Laos

Part Three: Vientiane

By: Zeren Earls - May 21, 2010

Through a frenzy of motorbikes, we entered Vientiane (pronounced “Vieng Chan”), the capital city of Laos, in the early afternoon. The rapid arrival of modernity was evident from the tangle of cables on telephone poles and English subtitles on all buildings — bank, bookstore, internet cafe, etc. We walked over to the Joma Bakery/Café to get lunch. This downtown self-service restaurant operated at a dizzying pace. I managed to order vegetarian lasagna and mulberry pie, and took my tray to an outdoor table to enjoy the sunshine. I ate quickly to join the buzz on the street.

It will not be long before Vientiane is like Asia’s other frenetic capitals. The city is a mélange of Lao, Thai, Chinese, Vietnamese, French, and American architecture, cuisine, and culture, giving it an almost-anything-goes flavor. The city has grand old buildings, along with a number of air-conditioned modern ones. From their appearance it is evident that the city has a large share of the country’s wealth, though only 10 percent of the six million population live here.

Our tour began in a neighborhood which was once the administrative center of French colonial rule. The Presidential palace, originally built as the French colonial governor’s residence, is now used for hosting foreign guests of the Lao government and is not open to the public. Nearby is the royal and Buddhist headquarters. Haw Pha Kaew is the former royal temple of the Lao monarchy, built in 1565 to house the Emerald Buddha, which was brought to Laos from Thailand. Today the Emerald Buddha is back in Bangkok. The building, no longer used as a temple, has been restored; its two main doors contain remnants of wooden panels from the original structure. The museum has famed Buddhist sculptures of the types common in Laos. Its beautiful garden is a peaceful retreat from the dust and heat of Vientiane.

Across the street is Wat Si Saket. Built in 1818, it is the oldest original temple in Vientiane. The temple contains a total of 6,840 Buddha statues in varying sizes and positions. The interior walls of the cloister surrounding the central sim, where new monks are trained, are filled with specially carved niches containing more than 2,000 small silver and ceramic Buddha images, most of them made in Vientiane between the 16th and 19th centuries. Today Wat Si Saket is home to the Head of the Lao Sangha, a Buddhist order of monks.

Our hotel, Don Chan Palace, faced a riverfront boulevard that ran right along the Mekong at the southern edge of the town. Vientiane owed its early prosperity to its location on the fertile alluvial plains on the banks of the Mekong River. The river is lined with reinforced dykes and a town wall built against overflowing waters; massive construction to develop the riverfront is ongoing. Many outdoor cafes with a view across the river to Thailand offer food, fruit shakes, and beer. Due to the intense heat in the high 90s, I opted, regrettably, to stay in the air-conditioned hotel during our free time, rather than exploring the waterfront.

That Luang, or the Great Stupa, is the symbol of the Lao nation and the most important monument in the country. The breastbone of the Buddha is believed to rest at this site. Built in the 16th century, the multilevel stupa represents the different stages in Buddhist enlightenment: the lowest level represents the material world; the second, the world of appearances; the highest, the world of nothingness. Restored by the French in the 1930s, the dome is covered in gold leaf. Buddhist visitors come with flowers, incense, and candles, and circumambulate the stupa clockwise three times: once for the Buddha himself, once for the scriptures, and once for the monks. Meanwhile, vendors on the grounds sell caged birds to passers-by, who pay to release them as a good deed.

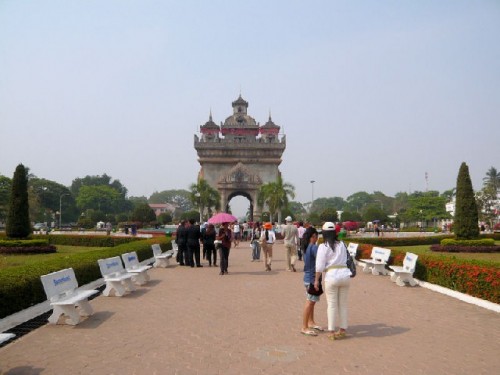

Patuxai (the Victory Gate) is Vientiane’s own Arc de Triomphe. It was completed in 1969 in memory of the Lao killed in wars before the Communist revolution. Inspired by the French, it incorporates unique Lao elements, such as Buddhist imagery in the moldings, and frescoes under the arches representing scenes from the Ramayana. Climbing the winding stairway to the top offered a splendid panoramic view of the city, including the government buildings nearby.

Talaat Sao, also called the Morning Market, is a mall where people used to shop before going to work; the name has outlasted the custom. The market is a maze of individually owned stalls selling everything from textiles to jewelry and household appliances, including goods imported from China, Thailand, and Vietnam. It is worth a walk through, though the experience is one of sensory overload.

A highlight was our visit to the Buddha Park, about 16 miles southeast of the city by the Mekong River. The park, also known as Wat Xieng Khuan, or the “Spirit City,” features a collection of over 200 large concrete Buddhist and Hindu sculptures amidst frangipani, the national flower of Laos. It was built in the1950s by a shaman priest, who merged Hindu and Buddhist traditions to develop a following in Laos and Northeastern Thailand. The numerous figures include images of Shiva, Vishnu, and the Buddha, as well as humans, animals, and demons, giving the place an air of fantasy. There is an enormous reclining Buddha, which is over 130 feet long. Dominating the park is a pumpkin-shaped massive structure with three levels, representing hell, earth, and heaven. It offers a good view from the very top, which is reached by a staircase inside the gigantic mouth.

On the way back from the park, we stopped by the river shore to see the Thai-Lao Friendship Bridge, completed in 1994 and funded by the Australian government. The bridge, which is ¾ mile long, connects Nong Khai in Thailand to Vientiane, and is symbolic of the opening of Laos to the outside world. Continuing on to a weaving village, we admired silk shawls with traditional designs woven on hand looms with tie-dyed silk threads.

In the same village we visited a local mor kwan (a shaman), to participate in a traditional Bai Sri Su Kwan, or rice-offering ceremony. Shamans are certified by the government and must display their certificates where they practice. We were received in a room with two framed certificates on the wall. We sat facing an altar prepared with flowers, candles, and food: hard-boiled eggs, small bananas, and banana and shrimp chips. Holding a lit candle in a plate in his hand, the shaman chanted in a Lao dialect, while we held on with both hands to white cotton threads tied to the altar. When he finished chanting, the shaman put a dab of rice wine in both palms of each participant’s hand, followed by an egg, and tied a white piece of thread around one wrist to be kept there for three days. Thus, we were all blessed to have a safe trip and to keep all of our 32 souls with us.

On our final night in Vientiane, we enjoyed dinner and a traditional dance show with live gamelan music at a downtown hotel. We checked our shoes with an attendant and sat on low floor cushions to eat. As in all previous establishments, the menu offered a great variety of Asian food; the program included both court and folkloric dance. The court dances were stories from the Ramayana epic, and the folk dances depicted daily lives, such as rice harvesting and fishing. Satiated both culturally and gastronomically, we returned to our hotel in anticipation of our trip to Vietnam the following day.

Long considered a backwater of Indochina, even during colonial times, Laos is changing fast. It is fully prepared to receive international visitors. The government sees tourism and related industries as a way to increase national development and assure a prosperous future. Laos is startlingly beautiful, is inhabited by friendly people, and has varied cuisine as a beneficiary of the French culinary tradition. In addition, its long tradition of Indic culture, the practice of Theravada Buddhism, and the rich mixture of ethnic populations with their diverse handicrafts make Laos a culturally rewarding destination.