Spring Awakening at Hancock Shaker Village

Borrowed Light Watercolors by Barbara Ernst Prey

By: Charles Giuliano - May 24, 2019

We were up early to arrive for the 9:30 AM press tour of Borrowed Light works by Barbara Ernst Prey at Hancock Shaker Village. There were a few people waiting for the 10 AM opening.

By the time we left it was surprising to see a packed parking lot on a week day prior to Memorial Day weekend. There were teachers and docents taking school children on a tour of the historic Berkshires landmark.

The famous gardens were in process of planting on a bright sunny day. The Shakers sold seed and other goods in a self sustaining and inventive manner.

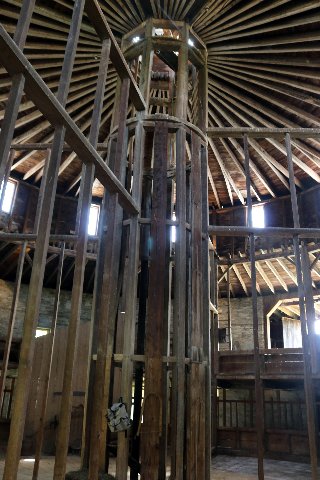

There was a ripe, earthy odor when we visited the unique and functional round stone barn. It is an icon of their pragmatic approach to form following function. In that respect their craft works, furniture, design and architecture are regarded by art historians as intuitive precursors of modernism.

We learned that there are just three surviving Shakers, from a woman in her twenties to an elder brother in his 80s, at Sabbathday Lake. The settlement is about a half hour from Portland, Maine. Arguably, described as a fundamentalist cult a core value was for men and women to share labor but not sleep together.

During the era of the Civil War various Shaker communities thrived. They sheltered runaway slaves and took in orphans. When adult they had the option of stay or move on. The Hancock site also provided housing for transient seasonal workers.

Their remarkable lifestyle, and vow of celibacy, was monastic yet secular.

With a mantra of “Hands to Work and Hearts to God” the simple, elegant “modernist” furniture and artifacts they crafted, and some 25,000 songs they composed, were all in the celebration of the Creator. Their every daily act from working the fields, tending to livestock, and preparing communal meals entailed a form of devotion and prayer.

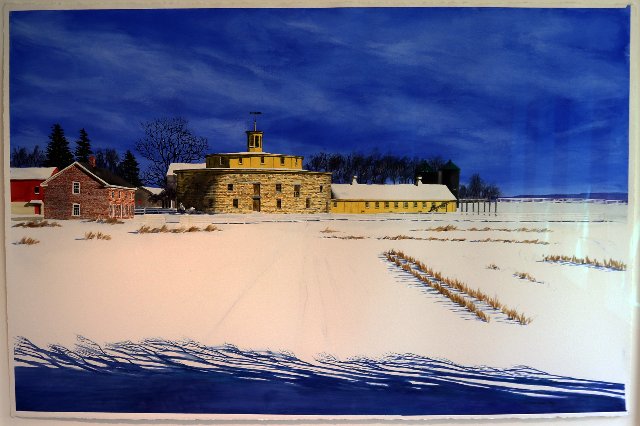

The watercolor artist, Barbara Ernst Prey, is a graduate of Williams College who has a studio in Williamstown. She discussed study with the legendary art historian S. Lane Faison, Jr. (1907-2006). In less than a year she has created a stunning series of large format renderings of Shaker interiors. One that differs is a winter view of the iconic round barn.

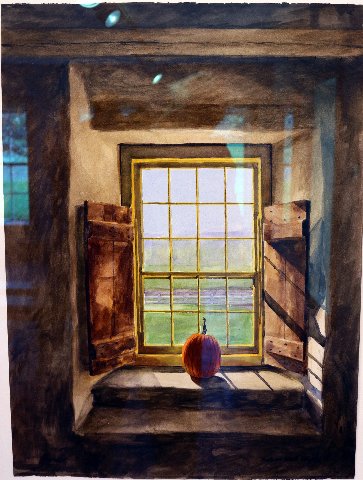

A commonality of the series, from simple to complex, is the play of light. The works are on view in the former Poultry House which has been renovated as a bright and pristine gallery with two large rooms.

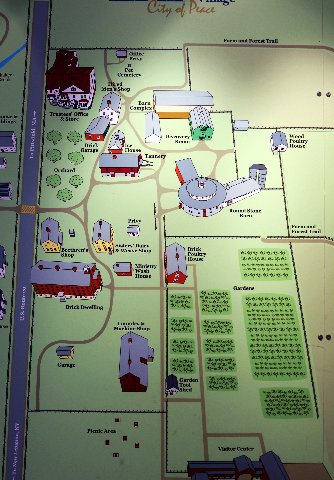

The director of Shaker Villiage, Jennifer Trainer Thompson, called our attention to many windows that surround the former chicken coop. In a pragmatic manner the Shakers viewed the play of light as spiritual and also encouraged contented hens to lay their eggs. A similar concept informs the round barn.

Trainer Thompson was a member of the founding team at MASS MoCA. The Prey project and exhibition is a part of the expanded contemporary programming that she brings to the institution. It has made Hancock Shaker Village a more lively participant in the diverse mix of major and unique Berkshire museums.

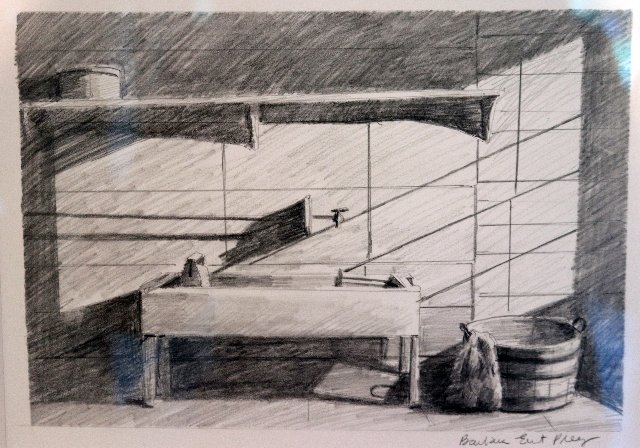

The artist stated that she has a lifelong interest in the Shakers. Starting in her twenties she collected Shaker objects and furniture. Making this work entailed a residency. There were initial small graphic studies then worked up as finished watercolors. To create the series in less than a year entailed what she describes as a “24/7” project.

The medium of watercolor is demanding and precise. Unlike oil paint which can be scraped down and reworked it does not allow for mistakes. The direct, sure, crisp and precise work on view is the result of decades of mastery. In particular, the artist, who has exhibited globally, is noted for richly saturated, intensive use of color.

A couple of years ago we first encountered her work during a press tour of the final phase of the build out of MASS MoCA. That wing of the museum ends like a ship’s prow with a two story window that faces Williamstown. The space has been configured as a resting area for visitors counting steps in a tour of the vast complex of buildings.

Taking up an entire wall in that gallery area is an enormous watercolor by Prey. It is a rendering of one of MoCA’s industrial spaces prior to renovation designed by the architect Simeon Bruner. The image, unchallenged as the world’s largest example of watercolor, reminds us of institutional history. It preserves the look of what was originally Arnold Print Works and then Sprague Electric.

In her practice the artist likes to conflate history, art history and fine arts. For this remarkable artist every picture tells a story. While visitors tour the very spaces which Prey depicts it is a way of allowing us to refocus on how an artist sees them. It is a boomerang of our experience and multi-layering of the play between reality and illusion.

The exhibition also enforces a shift in thinking by the director and board of Shaker Village. A question came up as to whether works by the artist are for sale and will they be purchased or donated to the institution?

Until now, Shaker Village has been mandated to store and preserve its fragile collection of a great range of Shaker objects. The works and their tradition have inspired many contemporary artists like Prey. Some years ago the Shakers were the focus of a project by the Institute of Contemporary Art, Boston. Artists were invited for residences at various Shaker sites including Sabbathday Lake. They participated in and did not disrupt the daily life of the Shakers. Artists assisted in preparing meals and did odd jobs. It was a part of how they absorbed the experience into work they created. The resultant exhibition by leading artists was diverse and remarkable.

There is a planned launch of a capital campaign. Trainer Thompson, who became director in 2016, commented that with an expansion of the Visitor’s Center and exhibition spaces that might be the moment to consider suitable storage for an expanded collection.

In Prey’s images there was surprisingly deep and rich chroma in depictions of garments. Given that they raised plants that were used as organic dyes for wool and fabrics was that accurate? Apparently, they were adaptive to industry and technology. From the many textile mills in the area they purchased bright, synthetic dyes. We learned that they were clever in business and produced products that sold well. That sense of entrepreneurship continues even today. The Shakers have always been self sustaining.

As a part of the research curators allowed the artist access to fabrics and objects in storage. In that sense her renderings are accurate if surprising. It is not intuitive to think of the Shakers as colorful.

We asked Prey about her approach to the medium. In particular what support did she use?. Was it Arches, double elephant paper? Yes and no was the answer as she ran out of paper and had to switch. The nature of the material was evident through careful observation of renderings on bright, cold pressed, smooth paper. The surface of watercolor papers has a great range from rough tooth to smooth.

Because the application of watercolor causes warping one approach is to stretch the paper prior to painting. Watercolor paper is measured by how much it weighs per 500 sheets. The heavier the paper the more it weighs and the more water it will take without buckling. The three standard watercolor paper weights are 90, 140 and 300 pounds.

Some artists favor rough, textured surface for loose, brushy, aqueous applications. Her approach is more precise in the manner of Flemish, egg tempera masters.

Viewing the range of work in the exhibition there are similarities and differences. The commonality is a play of light from windows. That entails crisp patterns and sharp lines through controlled execution. Compared to which, there is a refreshing freedom to the stone barn landscape. It would have been enjoyable to see more such views.

Most singular is the daunting detail of “Wood Work.” It is a complex study of the interior of the barn. When we visited the barn it was challenging to take it all in from a single position or view through a camera. Here the artist has seemingly addressed that issue with a compellingly clear, almost panoramic, horizontal cross section. In a sense it condenses her vast MASS MoCA view of an architectural interior with compressed but no less powerful impact.

Given the calming, meditative, stillness of the work it is no surprise that Prey earned a master’s degree from Harvard Divinity School. It would appear that in months of creating the Shaker series the artist labored in the vineyard of the Lord.