Michael Beatty at Barbara Krakow Gallery

Sculpture Featured on Boston's Newbury Street

By: Shawn Hill - May 25, 2008

PerimeterMichael Beatty

Barbara Krakow Gallery

10 Newbury St., Boston

May 24—July 1, 2008-05-25

http://www.barbarakrakowgallery.com

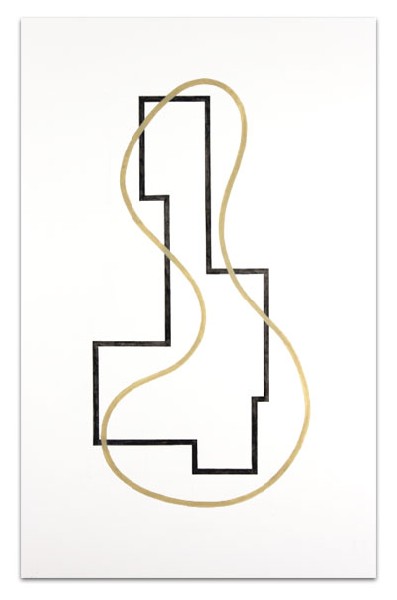

Dualities define Michael Beatty's sculptural output. Or maybe they're polarities. His drawings juxtapose two elements, one hard and geometric, the other soft and flowing. His sculptures mix two materials: wood and metal, in a dialogue that often feels like opposition. His all-wood sculptures take a different tack, focusing not on tension but on symmetry, emphasizing intriguing, mysterious organic silhouettes. Here the doubling is within one element, multiplied as in a mirror image, or a kaleidoscope.

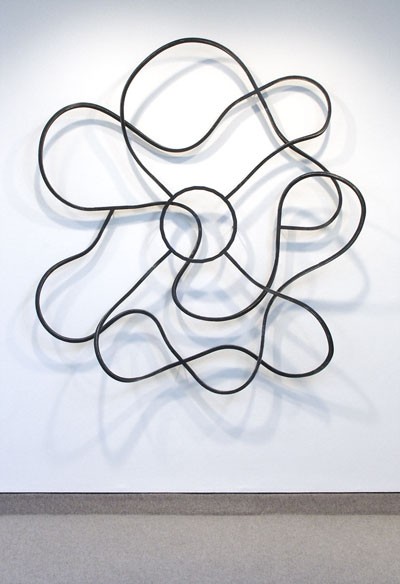

The steel elements that unite and anchor Beatty's flowing, curvaceous and linear strips of wood read like shackles, or at least clasps that need to be so dense and strong to tame that wild bent wood and hold it in place. The metal is dark, polished, and unbreakable, with a cold, vault-like sheen.

But it's also nimble and multifaceted in its own way. In "Even Keel," the dark metal performs a stair-like movement, bending at right angles in a sturdy progression along the wall (all of these works are wall reliefs), while the loop of white wood bounces and flounces along, a dancer's arabesque just flying down those "stairs." In "Full Circle," a loose, doubled interpretation of the figure eight (or maybe it's a Mobius Strip, as the four lobes seem to have no ending or beginning points) is held in place at the center by an H-shaped piece of steel. But that's only seen on end: up close, the cross-bar is actually a circle. Or, more accurately, a dodecagon, a 12-sided regular polygon. This intense, small little form seems like a battery charged with all the strength needed to keep the infinite loop of wood turning.

In "Here and There," we move up an order to a 24-gon, a large quasi-circular shape that seems to be the center of a flower of twisting black loops. The loops occupy a vaguely circular shape some 70" across, but the central steel polygon is the only actually symmetrical part of the piece. The loops of wood swing over and around each other, meeting at t-junctions at oblique angles, one darting wildly through the central element before arcing below and around to end Â… well, not to really end at all, as the loops keep using those custom joints to spring in new directions.

The drawings (and this seems self evident even after being told) juxtapose two shapes that encompass the same amount of area. The hard version corresponds to the steel, always in gray graphite. The soft component echoes the wood, that malleable organic element so masterfully controlled by Beatty, now rendered as kind of a single-celled creature or amoeboid form. Flattening things out somehow frees him to open a playful, cartoonish expressiveness. Are these pieces metaphors for reason vs. emotion, male and female, order and abandon? They seem to be two halves that make a whole, ultimately interdependent, like bone and flesh.

The non-metal wood pieces are beautiful but not as forthcoming. Based on brain scan imagery, they look more like decorative floral abstractions. The medical implications give them more weight, but that content is somehow at odds with their soft pastel colors and perfectly tooled structures. In fact, the sides and backs of these works are more interesting than their flat faces, making one wonder if there isn't some way to trigger more of a feeling of urgency or vulnerability. Beatty's own tendency to perfect finish and polished forms makes these pieces seem nearly too pretty to be vital.