Major Installation by Jeffrey Gibson at Mass MoCA

A Prime Example of DEI Programming That Trump Hopes to Eliminate

By: Charles Giuliano - May 22, 2025

The vast, two-story vaulted gallery, the length of a football field, in Building Five of MASS MoCA represents an epic challenge for artists. The current iteration, which will be on view through August, 2026, has been created by Jeffrey Gibson (b. 1972) who is a queer artist of Choctaw and Cherokee descent. Gender and identity issues inform his explosive, colorful, rapturous installation “Power Full Because We’re Different.” This major commission flows from his work for the U.S. Pavilion of last summer’s 60th Venice Biennale. Now at mid career, he has ascended to the A list of American artists. It is a status that, until recently, has been denied to Native American artists.

Significantly, President Donald Trump cancelled a $50,000 grant for the exhibition which had been approved by the National Endowment for the Arts. The Gibson installation is emblematic of the Diversity, Equity and Inclusion (DEI) which the reactionary president and his neo-facist regime aspire to eliminate from all aspects of American arts/culture, education, government and commerce.

With hesitant steps I approached the first of two areas of the space. A pulsing, loud, disco beat with an emphasis on percussion represented a wall of sound that, with some trepidation, a visitor has to encounter, cope with, and penetrate. The work assaults us before we come to terms with and adjust to its frenetic pace and pulsing tempo.

The objects that are displayed verge on minimalist compared to the horror vacui of other artists who have tackled this challenge. The dense installation by Nick Cave is a recent example. Through conversion from a 19th century mill the resultant dimensions were more serendipitous than intentional.

As Tom Krens, MoCA’s creator, explained to me during a pre renovation walk through, it was his visionary decision to remove the second floor. That left a vast empty space flanked by two parallel rows of floor-to-ceiling windows. In an era before Edison, workers toiled from dawn-to-dusk by natural light. More than a century later the play of natural light is an element in a cathedral-like nave for contemporary art.

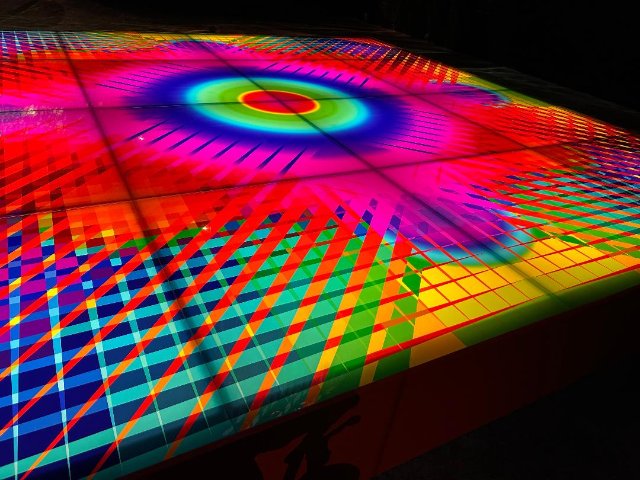

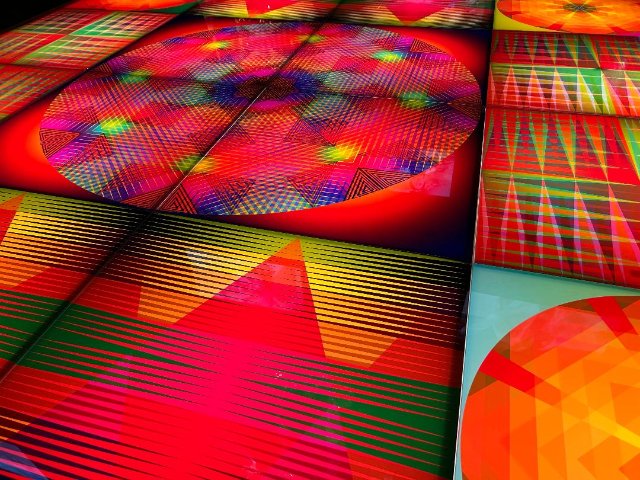

In the first of two spaces that Gibson has created there is a dazzling display of color through light that mixes with the pulsing sound. The content is somewhat sparse. Looking down there are several, square, raised platforms or dance floors. They are illuminated light boxes with Op art patterns of colored lines in kaleidoscope configurations.

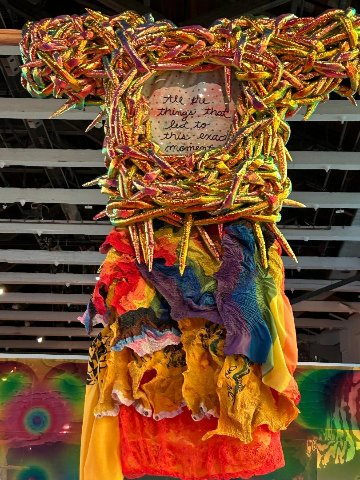

Looking up there are several dresses or costumes. There is a stick “hanger” from which they are suspended. Programmed to look up at them they articulate and mitigate the vaulted space taking on a sacred presence as ersatz vestments and garments to be venerated.

In that upper space are also a number of suspended video screens. Each one is articulated by a talking head or vignette, for example, clips from Dustin Hoffman in “Little Big Man.” A gay Indian offers to be his “wife.”

The inspiration and intent of the project is to articulate and express the concept of the “two-spirit,” a third gender that is both—and neither—male and female and is embraced by many Indigenous cultures. Some 20 individuals comprise these video vignettes. Given the general cacophony of the space, however, it is a challenge to extract more than a sample of that complex dialogue. During the run of the exhibition there will be performances and events that articulate an informational and educational mandate as well as a celebration of evolving native expression.

Some of these tropes are spelled out with expressive handwriting of poetic lines on walls and windows. These include Every Intersection Is a Broken Heart and I’m haunted by you or Sometimes your body changes and you don’t remember your dreams.

During the opening Albert McLeod, a human-rights activist and director of the Two-Spirited People of Manitoba discussed notions of two-spirit identity. “Spirit-naming is a historic tradition, and usually children receive a spirit name when they’re born. The implication is that the spiritual realm is benevolent to humans, so we ask for a guide for that child throughout their life, because there’s lots of brambles and wolves with sharp teeth. You need a spirit guide to help you, and there’s power in the belief that we, individually, are never alone, because there’s a spirit that walks with us for the rest of our lives.”

On another occasion he said “A lot of people think it (two spirit) refers to sexuality or gender, but over 34 years now, it’s more than that. For me, my community’s knowledge about history, tradition, language, and philosophy is [one] spirit. The second spirit is about love: nurturing for my siblings, my parents, my grandparents, my family, my community, and my Nation. It’s not so much about sex or gender, because those will always be part of the human experience. It’s about: what is that other level of knowledge or activism or energy that we need?”

The notion of two spirited or transgendered individuals appears in a broad spectrum of ages and cultures. It was an aspect of ancient Greek culture as related in the Metamorphoses of Ovid which I encountered recently.

Caeneus was originally a woman named Caenis who was transformed into a man by the sea-god Poseidon according to Acusilaus (6th century BCE). After being raped by Poseidon, Elatus' daughter did not want to have a child by him or anyone else, due to an unspecified vow or prohibition against it. To prevent this Poseidon transformed the maiden he had violated into an invulnerable man, stronger than any other. Achilles was enraged that his spear and sword were incapable of wounding him. Eventually, Caeneus was trampled to death by the centaurs whom he had insulted.

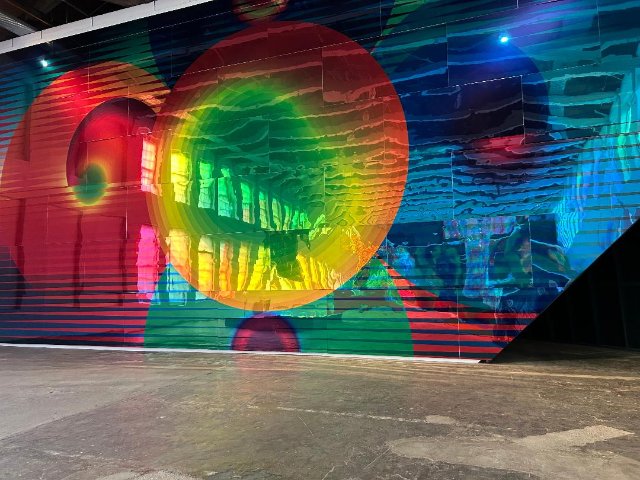

Through a tunnel we transition from the booming front part of Building Five to the silent back section. Again we encountered light box platforms and suspended garments. But this “quiet” space (in reality sound from the front spills over) is intended to be more contemplative and church-like. There is a play of natural light softened by patterned filters applied to the windows. Feeling less assaulted encouraged more engagement with the “sacred” objects. The stuffed-gold, serpent-like collar of one vestment reminded me of works by Kusama. The vestments suspended by “teepee poles” recalled the paint soiled smocks of Vienna Actionist Hermann Nitsch. These loose, boxy shirts were a by product of his expressionist blood splattered, drip paintings. They were displayed separately or configured with the paintings. Their manner of being shown was precisely like Gibson’s though the context is entirely different.

Behind a wall there was a large, split-screen video of Gibson performing with the gowns. They are staggered such that there is an interval that bifurcates our viewing experience. Both music and dance are free form. It’s better described as animated movement designed to augment the natural flow of the garments. The formatting is basic and more like early Dada films than the cutting edge of contemporary art. His whirling and twirling movement evoked those of the 19th century phenom Loie Fuller (1862-1928).

Other than spectacle I found no coherent narrative to the videos. In that sense they are more an action than a dance. A connection might be made to participants in a pow wow which locates Gibson within an indigenous tradition morphed as a kind of psychedelic experience.

Now 52, Gibson has had an unusual career. His tribe sponsored study at London’s Royal College of Art. The premise was that he would return as a teacher. I first encountered the artist when he showed at Camillo Alvarez’s Samson Projects. The first works I reviewed were brashly colored abstract paintings.

Not long after he founded Samson Projects in Boston's South End in 2005 we met for a beer and burger. In 2006 I reported that “Right now there is a lot on the plate of the painter/sculptor Jeffrey Gibson. At the time of the recent studio visit in Brooklyn works were partly crated in preparation for a move just a couple of blocks away. By the end of August he is scheduled to install a relief sculpture, the largest and most ambitious of his career, for a group show ‘No Reservations’ combining native and non native artists, curated by Richard Klein for the Aldrich Museum of Art in Ridgefield, Connecticut. There is a solo show on tap for Samson Projects in Boston this fall. He will be in a group exhibition in March 2007 ‘Off the Map: Landscape in the Native Imagination’ with James Lavadour, Emmi Whitehorse and Carlos Jacanamijoy, with an essay by Paul Chaat Smith, curated by Kathleen Ash Milby, at the Smithsonian’s National Museum of the American Indian in lower Manhattan. He is also scheduled to participate, this Fall, in group shows at the Westport Arts Center, in Connecticut, The Peekskill Project in New York, ‘Paumanok-a’ for SUNY, Stonybrook, NY and ‘Tropicalism’ at the Jersey City Museum. In addition, Samson Projects will continue to present works by Gibson in its grinding itinerary of national and international art fairs.”

Now creating biennial level works Gibson maintains a studio in Hudson, New York with as many as 20 assistants. He has deconstructed traditional tribal crafts such as basket making and bead work and expanded them to their current configuration. Arguably, that’s what it takes to compete at the highest level. It entails escalation of funding to do the work as well as aggressive marketing of the resultant product. Gibson is creating work at an industrial level.

Accordingly, the art world, gallerists, collectors, curators and critics are recalibrating their interest and commitment to Native American art. It was viewed as a breakthrough when Jaune Quick To See Smith (1940-2025) was the first indigenous artists to have a major New York museum retrospective (Whitney). It was seen as correcting the error of falsely according that honor to Jimmie Durham (1940-2021) who was alleged to have falsified his heritage.

Following his success in Venice Gibson joined the mega gallery Hauser & Wirth which will now represent the artist in collaboration with Sikkema Jenkins in New York. He will show with Hauser & Wirth in Paris this October and with Art Basel.

The representation deal means that Gibson will no longer work with Stephen Friedman Gallery in London and Roberts Projects in Los Angeles, as well as Chicago’s Kavi Gupta Gallery, with whom he had previously severed ties. (In 2023, Gibson filed a lawsuit against Kavi Gupta Gallery, alleging that it had withheld more than $600,000 owed to him.)

In the past few years, Gibson exhibited at the Aspen Art Museum in Colorado, the Sainsbury Centre in the UK, the Institute of Contemporary Art San Francisco, SITE Santa Fe in New Mexico, and the Portland Art Museum.

Hauser & Wirth’s prominence comes at a time when the most powerful dealers in the commercial art world play an increasingly large role in helping support New York’s ambitious museum shows. A New York Times analysis of solo exhibitions since 2019 shows that out of 350 exhibitions by contemporary artists, nearly 25 percent went to artists represented by just 11 of the biggest galleries in the world.

And within that tiny slice of the art market, the most exhibitions came from Hauser & Wirth artists, with 18 shows over the last six and a half years, outpacing even established names in the American art world like Larry Gagosian and David Zwirner.

The MoCA project following Venice is a highpoint of the artist’s career. “And just the way it so radically shifted how the space feels, it fills it with this pastel light that feels so soft,” curator Denise Marconish said. “It's very calming.”

“I have so much experience, so many years of working with color. I know how to make it activate,” Gibson said. “I can calm it, I can slow it, I can speed it up, I can make it vibrate. I feel really, it's really like music. It's like I can orchestrate color.”

Given the legacy of neglect, abuse and misinterpretation for Native American artists Gibson is taking a giant leap into a fraught and unknown future. It comes at a time of frontal attacks on DEI, culture, and our very democracy. This historic project at MASS MoCA resonates as a response to all that is being destroyed and repressed. Yet again, artists articulate the voice of reason. In that sense this is about more than just another exhibition.