Mark Morris Dancers Acis and Galatea

Nymphs and Shepherds Frolic at Boston's Shubert Theatre

By: David Bonetti - May 18, 2014

Acis and Galatea

Mark Morris Dance Group

With the Handel and Haydn Society Orchestra and Chorus

Presented by Celebrity Series of Boston

Shubert Theatre

May 15, 16, 17, 18, 2014

Premiered at University of California, Berkeley on April 25.

Future performances scheduled for Kansas City, the University of Illinois at Urbana Champaign and New York City

Music by George Frideric Handel (1718), arranged by Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart (1788)

Libretto by John Gay, with Alexander Pope and John Hughes

Mark Morris, director and choreographer

Nicholas McGegan, conductor

Adrianne Lobel, scenic design

Isaac Mizrahi, costume design

Michael Chybowksi, lighting design

Vocal cast:

Sherezade Panthaki, soprano – Galatea

Thomas Cooley, tenor – Acis

Zach Finkelstein, tenor – Damon

Douglas Williams, bass-baritone – Polyphemus

Dancers: Chelsea Lynn Acree, Sam Black, Rita Donahue, Domingo Estrada, Jr., Benjamin Freedman, Lesley Garrison, Lauren Grant, Brian Lawson, Aaron Loux, Laurel Lynch, Stacy Martorana, Dallas McMurray, Maile Okamura, Brandon Randolph, Billy Smith, Noah Vinson, Jenn Weddel, Michelle Yard

Photos courtesy of Mark Morris Dance Group

I don’t believe in God or the afterlife, but if I am wrong and I am judged to have been a good man, please God let my heavenly reward resemble the opening scene of Mark Morris’s often intoxicating version of Handel’s beguiling chamber opera “Acis and Galatea.” As the off-stage chorus sings the rustic-sublime, “O the pleasure of the plains!/ Happy nymphs and happy swains,/ Harmless, merry, free and gay,/ Dance and sport the hours away,” which makes me mist up every time I hear it, Morris fills the stage with his company of nymphs and shepherds dancing the most joyful set of couplings and uncouplings I’ve seen since his great “L’Allegro, il Penseroso ed il Moderato,” also set to Handel, some 20 years ago.

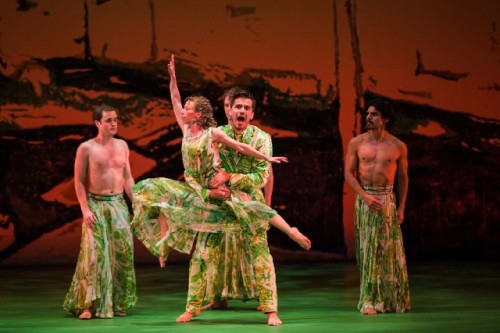

Morris’s nymphs and shepherds are all young, slim and lithe – they’re dancers, after all. Dressed by Isaac Mizrahi in loose, gauzy pajama-like costumes with abstract green, white and faded red patterns that look like the sun shining through dense foliage, the men shirtless, they embody a natural innocence that embraces a happy sexuality. They suggest a model for our own behavior, so often degraded by fear, hate, greed, jealousy, etc. - the seven deadly sins multiplied these days by cyber-digits. Morris and his company of happy rustics – like Robin Hood and his Merry Men (and Women) - remind us of our better selves. All for one and one for all. Walking, running, skipping, jumping, falling and rolling on the floor, occasionally lifting one above the others, they propose a new, but ancient, model of behavior, in which all are equal, but all are individual. You can see it in the variety of the male dancers’ facial and chest hair.

There is always a political dimension to Morris’s apparent simple pleasures. His is essentially a hippie aesthetic nurtured in the free-to-be-you-and-me world of Pacific Northwest egalitarianism. And I don’t think the emphasis the chorus puts on the phrase “free and gay,” at least for these performances, was unintentional. They were John Gay’s words, which had different meanings when he wrote them than they do now, but how extra-meaningful they were being sung in the Shubert Theatre on the tenth anniversary of the first marriage licenses issued, thanks to a Massachusetts court decision, to same-sex couples, which has gone on to change America’s attitudes toward love and difference. Even the views of a socially conservative president “evolved.”

If only it had all been so rapturous. But heaven is a hard concept to spin out into a full evening of entertainment, and at best we get to glimpse it for a few moments before reality brings us crashing down to earth. As Auden said about Dante’s “Paradiso,” “Heaven is an acquired taste.” We can savor it for the moment, but do we really want to live it?

In other words, it got a little boring, although the dance and the music were always of stellar quality. How long can we watch handsome young men and winsome women circle dance and couple and uncouple? With Morris probably more than we otherwise would, but, still, there is a limit.

Relief from the endless happiness – another chorus, “Happy, happy, happy we!” - thankfully came in the second act when evil enters the land of eternal sunshine. We heard it foreshadowed in the overture, when dark tones entered toward the end of a snappy little sinfonia. The evil appears in the person of the one-eyed Cyclops Polyphemus who lusts for the neried Galatea who loves the shepherd Acis, whom he then kills. The concept of death interrupting an idyll derives from Ovid, who was also the source of the story adapted by Handel. French Baroque painter Nicolas Poussin gave us the best image: a quartet of shepherds and nymphs discovering a tomb in their Eden with the inscription “Et in Arcadia Ego” (I – death - am also in Arcadia) shocking them into awareness of the temporal limits of their joy and their existence.

We must take a look at the plot, because this is after all an opera as well as a dance, and it has a story to tell. (During intermission, I walked out onto the sidewalk for a moment where I overheard a woman on her cell phone say, “I’m at the Boston Ballet, which isn’t really ballet, but there’s also an opera going on and it’s kind of confusing - but I like it.”)

The story goes that Acis, a mortal, is in love with the sea goddess Galatea, who loves him in turn. The Cyclops Polyphemus lusts for Galatea, and when she spurns him, kills Acis by hurling a rock at him. Galatea, grieving for her loss, uses her powers as a goddess to turn her dead lover into a river, which still flows in Sicily, where the story takes place.

This is a chamber opera that grew out of a masque given at the house of a noble, not in a public theater, so it is relatively short and uncomplicated by the standards of Baroque opera. On commission Mozart enlarged its orchestration, but he seems to have jettisoned one of the five characters from the original, leaving just four. Because it is being done in mid-size theaters, not a count’s drawing room, Morris chose to set his “Acis and Galatea” to the Mozart version, which has more strings and a bassoon, clarinet and horns. Nicolas McGeghan conducted the Handel and Haydn Society Orchestra with verve – the period orchestra tends to play Mozart like Handel anyway – but I missed the crispness of Handel’s original.

Morris has adapted some dozen operas to dance. In some, like Purcell’s “Dido and Aeneas,” arguably his greatest achievement in the form, the vocalists sing off stage. In Rameau’s “Platée,” another triumph, singers and dancers both occupy the stage. He’s followed that model in “Acis and Galatea,” but less successfully. In “Platée,” although the singers sang and the dancers danced, they seemed to occupy one unified theatrical world. In his new work, that unity seems to be more elusive. Whenever the singers appear they seem to interrupt the action - or get lost in it. Part of the problem is visual. Neither Thomas Cooley’s Acis nor Sherezade Panthaki’s Galatea is physically right for the production. Cooley is tall and portly; Panthaki is short and squat. Morris’s acceptance and even celebration of difference among his dancers is admirable – and radical. But with these singers it resulted in discordant stage images.

The arrival of Polyphemus in the second act made all the difference. It’s not unusual that the bad guys get all the best lines or, in opera, arias, e.g., Don Giovanni in Mozart’s masterpiece, named for the villain who is damned to hell, not the wimp, Don Ottavio, who ineffectually seeks revenge for his wronged lover.

Morris’s most successful integration of singer and dancers was with Polyphemus, which has a lot to do with the skills of Douglas Williams who sang and acted the role with panache. But the one-eyed monster also gave Morris the greatest opportunity to invent a new, disturbing iconography for him. Polyphemus is usually presented in the decorous Baroque manner as a standard, cut-to-order villain. Morris created a psychologically more complex and disturbed creature like Shakespeare’s Caliban, who is unsocialized but longs for human society. I couldn’t help but think of those profoundly hurt boys who shoot up their high schools. Not only does he lust for Galatea, he lusts for everyone. During his great aria, “O ruddier than the cherry,” he gropes the terrified inhabitants of their illusory Eden as they pass him by – pinching the nipples of a shepherd, slapping the butt of another, crudely grabbing the crotch of a nymph as he strokes his own. At one moment, he even kisses Acis full on the lips, so hungry he is for love of any sort.

But there are also curious problems with Morris’s Polyphemus, who became the central character in this production. There is no indication that he is a one-eyed Cyclops for one. In the brilliant version of the opera presented by the Boston Early Music Festival a couple of years ago, Polyphemus, also sung by Williams, wore an eye-patch – a simple but effective solution to the problem that there aren’t a lot of one-eyed bass-baritones skilled in the Baroque repertory available. And the scene of the killing was so subtle that I doubt that anyone who didn’t know the story beforehand knew what had happened. I knew the story, and I didn’t see any sign of Polyphemus hurling a rock at Acis. A friend later told me that a nymph who rolled across the stage represented the stone. (?) These are faults of Mizrahi and Morris that undercut the work’s drama, which, befitting an 18th century pastoral, is slight to begin with.

The orchestra and chorus under McGegan’s direction, played with style and passion. Mizrahi’s costumes came as close to one could imagine nymphs and shepherds would wear. (But although he created a handsome suit for Polyphemus, one I can imagine Williams wearing to the next Met Costume Gala, he failed, as I’ve already mentioned, at creating a visual sign that he was a Cyclops.) The sets by Adrianne Lobel effectively used the vocabulary of second-generation abstract expressionism – think Joan Mitchell - to create the sense of an Edenic garden. And Michael Chybowski’s lighting design created shadows and sunspots when required.

The vocal quartet was of mixed quality, which seriously compromised the success of the entire endeavor. Although totally unbelievable as a sea goddess, soprano Panthaki sang well with the bright, clear style of a Baroque specialist, with some rich low tones, although she was disturbingly sharp at times. As her lover, Cooley’s tenor was smooth, sonorous and loud – which was a blessing since so much of the singing faded away in the Shubert’s weird acoustics with its dead spots. As Damon, the wimpy Don Ottavio type tenor, Zach Finkelstein was so audibly weak most of his limited time on stage that he made little impression. (He might very well have been standing in some of those dead zones.) A shame because he had one of the loveliest arias in the score, “Would you gain the tender creature,/Softly, gently, kindly treat her,” his ignored advice to Polyphemus. It sounded appropriately sweetly voiced but it was hard to hear even though I was sitting only a few rows from the stage.

Williams, a regular with Boston music organizations, although his Playbill bio downplays them – is it more prestigious to sing the Messiah in Houston than to star in operas by Handel, Monteverdi and Charpentier with the Boston Early Music Festival?? – stole the show. Tall, thin and handsome, he was the one singer who mixed with the dancers as an equal. His Mizrahi suit and his slick hair cut made him look like the Don Draper of the ancient world. Which, of course, made his social and sexual dysfunction all the more disconcerting. One wanted to see him get it on with all the nymphs and shepherds and one wondered why Galatea rejected him in favor of the stolid Acis. Of course, Williams’s attractiveness, which Morris and Mizrahi emphasized, made his monstrousness all the more difficult to accept, although his boorish behavior reminded us that even a beauty can be a beast.

Williams also got two of the great pieces in the opera to sing – and he made the most of them. In his entry recitative, “I rage, I melt, I burn!” I half-expected his head to explode with his anger like Etna, the Sicilian volcano the character is inspired by. And the following aria, “O ruddier than the cherry,/O sweeter than the berry,/O nymph more bright/Than moonshine night,/Like kidlings blithe and merry!” he demonstrated that beauty of tone and fierceness of expression can be coupled with malevolent behavior. It was a highlight of the evening.

But it was not the brilliant evening I had wanted and expected. Too much of it seemed tossed-off. Morris is at the stage when he can choreograph a Baroque opera in his sleep, and some of this “Acis and Galatea” seemed as if it were dialed in. And, if he puts them together on the same stage, he has to learn to integrate his singers and dancers better. He needs to cast singers like Williams who hold their own visually and dramatically with his dancers. Such beings exist, he just needs to take the extra effort to find them.