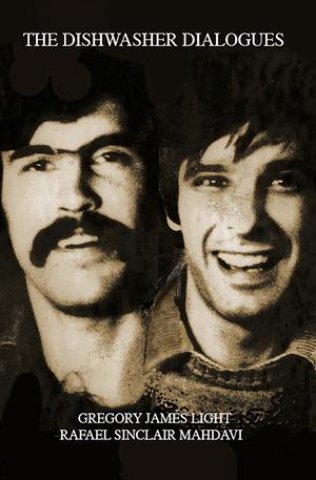

From The Dishwasher Dialogues

Parisians Sans Haute Couture

By: Greg Light and Rafael Mahdavi - May 18, 2025

From The Dishwasher Dialogues

Parisians Sans Haute Couture

LA SAGESSE DES CLODOS

Rafael Mahdavi: As I mentioned before, Chez Haynes was well heated, but outside of Chez Haynes, everywhere I felt the cold seep right into my bones.

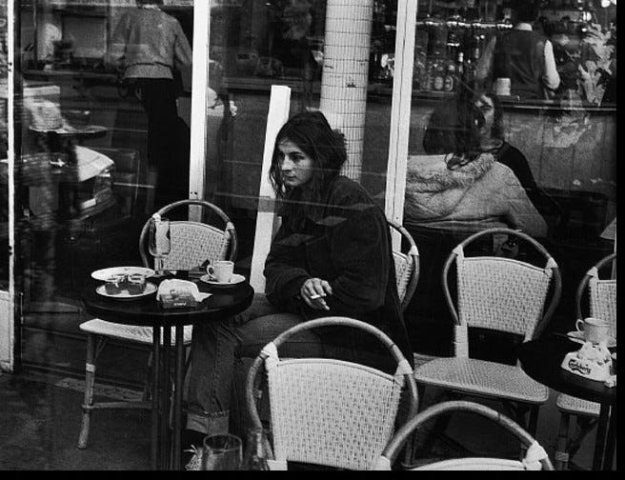

Greg Light: The local café was always a great place to escape the cold. Especially if the cold was accompanied by deep, penetrating rain. Warming up in a café with an espresso (never more than a franc) and people milling nearby, radiating their heat into the environment, was a surprisingly pleasant experience.

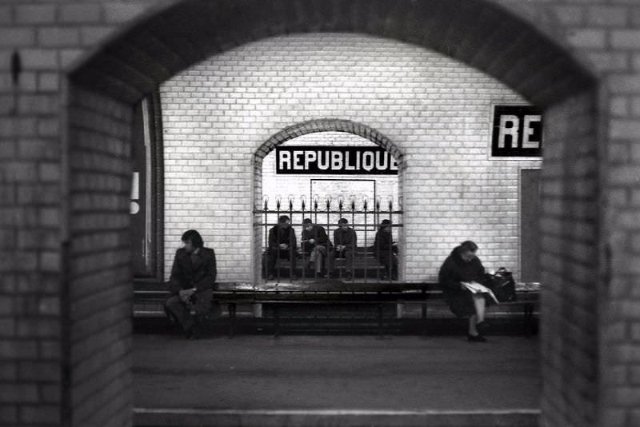

Rafael: For some couples, for the bums in the subway, each person could be a heating source for the other. The metro was usually warm when the stations were underground, and that’s why I never took the bus in winter. They weren’t well-heated. I felt for the clochards, les clodos–—the beggars and the outcasts, who spent the days in the metro. They would find a spot either on the station platform or in the maze of corridors in the big stations like Chatelet or Montparnasse or République, where they spread out their blankets and pieces of cardboard and hopefully, a plastic bottle of gros rouge, the cheapest red wine. They set up house for the day. And some clodos were couples.

Greg: They, too, had found the secret of ‘warmth’. People, shelter, a beverage of choice.

Rafael: They dozed in their wine-induced stupor, but they were rarely asleep, for they always perked up enough to say merci when somebody gave them something, a coin or a little food, a baguette or a sausage or a pâtisserie. The homeless dreaded the often-fatal hour at zero-forty-five, a quarter to one in the morning when the last metro rumbled through and the metro staff, often accompanied by cops, would shoo the clochards out because the station was closing. The metro staff would then pull the door-grills shut at the stairs leading up to the street. The bums would sometimes settle in for the night by the grills because warm air seeped out and up from the metro tunnels. I say fatal because it was for some. When the temperature sank below zero Celsius, the cardboard and blankets and shared bodies weren’t sufficient to keep them alive; often sick and always under-nourished, the clochards sometimes died, huddled by the grill gates of the metro, curled up in somebody’s arms. A few times I witnessed city officials, with vans from the public shelters, come and offer to take the homeless to a warm place, a shelter, for the night. Most of the clodos refused to budge.

Greg: Shelter came with some severe strings attached. I remember the city eventually rounded them all up once a month, or thereabouts, to hose them down and disinfect them.

Rafael: Yeah, that’s why some of the clodos had dogs with them. With dogs the cops couldn’t round them up.

Greg: Clever move. We could have learned more from the clodos. Like the homeless everywhere, there is often wisdom, sagesse, there.

Rafael: The clodos insulted the officials who tried to help and got in a good attack on the president of the republic––‘have you seen the president’s shoes, his fucking suits and ties, do you know how much they cost, enough to keep me going for a year, and you’re offering me a fleabag hotel?’

Greg: It wasn’t much of an offer from the city. A decent pair of shoes would have made a difference. Some of them didn’t have shoes, and the shoes the others wore didn’t look like they fit or were even worthy of the name.

Rafael: Shoes were a big thing for us too. They were expensive. Buying a new pair was a big event, they had to be affordable, a fancy word for cheap, and not just right for the winter but for the summer too. And how about a new pair of jeans?

Greg: Counting pennies, in this case bronze colored 5 and 10 centimes pieces, was second nature. It all added up. Making sure I had 40F for my carte orange and could pay my 500F rent at the end of the month was the goal. During the day, the metro was a godsend but sleeping overnight on its grates never looked that appealing. Everything else, including heat and clothes, fit in when and where possible. I remember oscillating between being one hundred francs up and one hundred francs down at the end of the month. If I went into the next month up, I was rich.

Rafael: In my apartment, the two electric heaters were never powerful enough. I dreaded the electricity bill at the end of the month. I didn’t want the power company to cut off the juice. That would be terrible. The windows in Parisian rooms were never double-glazed; this was a long time before the ecology issue became a global concern. Paris wasn’t built for the cold. Some of our friends had coal stoves in their apartments, and the metal tube-chimney snaked out the window. The coal was delivered in sacks and placed outside the door. Sometimes at friends’ apartments I would watch in admiration as the coal carriers huffed up the stairs with the sacks on their backs. The men’s faces were blackened with coal dust. And the dust permeated the apartment, and lighting the stove in the morning, my friends told me, was a messy ritual. Others, including me, well, we cheated, as mentioned before, we lived in fear that the meter reader would show up unannounced and the fine would be huge, and the cops might get involved. That’s why we spent so much time in cafes, mainly to keep warm. And at home I had extra blankets.

Greg: The coal men never went up the last flight of stairs in my building. No fireplaces in the servants’ quarters.

Greg: In any case, I rarely considered the weather a major cause of concern. Maybe that is the legacy of coming from a colder longitude and latitude. Plus, it rarely snowed in Paris in the winter. The weather didn’t interrupt transportation. Believe me, that is a major plus for a city. And there were some benefits. The hordes of fair-weather sightseers were gone. So, I was not immediately regarded as a tourist. Which was always irritating. And sometimes you could get too much of a good thing. I am thinking here of the summer of 1976. There was a huge heat wave that year. I dread to think how the clodos fared. No rain for months. And no such thing as air conditioning. Liter bottles of cold Ober Pils lager saved me. I remember going to an outdoor municipal swimming pool one day just to avoid the heat. It was packed with Parisians sans haute couture and fashion. (Speedos were never a good look.) At some point in the afternoon a few clouds unexpectedly appeared in the sky. Not rain clouds. Just clouds. Everyone in and out of the water suddenly burst into a loud spontaneous round of applause.

Greg: I don’t have any memory of a similar, unexpectedly cold winter spell in Paris. But, yes, I know there were some rough days, when I had my feet propped up in front of my little portable electric heater. Or when I went to bed with my clothes beside me under the blanket so they would be warm when I put them on the next morning. It was a frequent topic of conversation. I recall Laura and I discussing it more than once and in some detail. We compared the relative merits of heat and humidity versus cold and snow. She was from New Orleans and didn’t like the cold either.

Rafael: Warm clothing, which brings me to laundry.

Greg: Ahh, Laundry. Don’t get me on to laundry. That was always an issue. Summer or winter.

Rafael: When you don’t have money, you wash your clothes by hand, with cold water. You never take anything to the dry cleaner, that’s too expensive. I don’t remember any laundromats, but there must have been some. It would be an excellent place to hang out and keep warm.

Greg: I did go to the laundromat. Underwear and socks were washable in the sink. But the bigger items? You needed a machine. So, I went. Not often but when the odor reached a certain point. It was a bit of a hike and I learned early on you needed to have the right change. And lots of it. The washing machines took one-franc coins and the dryers sucked in an endless stream of 50 centime pieces.

Greg: The first time I quickly ran short of both one franc and half franc coins. So, I slipped next door to a café. I politely asked the cashier for change for 5 francs.

‘Bonjour Madame. Est-ce-que vous avez de la monnaie pour cinq francs?’

‘Non, monsieur.’ she was instantly wagging her finger in my face. ‘Ce n’est pas une banque.’

‘Mais—’

‘Allez monsieur. Ce n’est pas une banque.’

Greg: I could see that her till was loaded with coins. I was not asking to make change for a 100 franc note. just a 5-franc coin. It was like asking for a few quarters and dimes for a dollar. But I suppose I was pushing the boundaries, asking for a small courtesy; less effort than it took her to tell me the café was not a bank. Maybe she was performing street art. À la Magritte. ‘Ceci n’est pas une banque’.

Rafael: Do you mean the famous “Ceci n’est pas une pipe”? In French argot une pipe is a blowjob.

Greg: Yes, that was the reference. Without the ‘pipe’ part. She never offered me that either. Next door in the launderette, I put in a little more soap and doubled the load in an already stuffed washing machine. For the next day or so, my clothes hung from my pull-out shower, from bookshelves, window handles and on a barely working radiator. She saved me a dollar or two, so maybe she did me a favour. She certainly reinforced my sense of liberty to behave however I wanted. Like the clodos. There may not have been much equality or fraternity in Paris, but liberty was running rampant.

NEXT WEEK: GET A ‘REAL’ JOB