Freedom Riders: An American Experience

A Journey for Justice That Became A Trip To Hell

By: George Abbott White - May 18, 2011

Firebombed buses and escaping passengers brutally assaulted sounds more like the Middle East and Pakistan than mid-20th Century America. But a short fifty years ago such scenes and even more violent encounters were commonplace in the Deep South as the Civil Rights movement moved into the Sixties, gaining shape and mass.

What the Freedom Riders of 1961 did and what was done to them for daring to expose state and local “Jim Crow” laws and norms to the United States and the world was heroism of the highest order. Yet for the 400 black and white (chiefly) young women and men who sat together on Greyhound and Trailways buses from May to November, say Washington, DC to New Orleans or New Orleans to Jackson, Mississippi, it was far simpler and far more complex.

Exposing a region’s non-compliance with previous Supreme Court decisions provoked inevitable and terrifying KKK/mob attacks. The rides shattered and enhanced individual lives, jolted then refocused the Kennedy administration’s attention, from an international Cold War to a hot domestic race war.

Younger brother Attorney General Robert Kennedy found what had been called an “American dilemma” could neither be managed nor contained, and the FBI was a reflexively untrustworthy partner. Both Kennedys discovered the rides were neither accidental in origin nor random in purpose. Their proposed “solution,” meant in part to divide and dissipate the “unreasonble” youth of the Congress of Racial Equality (CORE) and the Student Non-Violent Coordinating Committee (SNCC). And their older supporters, ironically only raised the struggle and stakes to a higher level.

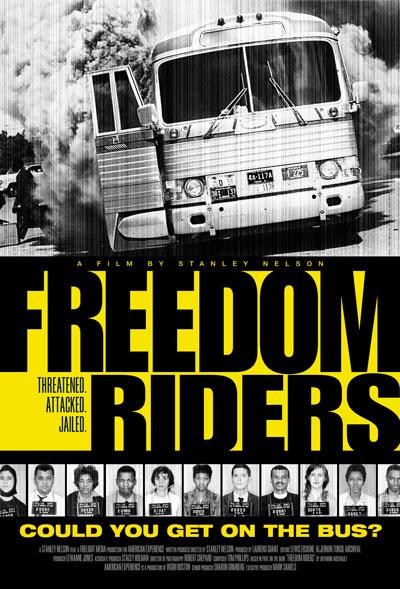

All this is dramatized with great skill in the recent PBS American Experience, “The Freedom Riders.” Still more is suggested by a substantive and evocative web site that provides background, personalities, time lines, mug shots and maps.

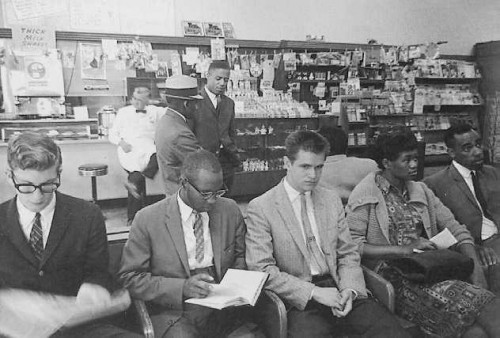

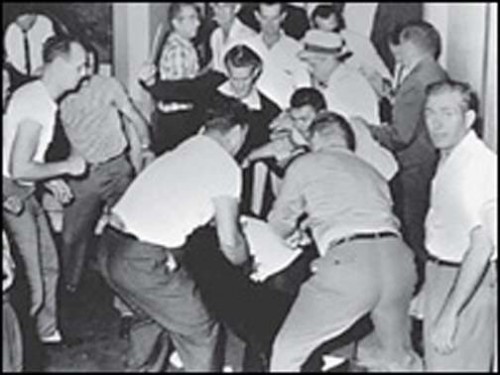

With then-contemporary music, participants’ interviews, powerful black and white stills and even more powerful network and hand-held “motion picture” clips, the documentary keeps to a roughly chronological account of the year’s overall journey. It is punctuated by shots of psychologically insulting waiting room signs, “Colored Only” and “White Only” as well as physically insulting attacks of riders getting on or off at Memphis or Montgomery.

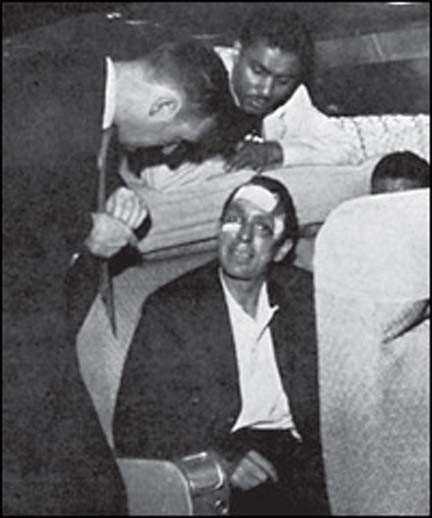

Shockingly (or perhaps not so shockingly) they are set upon by angry white men with baseball bats, chains, cold-cock fists, bloodied and battered unconscious. A viewer’s experience is ring side at a slug fest, vivid and exciting but shameful and humiliating, too. How could the state and local police in attendance allow such lawlessness? How could these “wholesome” youngsters (dressed in “Sunday best”) not strike back, even defend themselves?

The message penetrated deeply: this handful of students (black and white, northern and southern) and clergy (ministers, pastors, priests and rabbis) were “outside agitators” to some and the “new Abolitionists” to others. The buses, we see, were literally the Riders’ vehicle for enabling America to see that laws on the books were empty and inert without a supporting social or even judicial context.

Gandhi’s non-violence was the Riders’ method for exposing and confronting, directly, that mailed fist inside the soft glove. This was an uncompromising, all encompassing social construct of another sort, the “Southern way.” This way of life would be defended by any means necessary, legal or illegal, by custom or noose. The hell with laws, Jim Crow reigned supreme.

For those who were around then the faces and the issues, pervasive racism and institutional resistance and government indifference, have a profound familiarity. Younger Americans who got their history of the Sixties from Hollywood or Oldies or hearsay, will learn of deeds not behavior, something quite different than sex, drugs and rock ‘n roll later in the decade.

The New Frontier this PBS film suggests was not so new, liberal or quick to support youthful idealism. With Jack and Bobby Kennedy, we see reaction rather than action, moral hairsplitting not “costly grace,” official doubletalk (even between officials), and national gridlock. The utter and clear irresponsibility of state leadership and inability to see beyond a state’s borders, under the guise of “state’s rights,” especially, has disturbing dumbed down relevance.

If JFK, RFK and the FBI get their due, one group does not. The clergy were part of the Civil Rights movement from the beginning, but in “The Freedom Riders” one rabbi says a few words for the camera and the rest is silence. The graphic violent images spoke to a nation.

Albert Camus, oft-quoted by the SNCC students, insisted in a much read essay that the Church speak out, “loudly and clearly.” The clergy were reading Camus. They were also reading Dietrich Bonhoeffer, the young German theologian who had urged his fellow Christians to “stick a spoke” in the wheel of Nazi injustice. His consistent witness against the Nazis had him martyred at age 39, a few weeks before the war’s end.

While the official church in America, and embarrassingly the white Southern ones, generally did not act or even speak out, some clergy did, at least enough to be noticed from Greensboro lunch counters to the infamous Selma bridge.

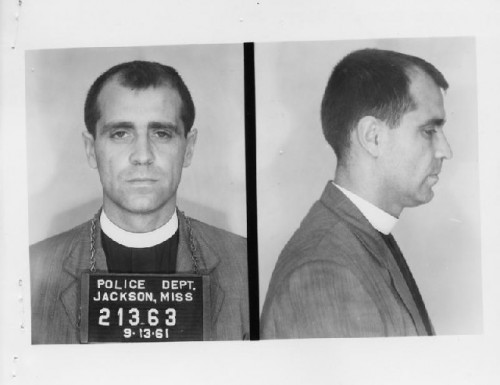

Indeed, the Episcopal priest who married my wife and I almost forty years ago, Rev Myron B (“Mike”) Bloy, climbed aboard a New Orleans Trailways bound for Jackson in 1961 with no less than 14 other Episcopal clergy. Rev Vernon P Woodward from Cincinnati at 27 was the youngest, Rev Quinland Reeves Gordon from Washington at 44 was the oldest. Woodward was white, Gordon black. However, it’s not clear they took a greater or lesser risk leaving September 13th , so late in the cycle. Mike Bloy was 35, living in Newton with three young children.

I first met Mike at the University of Michigan in 1964, and then while visiting Harvard and other Boston area graduate schools, stayed with him and his kids around Thanksgiving 1965. While attending a Washington Cathedral conference in 1985, he died in his sleep with a book in his hands.

A decade after the Freedom Rides, Bloy knew I had been involved in Civil Rights while at Michigan but never mentioned what he had done. “It was not something my father volunteered,” said Bloy’s youngest son Peter, still a Boston resident. “My siblings and I knew he had been hauled off the bus in Jackson and jailed in Parchman Penitentiary but whatever we learned about that pit, was not given with a smile.”

Rev Jack Smith, minister to Boston University students for decades and a colleague of Bloy’s acknowledged many were “anxious and fearful” but rode the buses “because that was what their calling called them, in that time and place, to do.” They did not “sit in judgment of others who did not,” said Smith.

Georgia Congressman John Lewis describes in the film the terrible beatings of others but says nothing about his own near-death experiences. His face was rearranged. “They knew what they were getting into,” said Tony Stoneburner, a professor and Methodist minister who was Bloy’s best friend since the 1950s. “They knew by that point in time people were waiting for them.”

Asked why Bloy did it, Stoneburner saw a number of reasons. “It was a matter of justice,” he said. “If the essence of the Christian life for a man like Mike was to seek justice, that was a reason. He did not construct an intricate argument. He did not seek that kind of risk, but neither did he dodge it in carrying out what he believed was a necessary confrontation.”

Was there anything special about doing it as a group? “Well, the Episcopal Church at that time had few Black members,” said Stoneburner. “You could say Mike and the others were certainly doing something for their church, but not to enlarge membership so much as to say, ‘Our participation permits us to be with you. We demonstrate that we are sympathetic to your situation.’

“This was a communal action, for a large community” said Stoneburner. “Mike was inclusive, he was always trying to build community and always trying to seek justice. The edge of justice has to be kept sharp. Mike and the others’ witness was their way to do it.”

The Freedom Riders teach us that great change can come from a few small brave steps taken by extremely courageous ordinary people who did extraordinary things.