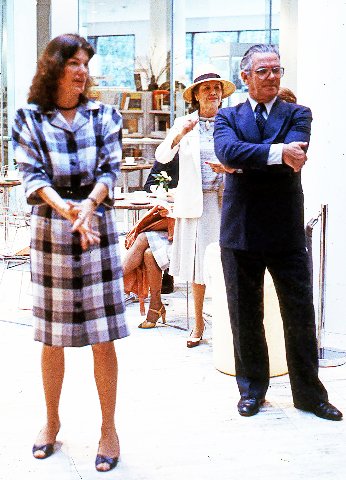

MFA's Jan Fontein Two

Addressing Issues of Racism in 1984

By: Charles Giuliano - May 21, 2020

Compared to other Museum of Fine Arts directors, prior or since, the Dutch born Jan Fontein, was particularly accessible. While appearing to be straightforward he could be devious. He was at times less than straightforward by witholding information and providing evasive answers to direct questions.

When I was investigating the museum's complex negotiations for acquisition of Jackson Pollock's "Troubled Queen" he sandbagged the story. He had the museum's PR director, Clementine Brown, call me at the Patriot Ledger. I was working with editor Jon Lehman to post our coverage, She asked what I was up to. We asked her to confirm that the museum was selling works by Monet and Renoir to pay for the Pollock. Instead of answering our questions, a professional courtesy of journalism, the story was scooped the next day by the Boston Globe. We ran a second day story. The Globe published an editorial that Sunday that conceded that it had been our story.

Brown betrayed what had been a long standing and close working relationship. It violated basic trust. By way of apology she later told me that Fontein was standing over her and insisted that she make the call. With the Patriot Ledger we continued investigative reporting on the fine arts in Boston.

Jan Fontein What do you want to discuss?

Charles Giuliano There are several points. How is the museum today different from what it was in the past? What was it before your tenure and how has it changed? When we last spoke regarding the reopening of the Evans Wing (of Painting) you said that “There will be many great surprises.” That has intrigued me.

JF Did I really say that?

CG Yes, on tape.

JF Good, so this is in connection to the Evans Wing.

CG I also want to consider the collections. In the past we have discussed the excellence of Asiatic, Egyptian, Classical and European and especially 19th century French painting. But there are problems to be addressed on modern and contemporary art.

JF Oh, uh huh.

CG The question is how to balance world class excellence in areas of depth compared to so many gaps in modern and contemporary art. How does the museum involve private collectors in building to the future? What is the relationship of major Boston collectors- Graham Gund, William and Saundra Lane, Stephen Paine, and Lois Torf- to the museum?

JF I would be willing to make comments on that question from our side although I am not so sure. Well, we will have to see how that goes as far as individuals are concerned.

CG Also, we can discuss what happens to the museum when you retire two years from now.

JF Two years from now!

(We spoke in 1984 and he retired three years later in 1987.)

CG By then it is anticipated that renovation of the Evans Wing will be complete and you will have fulfilled the mandates that you and Howard Johnson (board president) defined in 1975-76.

JF Did someone suggest that I am retiring in two years?

CG I have heard it discussed.

(Fontein was born 22 May 1927. When we spoke he was 57 and retired at 60. It is the norm for trustees to seek new and younger leadership particularly after major brick and mortar projects. Malcolm Rogers was 67 when he retired in 2015. Matthew Teitelbaum was 59 when he became director in 2015. He was surprisingly a year younger than when Fontein retired. The reaction of Fontein may entail that he had several more years to anticipate. It also reflects that there were concerns about his performance and reports of emotional board meetings. The general feeling is that the administration of Alan Shestack, who followed Fontein, was underwhelming. Shestack was 49 when he became director in 1987 but left in 1993. On his watch galleries were opened on a staggered schedule in response to budget cutbacks. He then served as deputy director and chief curator of the National Gallery of Art in D.C. from 1993 until his retirement in 2008.)

JF To take it out of personal context the job will not be completed until we have found adequate solutions to European and American Art and the Departments of Decorative Art and Prints and Drawings. We plan to put climate control into the entire building. When we finish the Evans Wing about half to two thirds of that goal will have been accomplished. So, the job will not be over when we finish the Evans Wing. Most people do not believe the task will be done until we have renovated the decorative arts galleries and storage. There is nothing more in need of climate control than European Furniture. It is true that the stone sculptures in the Egyptian and Classical galleries are in less pressing need of this.

CG Who will be the new curator of the Department of Painting? (John Walsh left to become director of the Getty Museum.)

JF That decision will be made (Peter Sutton) before your article goes to press.

CG In today’s Boston Globe there is an interview with (assistant curator for contemporary art) Amy Lighthill who is quoted “You can buy twenty Doug Andersons for the price of one work by Chuck Close.”

That raises an interesting question regarding collecting contemporary art. Does that mean that acquiring a work by Close is too expensive? Or does that mean that you will collect emerging (Boston) artists like Anderson? When you talk with Ken Moffett (contemporary curator) he says that the museum needs to acquire a work by Mondrian.

(In hindsight works by Close have increased in value while those of Anderson have not. Part of that comes from the fact that the MFA and ICA did not collect the work of emerging artists. Under Lighthill, there was an effort to do so and the value of those acquisitions, and those of Ted Stebbins, need to be revisited.)

JF That’s the basic problem. Boston’s 19th century collectors acquired the art of their time. That stopped around the beginning of the 20th century. We have a small Picasso “The Stuffed Shirts” from 1904.

CG There is also Matisse’s early “Carmelina” and the great Gauguin masterpiece. (His “D'où Venons Nous / Que Sommes Nous / Où Allons Nous” (1897-1898) was acquired during the Great Depression.)

JF They were much later museum acquisitions. The difference between 19th and 20th century collections is basically for one reason. You will recall the Picasso we bought recently. I bought it because I thought it was a wonderful picture. I bought it with the idea that it tells people what we want to do.

The problem is if there were a rich residue of paintings bought in Boston during the 20th century. If only there were Boston collectors we could go to and say please give us your great Mondrian or your great Leger. If they were in Boston this would be a problem with a very different dimension. The issue is that those collections do not exist. You have to acquire them from collections outside of the city or we have to buy missing works. Both approaches are now more difficult because of prices for those works. The museum would have to sink its entire resources into a program to do something like that.

We are, however, a great museum even without a Mondrian. The prices are so high for those missing works. There are some around and we have been considering the possibilities. On the other hand, last year, we got a masterpiece by Stuart Davis.

CG It was a gift from the Lane collection.

JF It was a bit more complicated than that. We acquired it with the Lane Foundation.

CG He also gave the museum key works by Arthur Dove and Frans Kline.

JF Yes, the Dove he gave us earlier. There are great persons who we know, people we all recognize as great individuals, but who have limitations in their character and knowledge. That doesn’t mean that they are any less great. The idea is that the museum tries to get as much as possible from many different people.

Works from the early 20th century have become so prohibitively expensive that the museum would have to give up all kinds of other things in order to get them. There are limitations to what a museum can do regarding concentrating its resources. There are issues that many outsiders who give us advice do not understand. Many of the funds that have been given to us are restricted. If we put everything we have into one basket, theoretically, we could buy a Mondrian. That so much is restricted means that relatively little is available. Even if we made all the necessary sacrifices, we would not be able to solve this problem.

CG When I interviewed Ted Stebbins (curator of American Painting) he said that “In the area of American art from 1900 to 1945, in the next ten years, I expect the MFA to be on a par with the Whitney and Hirshorn Museums which have the best collections of that period.”

JF I was talking about 20th century European art. In the area of American art we have a much better chance.

CG That’s a strong statement that Stebbins made.

JF Well, you know, Ted is a very optimistic person.

CG Is what he states a reachable goal in the next ten years?

JF Well, in that field we are ambitious. But I don’t spend time comparing us to other museums. I find that a little boring. Let me put it this way. When we reopen the Evans Wing the entire ground floor will have American art with the exception of one or two galleries. Do you remember those narrow corridors behind the lecture hall? The whole thing goes out and there will be a nice gallery there. Right in the core of the building.

We still don’t know which paintings will go where. It will be the first time in the museum’s history that we have equal billing of American and European painting. I think there are chances of having American art more fully represented than European art. Of course, we have some very good European paintings.

I went to the exhibition of late Picasso at the Guggenheim Museum. (Picasso: The Late Years, 1963-73, 1984) Have you seen the exhibition? From that period, we have “Rape of the Sabine Women.” From the moment I became director people have advising me to sell or trade it. I don’t do that often and only when there is a really good reason to do so.

That painting, in the context of the exhibition, was exceptional compared to other works of that period. It’s really amazing. I think you know me well enough that I don’t brag. Or comment this this or that painting is better or worse than another one. I must say that when you visit that exhibition it is amazing to see. A colleague told me that “Rape of the Sabine Women” is to the late period what “Les Demoiselles d’Avignon” is to the early period.

(I saw the exhibition and do not share Fontein’s enthusiasm for the late Picasso. His point it well taken that the MFA painting is better than most work of that period.)

CG Was it Mr. Rathbone who said that to you?

JF No, but you have to give it to him. It was another colleague who said that. What came after “Les Demoiselles” is no doubt more important than was followed “Sabine Women.” It is however, head and shoulders above the other late work. So, we now have an early Picasso and a late one. If you have to have a late work why not have one of his best?

CG I have just returned from a visit to D.C. including the National Gallery and Hirshorn Museum. In NY I have spent time at the Metropolitan Museum, MoMA, Guggenheim, Brooklyn. The Art Institute of Chicago, The Philadelphia Museum, LA County Museum. Compared to which the MFA’s 20th century collections lag far behind. How and why is that the case? What can be done about it now that the 20th century is nearing its end?

JF Regarding 19th century paintings in our collection many Bostonians acquired and bequeathed them to the museum. The 20th century is different because nobody in Boston was collecting that work. It’s a complex sociological problem.

There is something of interest to mention. There is the Lane Collection exhibition about which we are very proud. It has been a chance to show many artists who have never been seen here. It hadn’t been a blockbuster but there has to be more to it than that Bostonians didn’t collect them. Boston came very late to the notion that something should be done. Even when I bought the Picasso there were lots of people who said why should we get into this? I was just starting this job and I may have been too optimistic. I wanted to buy it because I thought it was a terrific picture and it has held up very well. In the MoMA Picasso show it went well with the other work.

CG They didn’t borrow the MFA’s late Picasso “Rape of the Sabine Women.”

JF No, but that may have been a mistake. I don’t think the MoMA show (Pablo Picasso: A Retrospective, 1980) did very well with the late Picasso. When they (MoMA) see that painting in the context of the Guggenheim’s (late Picasso) exhibition they may change their mind about it.

CG Didn’t the MFA pay something like $150,000 for the painting?

JF It was way before my time (acquired by Perry T. Rathbone and Hans Swarzenski) and I know that it was controversial. Do you know Matisse’s seated nude?

CG “Carmelina” (1903)?

JF Do you know it was controversial when it was acquired?

(Provenance: By 1912, Bernheim-Jeune, Paris 1931, sold by Baron Shigetaro Fukushima (b. 1895 - d. 1960), Paris, to Pierre Matisse Gallery, New York; 1932, sold by Pierre Matisse Gallery to the MFA for $10,050. Accession Date: February 4, 1932)

It was acquired over great resistance from very conservative trustees.

(One of whom resigned stating that he could no longer bring his wife and daughters to the museum because of that nude painting. It is cited as the point when, as policy, the museum’s trustees abandoned the pursuit of modern art at a critical time.)

CG In (Walter Muir) Whitehill’s “Museum of Fine Arts: A Centennial History” (1970) he quotes the Asiatic curator (Ananda Kentish) Coomaraswamy (1877-1947) as stating in essence that the only good artists are dead ones. As policy, a great encyclopedic museums like the MFA should not acquire work by living artists.

(The Louvre, for instance, only acquired works by James Abbott McNeill Whistler, Henri Marie Raymond de Toulouse-Lautrec-Monfa, and Winslow Homer while the artists were alive.)

JF Well, Coomaraswamy was always ready with a good quote. Did you know that he tried to start our photography collection?

CG Do you mean the prints by Alfred Stieglitz?

JF Uh huh. That was a very good basis to start our photography collection.

(Georgie O’Keeffe, a friend of the curator, donated prints, including many nude studies of the artist, by her deceased husband, Alfred Stieglitz. They were “lost” for many years and eventually discovered in a bureau in the museum’s basement. Our interview with photography historian, Carl Chiarenza, revealed his role in finding the treasure trove.)

CG Can you shed light on why the trustees turned down the acquisition of the Jackson Pollock masterpiece “Lavender Mist?”

JF I honestly don’t know.

(This was discussed in our interviews with former contemporary curator Kenworth Moffett.)

CG This was a great mistake. As one of his greatest works Moffett got the collector Alfonso Ossorio (an assemblage artist with Cordier Ekstrom Gallery) to sell the work for under a million dollars.

JF It went to Australia?

CG No. That’s “Blue Poles.”

JF Well you know, let me tell you. While there may have been a mistake, there are too many instances and too many individuals in all this. You can’t sit back quietly and point an accusing finger at any one person. No one person is responsible. The climate in Boston has changed.

CG What part have you had in that change?

JF Let me say this. The institution has evolved to such an extent that it can never go back to what it was.

CG Can you discuss that change?

JF It is difficult to discuss because in a way I have also changed. I know for sure, you know, that when I came, every once in a while, you know, because I know very well my own faults about this, have very much changed. I felt from the beginning, when I came here you know, having come from a European state, government-funded museum. People just come in, pay admission, look at pictures and don’t develop any relationship to the museum.

Here you have all kinds of different people at different levels who are interested in the institution. It’s a great mistake to assume that only takes place at the august level of trustees.

Peabo Gardner works here. (An intern in American Painting under Ted Stebbins.) His grandfather was one of the museum’s most prominent trustees for many years. The sign painters for the museum, the McQuaid family, have worked for the museum over four generations. They have felt the same pride in the museum, a proprietary interest, the very same as some of the brahmin families have for the museum. It is something that the museum inspires. That kind of feeling. You don’t have to be a trustee to have that feeling. One can be a carpenter working for the museum.

CG But you are different from directors of major museums who are generally aristocrats with great social status. Did it surprise you to become director?

JF I never intended to become director. I felt I would always be curator of the Asiatic Department. Once I got over the shock, I made a very deliberate effort to make sure not to bring my curatorial ideas to the position. The institution needs someone who can look at the whole picture. As far as changes are concerned let me mention a few. The city has changed. How long have you been here?

CG I’m a native Bostonian. Similarly, who would have thought that Ray Flynn would become Mayor of Boston? In that sense you are also a populist.

JF I find some of the things that the mayor does very interesting. He’s giving the people a message. I have a great affinity with outreach. Boston is a difficult city in which to be mayor. I wouldn’t like to be in his shoes.

When I came here all of the people connected to the museum went away for the summer. Families commute to The Cape and North Shore. After Labor Day they would all come back to the museum. It was part of an annual cycle. We started to have summer events. Fifteen years ago, if you tried that nobody would come. Five years ago, we had a summer opening and crowds came. Not nearly as many people were away as in the past. They were very pleased that something was going on at the museum. Our jazz concerts were a wild success last summer. We will certainly continue that this year.

Younger people, both husband and wife, are working people and professionals. That makes it difficult to get away to the Cape. They will take a vacation together but not the two and a half months as it was for families in the past. That’s no longer in the cards.

So there have been season changes for the museum. Almost all large museums have seen their audiences grow in the past ten years. Here that growth has coincided with the launch of the West Wing. In many ways the museum is less stuffy than before. As director I can stimulate that by example. I don’t know how well you know Chuck Thomas, our director of membership? Don’t underestimate the role that people like that play in this.

CG Your father was a psychologist or psychiatrist or something like that.

JF Yes.

CG You grew up in an insane asylum.

JF It was an institution that dealt with human abnormality. All kinds of abnormalities from criminal psychopaths.

CG That seems like the perfect background for a museum director.

JF When I was a young man I wasn’t interested in that kind of work. I didn’t like the way in which all those crazy people impinged on our family life. We lived in the middle of this institution and they walked in the garden and in our house. Yes, yes it was most unusual. It has given me a greater understanding for that side of human nature. Every once in a while, something happens that it must have been a valuable experience. The opportunity for understanding unusual opinions. Because that is what I think you are referring to when you talk about the museum. It has more to do with my temperament than upbringing. (laughing ) You may have more of a problem with that than I do.

There is a great deal of variety among museum directors. I think you have been taken in by Philippe de Montebello (Metropolitan Museum) as a paradigm of a museum director or J. Carter Brown (National Gallery). You see one type while Sherman Lee (Cleveland Museum) is quite different. Sherman is more the tweedy, pipe-smoking type. He has the time for that as director of a museum with a very large endowment.

CG Isn’t a large part of the job meeting with and courting wealthy individuals, patrons, and collectors? Doesn’t that entail competition with other museum directors? Particularly when trying to secure major traveling exhibitions?

JF We have tried to avoid that by developing our own shows. For example, what the print department does. We have developed a very special kind of audience. The photography shows we do are of unique quality. Or our show, A New World: Masterpieces of American Painting 1760-1910, which is now in Paris. (1983-1984, The Corcoran Gallery of Art, Museum of Fine Arts and the Grand Palais, Paris)

CG How is it being received?

JF It’s too early to say. It opened a few days ago. The press comments are fantastic. We were the first museum to show American painting in China. Now we have an exhibition of American painting in Paris.

CG In my review of the exhibition I noted that it did not include images of or by blacks or Native Americans.

JF I saw that.

CG There are in fact images of blacks but not in a fair and flattering manner. By luck you happened to be there when a group of Boston’s African American artists came to protest.

JF That wasn’t entirely luck. During that exhibition I was here most of the time. But I think the situation might easily have gotten out of hand.

CG To your credit you handled the situation well. Might another museum director, for instance, have invited the protestors in to sit down over a cup of coffee?

JF I can’t say what another museum director might have done. I found it interesting, as a problem you know, I do think that given the fact that there were some choices of paintings, you could not by the furthest stretch of the imagination classify as masterpieces, you know, well as I told my staff, that fish bowl.

CG The Goodes. ( Edward Ashton Goodes, 1832-1910, “Fishbowl Fantasy,” 1867)

JF I thought it didn’t fit into the theme of masterpieces.

CG As I pointed out in my review.

JF In view of that, I thought there was every justification for them (protesters) to asked for a work by (Henry Osawa) Tanner (African American artist, 1859-1937) to be included. Once we decided on including Tanner we had a great deal of difficulty getting the right one.

CG I understand that Bill Cosby turned you down.

(The entertainer has a renowned collection of African American art including work by Tanner.)

JF It is a difficult problem in that these people who are so important in the entertainment world often find a lot of people who volunteer information for them. I never personally talked to Cosby about it so I can’t comment on his motivation.

CG He called a press conferences regarding the matter.

JF Well, but he wasn’t there himself. I think, in all fairness, many entertainers have a particular urge to get involved in fairly hot controversies.

CG Were you surprised when this controversy surfaced?

JF Before that I had received one letter. But it’s the same thing in this letter you know. There are people you know who count. There was only one work by Mary Cassatt in the exhibition. Then there were comments about excluding Hispanic and Asian American images and artists.

CG There are no works by George Catlin (1796-1872 notable for his paintings of Native Americans).

JF Well, let me tell you. There are all kinds of things about this that people didn’t understand. I don’t know if you realize that the show was originally planned to be just for Paris. It was the French who were concerned that the show would be too much about cowboys and Indians. For that reason, we stayed as much as possible, you know, from that theme, you know, within reason.

CG In fact there were no images of Native Americans. The curators and museum directors should have been more sensitive to the notion of masterpieces and fairly representing American art and its social-political themes to an audience of Parisians. The resultant exhibition was narrow and biased. It is little wonder that African American artists protested.

JF It was decided that at some other time we would organize as show that emphasized the folk, native, and primitive side of American painting. And that those themes would be represented. The original idea was to concentrate on nine artists. That’s why (John Singleton) Copley (1738-1815) is the only 18th century artist included in the exhibition. The original concept, as is often the case, got watered down.

CG How can a great museum afford not to look at the political ramifications of a major exhibition sent to Paris representing the American people?

JF Our show that went to China was under government auspices.

CG This incident perpetuates the image of the museum as an elitist, autocratic institution. As I stated in my review this was the America of John Singer Sargent’s “Madam X (Madam Pierre Gautreau),” 1884, and not the American frontier.

JF Well, yes. But you have to understand that it was deliberately selected to be something like this. Somebody had tried to do a show of American Impressionism in Paris and it was a dud. It was clobbered by the critics.

CG But the Institute of Contemporary Art had a great success when it showed a survey of American Impressionism. (Under the director Stephen Prokopoff, 1978-1982.)

JF In all fairness the show was not well selected. To show American Impressionism in Paris invites being clobbered. How can you compare Frank Weston Benson and Edmund C. Tarbell to Monet and Renoir? Particularly in Paris.

(Benson and Tarbell were collected in depth for the MFA by Ted Stebbins.)

The representatives of the black community came to see us and assumed that we were unfamiliar with black artists. Some of the black artists that they showed to us were indeed less familiar to our staff. While they were important to the black tradition, they didn’t stack up to what we had in the exhibition. But, from the moment they proposed him, I immediately admitted that we should have included a Tanner. But I will tell you something interesting about him. Do you know which museum has five Tanners? Would you believe it, the Louvre.

CG Are there any Tanners in the MFA?

JF No.

(“Interior of a Mosque, Cairo” was acquired in 2005. “Street Scene, Tangiers” was acquired in 2011.)

CG I recently saw a Tanner in the National Gallery.

JF For that show we tried to track a Tanner that had been sold at auction. It was one that Bill Cosby bought. The whole experience for us, there is one thing that I should mention, that perhaps you will see as a mistake on our part. Which I think is a legitimate mistake. We vastly underestimated the impact that the exhibition would have.

It will be difficult to understand but I will be perfectly honest with you. The French asked us to do that for them. And I said, “Hm. Why shouldn’t we do that here?” We talked about that. Originally, it wasn’t even the idea. We weren’t working on a blockbuster. If you see what I mean. Once the paintings were here our estimates of attendance were far too low. And Ross (Farrar) my associate director, who never interferes in art matters. He walked into the gallery where the paintings were spotted. He looked around and in two seconds said “I increase the estimate of attendance by 50,000.”

CG What was attendance?

JF I have forgotten but well over 200,000 in a short period of time (September 7 to November 13, 1983). That was another thing, the timing was such that we could not have it here longer. The main thing that you have to keep in mind is that representatives of the black community couldn’t understand, and maybe it would be unfair to expect them to, is to accept it and understand it.

CG Overall, it seems that through negotiation with the community you handled the situation well.

JF Yes, compared to what could have been.

The staff had long conferences with them (the black community) afterward about it. It’s obvious that there were, even at the end, very substantial differences of opinion. In all cases we did not attribute the same importance to the tradition of some of those artists as they did.

It’s normal that everyone differs so why not we with them? But the main thing, you know, that people really don’t understand was that we had underestimated the impact that the show would have and treated it much more lightly, in a way, and all of a sudden, these thousands of people came in. It became this enormous blockbuster all of a sudden.

You could see that the people who came to the galleries were people who had been that they derived a certain patriotic pride from that. And you also have to understand that if we stand in there and say, hey isn’t that great. If the man on the street comes in and says “Isn’t this a blockbuster? It’s not European. It’s not exotic. It’s American.” That people like blacks that feel already, what shall I say, cut off in many ways from the mainstream of our society, that they have a negative reaction to that (traveling exhibition). But what they kind of misjudged is that we never had the arrogance of feeling ourselves as judges of American painting that said this one is in and that one is out.

CG You have to be very sensitive to those issues because of how the museum is perceived.

JF I realize that of course. But if you see it in the context of our own underestimation of the impact of the exhibition. If we had known that the show would have become that authoritative, we certainly would have given more, what shall I say, careful political consideration to the overall selection.

CG That’s hindsight.

JF Yes, yes but you learn from this.

(The question is how much the MFA learned from this 1984 incident and interaction with Boston’s African American artists and community leaders. A racist incident occurred between staff members of the MFA and a school group from the Helen Y. Davis Leadership Academy on May 16, 2019. The students were told that “No food, no drink, and no watermelon” were allowed in the gallery. The group also experienced racism and demeaning comments from other visitors during their tour. The museum reached a settlement of $500,000 negotiated by the attorney general. The agreement will “Make the institution more welcoming to all visitors, hire a consultant to assess and assist with the efforts, implement an anti-discrimination and anti-harassment policy for interactions between staff and visitors, and train its staff and volunteers on unconscious bias.”)

CG When we last spoke I raised the issue of the perception of the 20th century programming and collecting as having a narrow focus. Not long after that I visited the museum and was surprised to encounter the curator Amy Lighthill. Did you read today’s Boston Globe profile of her?

JF Yeah.

CG Her becoming a member of the staff has very much changed the outlook of artists regarding the museum. The museum is now viewed more positively. If you read my review of Brave New Work I expressed concern that the museum seemed to be looking for bargains rather than quality. What is the museum’s commitment and how did the museum create a position for Lighthill?

JF Well, ok, let me tell you. Obviously when I spoke with you the last time, I had already made up my mind. About what I was going to do but couldn’t say just yet.

CG Like not discussing the Picasso that was under consideration.

JF Well, yes and I can’t guarantee that it won’t happen again.

(I broached to him the art community’s dissatisfaction with Moffett’s narrow focus. A decade had passed for the contemporary program he founded. The need for a change of leadership was widely discussed. Moffett served from 1971 to 1984. John Walsh had been appointed by Fontein as curator of European Painting. When he left to become director of the Getty Museum there was a consolidation. Ted Stebbins became curator of American and European painting. He also took over what had been Moffett’s domain. For two years he aggressively collected American and European contemporary art. Lighthill reported to him. The next director, Alan Shestack, hired Kathy Halbreich then director of the Albert and Vera List Visual Arts Center at MIT to become contemporary curator. She soon departed to become director of the Walker Art Center. Her assistant Trevor Fairbrother took over as curator. During this transition Lighthill left the museum.)

JF When we spoke about it. (changes to contemporary programming) I had given it a great deal of thought. I honestly don’t recall if I had made a decision by then or not. But it really doesn’t matter because I couldn’t have mentioned it to you at that time.

Anyway, I did this for two reasons. I didn’t feel that an important decision should come out during an interview with you. We hadn’t made much of an announcement about changes. Right or wrong that’s something I have to take responsibility for and I’ll tell you why.

In such matters I simply feel that it is better to do something and then have people judge you by what you do. Rather that to make a statement and have people judge what you say. There has been so much talk about 20th century art. So, in a way, I thought I would continue this.

CG It was time for action.

JF I felt that we had to do something.