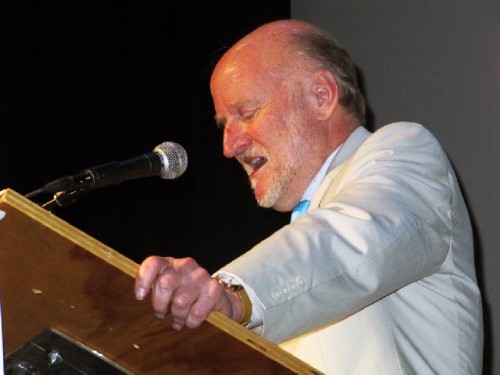

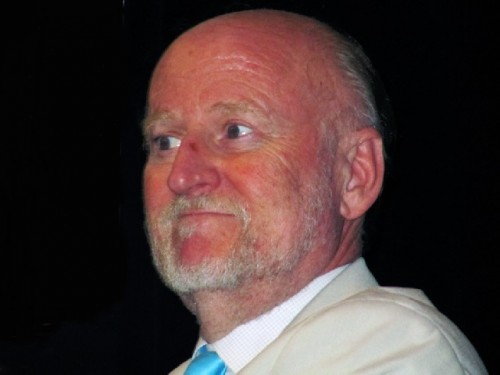

NEA Head Rocco Landesmann at Mass MoCA

Wrapup of Creative Communities Exchange

By: Charles Giuliano - May 21, 2011

Rocco Landesmann, who holds a PhD in theatre from Yale University and formerly was a successful Broadway producer, since 2009, has been the director of the National Endowment for the Arts.

Yesterday, during a lunch and awards ceremony that concluded the Creative Communities Exchange at Mass MoCA, organized by Berkshire Creative and New England Foundation for the Arts (NEFA), Landesmann was the featured speaker. He discussed a new initiative Our Town. As NEA head, he remarked with humor “I get to name things.” In this case a reference to Thornton Wilder’s iconic play.

He described visiting a huge but deteriorating space in Detroit that is being considered for renovation as a multi faceted arts center. Looking about at the well attended Hunter Center at Mass MoCA he noted the museum as a prime example of just such a renewal project. He referred warmly to some of the sessions he had attended that morning. He talked about networking and knocking on doors of other government departments, such as transportation, education, agriculture, all with deeper pockets than the NEA, as sources for extended arts funding. Quality of life falls under their redefined mandates and that opens up resources for the arts.

On this occasion, addressing a group of artists and arts organizations from the New England region, he refrained from dropping another bomb as he did in February. He sent shock waves through the arts community, and poured gasoline on the fire of Republicans and fiscal conservatives who oppose federal arts funding, when he applied the concept of Darwinism to the proliferation of theatres in the face of declining audiences.

As the New York Times reported in February- Speaking at a conference about new play development at Arena Stage in Washington on Thursday, Rocco Landesman, the chairman of the National Endowment for the Arts, addressed the problem of struggling theaters. “You can either increase demand or decrease supply,” he said. “Demand is not going to increase, so it is time to think about decreasing supply.”… He later defended his comments. “There is a disconnect that has to be taken seriously — our research shows that attendance has been decreasing while the number of the organizations have been proliferating,” he said. “That’s a discussion nobody wants to have.”

"Foundations and agencies like the endowment should perhaps reconsider re-allocating their resources, he said, perhaps giving larger grants to fewer institutions. “There might be too many resident theaters — it is possible,” he said. “At least we have to talk about it.” A group of Republican lawmakers called for the elimination of the National Endowment for the Arts and the National Endowment for the Humanities. Mr. Landesman said he was reserving judgment about that. “I think we have to see what comes out in the away of actual legislation,” he said. “I’m optimistic that the N.E.A. and the N.E.H. are going to be O.K.”

Pointing to the VIP table in front of him he thanked Mass MoCA director, Joe Thompson, who defended his controversial statements during a conference.

Following the luncheon we caught up with Thompson to discuss the controversy. They had met that day for the first time. Thompson told me that not long after the Landesmann remarks had caused a fire storm in the arts community it surfaced as a provocative topic for discussion and debate. While it is readily misunderstood and misinterpreted, and may have been political folly to come from the mouth of the NEA head, there is wisdom and concern in the essence of Landesmann’s message.

Thompson gave as an example a community that may have three struggling theatre companies. If they are competing for limited resources and audience share is it not better to have two or even one strong and successful company rather than three weak ones?

It is a question and debate that is readily applied to the Berkshires with a broad land mass, it takes an hour and a half to drive from one end to the other, a rural population of some 140,000, and a proliferation of arts organizations from world renowned to grass roots. All of these organizations are calling on the same tapped out funding sources. The major organizations suck up so much oxygen, particularly in a bad economy, four dollar a gallon gasoline, and such brutal competition for what Landesmann described as “butts in the seats,” that there is little or no breathing room for organizations on the lower end of the arts food chain.

This was precisely the challenge and theme that many of the forty sessions in the day and a half conference addressed. The organizers did a superb job of selecting a range of presenters telling the stories of bringing the arts, as a transformative aesthetic and economic experience, to communities as large as major cites like Hartford, New Haven and Providence, or as small as Bellows Falls, Vermont.

As an organizer of the conference expressed the presenters were generous in “sharing their secrets” and “proprietary information.” As a part of the format of the conference, the sessions were mandated to have handouts entailing cheat sheets of the presentations and to do lists. The prevailing message was this is how we are working with the arts and the creative economy, and here is a road map and template for how this might be applied to your arts organization, projects and communities. NEFA has also promised to keep us updated and help in facilitating future networking. Every session ended with time for networking which might be as simple as exchanging business cards with commitments to stay in touch.

Selecting just eight sessions to attend from the forty that were presented was like picking horses at the race track. You hoped that you chose winners. Of the eight I sat in on six were clear winners. Of the two that were less successful it was more about the delivery than the message. One issue is the reliance on power point. It is helpful to have bullet points on the screen but too much text, more than can be read in the time allotted, proves to be distracting. There is less emphasis on the delivery which just parrots the projected text.

Frankly, I prefer a presenter who engages the audience and humanizes the content then supplements that with a handout. Several that I attended were remarkable for warmth, wit and insight that enlivened the material. The unsuccessful sessions were marred by the insecurity of the presenter and lack of effective communication skills.

While I thought I had chosen well, it seems that I missed both sessions that received awards, a certificate, and unrestricted gift of $3,500 each. These projects were presented by Robert McBride of the Rockingham Arts and Museum Project (RAMP) in Bellows Falls, Vermont and to Margaret Bodell and Margaret Lamb of the City of New Haven, Department of Cultural Affairs, and their Projects Storefronts.

Yesterday morning, I posted the first report on the conference so I was rushing to get to the 10 AM opening session. I had chosen one but got pulled along by my friends Gail and Phil Sellers. Greater Concord Chamber of Commerce, Creative Concord, with Tim Sink, President, and Byron O. Champlin, Chair, Creative Concord, with the theme of leadership and partnerships, was terrific.

Their delivery proved to be charming and informative. Champlin spoke first, for ten minutes, then constantly interrupted Sink during his ten minutes. It got to be a running gag. But they provided many valuable insights about how to work with available resources and development in a city (Concord, the capital of New Hampshire) with a rural surrounding community.

They described the wisdom of working through the Chamber rather than a city government arts council. This puts the arts organization out of the roller coaster of politics and budgets. It allows for working with city resources while remaining independent. There was also a greater emphasis on forming business alliances.

The project they presented was the relocation of the League of New Hampshire Craftsmen which was formed in the 1930s and also has a large collection of crafts in storage. The facility they owned had fallen to neglect with little adequate space to show work. Until the intervention of the Chamber there had never been a capital campaign. The funding came from a large annual craft fair.

Through the efforts of the Chamber the League is about to relocate to magnificent space on the ground floor of a new commercial development in the heart of the city. The League will be able to sell its wares as well as have temporary exhibitions and displays of its historic collection.

As a part of the funding strategy the League will take on an educational role. They are launching their first ever campaign to raise $3 million. Part of that is selling tax credits to donors. By New Hampshire law, as they explained, if a business such as a bank gives $20,000 in cash, they get $80,000 as a tax credit and the League receives a $100,000 contribution. It is a win win for the donor and recipient. The League is now near its goal.

The developer is also building low and mid income housing immediately behind the commercial building. An increment of the 1,500 square foot units is being designated for qualified artists. This does not entail work space which is being developed separately. It begs the perennial issue of how to define an artist.

Many of the sessions raised the issue of attracting artists to urban and rural communities. There was pervasive discussion of how best to regard an artist. One common denominator is that an artist is a low income independent contractor. The issue is a need for affordable space, generally involving improving run down neighborhoods and properties, as well as marketing and peer recognition.

A rural setting may be great for finding space and creating the work but then there is the issue of financial support, most often through poor paying adjunct teaching and odd jobs. Then there is the challenge of finding successful galleries to promote and sell the work.

Artists residing in rural settings or marginal urban locations are most successful when they bring their reputations and income sources with them. It works best for established or senior artists. For emerging artists toughing it out with five roommates in a loft in Brooklyn is a better option for making it as an artist than hunkering down on a farm in Vermont. During the Hartford sessions there was discussion about attracting young artists to a city that falls on the axis between larger art markets in New York and Boston.

Providence, Rhode Island is home to Rhode Island School of Design, Brown University, and the renowned Trinity Theatre. There has been national media attention on arts related waterfront development. Stephanie Fortunato, a special projects manager, presented City of Providence Department of Art, Culture + Tourism: Transportation Corridors to Livable Communities; Building hubs for housing, jobs, and the arts around transit. She described the process of identifying the five most heavily traveled tourist corridors. Much of the information that focused on modes of transpiration, buses, parking, and destinations for arts tourism was complex and difficult to absorb.

During Q&A it was asked why Brown and RISD were not mentioned in the twenty minute presentation. They are on the periphery of the five routes which were discussed. A Providence based arts leader responded that they are very selective in projects that they support but “jump in gangbusters” in mandates such as arts education in Providence schools. Others in the audience spoke of the broad community involvement in the projects that were presented. With a large infusion of federal funding the project is described as work in progress.

For the past two years Diane Pearlman has been trying to establish one the nation’s few independent film commissions. Most are allied with states which provide built in funding sources. When The Fighter filmed on location in Lowell, for example, she described an economic impact that will last for years.

She was a part of the lobby that prevailed upon Governor Deval Patrick not to eliminate tax incentives for filmmakers in Massachusetts. She illustrated her point by describing film companies as scurrying off like “bugs” looking for locations and states offering the best incentives and deals.

When Hollywood scouts for locations in Delaware, for example, Pearlman described how ”They are met at the airport with a limousine.” In the film industry it is a matter of “location, location, location.” If they find the right setting a film company will find a way to make it happen.

But starting as mostly a one person operation in founding The Berkshire Film and Media Commission, based in Great Barrington, Pearlman has been stretched thin. She admitted that location research is not her strong suit and that she works with a consultant who she is trying to bring in full time as well as a development director. When BFMC organized its first benefit, several months ago, it meant round the clock work for four months. It eliminated family life and put a strain on resources to develop other aspects of the organization such as its website.

Initially she was under the umbrella of Berkshire Creative. Pearlman has now gone on to seek independent 501C3 status. She had experience running a studio when she relocated to the Berkshires several years ago. Part of her immediate task has been to identify and register qualified film industry talent in the Berkshires. It takes two professional credits to be listed on the website as a cinematographer, writer, director, set designer, or actor. For filmmakers considering working in the Berkshires, the website is an invaluable resource.

With four major theatre companies, and long off seasons, there is a critical mass of Berkshire based theatrical talent that lacks film credentials. Part of the mandate of her organization is to offer initially free workshops to learn the skills necessary to function on a movie set.

In addition to working on location Pearlman has struck a deal with Shakespeare & Company. About half of the space in a former athletic center has been developed for the Elayne P. Bernstein Theatre. The vast empty area is now being used as a studio for films creating sets for inside shots.

When Pearlman and others settled in the Berkshires many were specialists in post production and animation. They don’t have to be in Hollywood to pursue that work. But getting all of the Berkshires wired with high speed internet access is an issue. Pearlman commented that the pending improvement to the Pittsfield airport would present the option of a jet flying in Hollywood talent. So there are infrastructure challenges to developing a film industry in the Berkshires.

While the Berkshires present many spectacular settings and locations, with a range of thumbnails highlighted on the website, there is no way that shooting in Pittsfield can evoke a big city. But she is now in dialogue with two abutting counties. Pearlman and her board are in the process of abandoning Berkshire Film and Media Commission and rebranding as some variant on Western Massachusetts Film and Media Commission.

Using a map to demonstrate, she described how Bostonians view Western Massachusetts as anything beyond Worcester. Her thinking evolved out of a dialogue with a colleague in the Pioneer Valley region of Northampton and Amherst with its cluster of colleges. Rather than compete by forming yet another film commission, there was the suggestion to combine forces. Adding Springfield to the mix offers the option of shooting in an urban setting.

It would seem to be a nobrainer that expanding the mandate from the Berkshires to Western Massachusetts increases the critical mass of possibilities. It means having a lot more to offer and greater potential revenue for the film commission and economic impact in the region.

With an expanded base, through more productions, there is a better possibility of attracting greater film industry interest and media coverage. Landing a major film project will help to turn the corner for the region. Because of a string of recent hits, Boston, for example, has seen enormous growth of related unions and film professionals. Why not way out West?

That also entails organizational growth, marketing, staffing and expanded expenses. We asked Pearlman how she plans to address those needs. There was a concerned and pragmatic approach to seeking funding from limited regional sources.

Bottom line we’re all looking for an angel. Many of the strategies of this informative and superbly organized conference, hopefully, have wings.

Rocco Landesmann speech