prince in May of 1917, but trashed the commissioning Opera House. “What is the Royal Hungarian Opera House anyway? An Augean stable, a dumping ground for every kind of rubbish, the heart of all disorder, the pinnacle of confusion…people are already sharpening their claws against me.”

The Wooden Prince was a huge success. Palindromic in structure, it opens with a lulling C major, evoking a generalized impression of nature, peaking when the Prince tries to entrance the Princess, and returning again to nature at the end. Lush nature portions sound invitingly loose and carefree. The center is more tightly structured. Our attention is riveted by fragmentation, rhythmic distortions, “a shattered frame.”

Bartok famously researched folk tunes, particularly those of Hungary. Inspired by Franz Liszt who wrote on “Gypsies and their Musical Hungary” as a preface to his Hungarian Rhapsodies, Bartok roamed the countryside recording native song. Often the harmonies of these songs crept into the harmonies of his work. Like other composers, Bartok wanted to create accessible music, using new forms but providing familiar signposts. In The Wooden Prince, particularly the central section, Bartok succeeds.

Borrowing also from carnivals, masquerades and French cabaret, like Stravinsky’s Petruska, a puppet dances. The question: Is the body alive or made of wood? Is it the center of meaning?

Schoenberg also addresses the centrality of the living body in Erwartung –expectation. While the Bartok alternated between dream and nightmare, Erwartung is pure nightmare. A woman searches for her unnamed lover at night in a dark forest. Is he with another woman? Is he waiting for her? Has something happened?

Boulez, of course, is a composer himself. At 27, and identifying himself as a post-Webernist, Boulez wrote an article entitled “Schoenberg is DEAD.”(caps his). But as he conducted, it was clear at 85 he has mellowed. More recently he wrote that the second period of Schoenberg’s work, his expressionism, is ‘visionary' and that Schoenberg “played a unique role as a composer.”

Erwartung falls into the second period. Schoenberg wrote: “…one must listen to it [my music], forget the theories, …the dissonances, etc. and I would add, the author.” Boulez thought the author a little messianic, so given permission to forget him as a man, he does.

Schoenberg is only beginning to be appreciated as a man in full. He taught film composers in Los Angeles. Asked by one how he should compose for a scene showing airplanes, Schoenberg recommended making them sound like big bees, only louder. His sense of humor is underappreciated.

A young John Cage, Leon Kirchner and Oscar Levant were all taught by Schoenberg. Levant attended a performance of Schoenberg quartets with George and Ira Gershwin and remarked that it was one of the high points of his musical life.

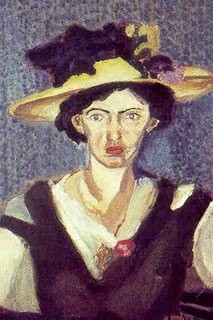

The moods of the Erwartung monodrama each have their own color. As a painter, Schoenberg was preoccupied with the impact of color and color combinations. Alma Mahler, visiting his home, noted that each room had its own color. The switches from mood to mood in Erwartung are abrupt and difficult to execute, but in this performance, they were exquisitely colored by the orchestra and by Deborah Polaski, the noted dramatic soprano.

As the tall, gracious Polaski took the stage to sing, we are reminded that short men have to look up. She is a foot taller than Boulez, but he has obviously learned to handle height or the absence thereof. Schoenberg too was short, and quoted Balzac: “He was of medium height as is the case with almost all men who tower above the rest.” In Boulez’ hands, Erwartung and Polaski towered.

Since the Second World War, Polaski has sung more Brunhildes at Bayreuth than any other dramatic soprano. She is magnificent in this Erwartung role, new to her repertoire. Another composer wrote that Erwartung “acted out with terrible personal intensity the dilemma of the world gone haywire.” Polaski calls forth conflict, doubt and yearning, all with great beauty.

A monodrama, Erwartung has no themes, only moods, based mostly in fright and pain. Written by medical student Marie Pappenheim, whose cousin was one of Freud’s hysterical patients, the unnamed singer is above all scared. When Polaski discovers the body and soars from pianissimo to fortissimo, from a middle G sharp up to a high B holding it for three measures, the word she sings is Hilfe – help.

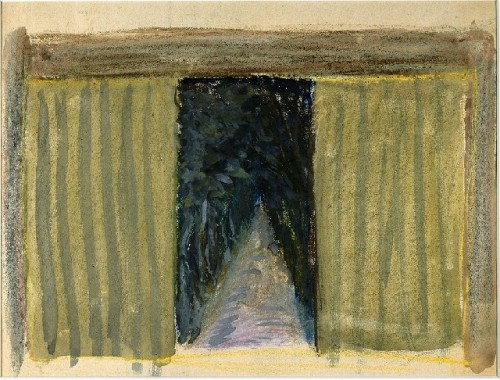

The painter Kandinsky and Schoenberg were friends. When they met, Kandinsky was changing, his colors taking on a life of their own as representational shapes becoming images to be interpreted by the viewer. This could be said also of Schoenberg’s music.

Schoenberg wrote the piece in 17 days, as if in a dream. He wrote clear directions: The singer must fear the forest in which she is lost. This must be a nightmare and transformative moments must take place without a break. What a tall order! Looking later at the drawings Schoenberg made for the production (we have included them here), there is no question that Polaski and Boulez realized Schoenberg’s wishes.

Schoenberg cared about being heard. In an essay called “My Public” he told the story of a hotel elevator operator who asked if he was the composer of Pierrot Lumiere (written at about the same time as Erwartung). The elevator operator still had the sound of that music in his ears. He was told that the musicians did not know what to make of the piece, but he got it. Schoenberg beamed telling this story. Everyone certainly understood both Bartok and Schoenberg in these performances.

Alban Berg wrote of Schoenberg, “…whoever hears these melodies just once will forget all I have said about them, and will simply sense their soul.”

Above all, this was an afternoon of beautifully rendered soul music.