Rising Currents: Projects For New York's Waterfront

Global Warming Solutions Exhibit at MoMA

By: Mark Favermann - May 25, 2010

Global Warming is a reality. Its implications over the long term are potentially catastrophobic. Little formally has been done to study the design options that will be necessary to solve some of the issues. Visionary folks at MoMA and P.S.1 have combined egfforts to develop workshops and design charrettes to look seriously at the situation as it will effect New York 's harbor in decades to come. The result is the current exhibit at MoMA, Rising Currents: Projects For New York's Waterfront, March 24 to October 11, 2010.

Though the national debate on infrastructure is currently focused on “shovel-ready” projects that will stimulate the economy, there is now also an important opportunity to foster new research and fresh ways of thinking about the use of New York City's harbor and coastline. As in past economic recessions, construction has slowed dramatically in New York, and much of the city’s remarkable pool of architectural and design talent is available to focus on innovation and creative problem-solving.

An architects-in-residence program at P.S.1 (November 16, 2009–January 8, 2010) brought together five interdisciplinary teams to re-envision the coastlines of New York and New Jersey around New York Harbor. The teams were each asked to imagine new ways to occupy the harbor itself with adaptive “soft” infrastructures that are sympathetic to the needs of a sound ecology. These creative solutions are intended to dramatically change our current attitude and relationship to one of the city’s great open spaces.

Curated and organized by Barry Bergdoll, The Philip Johnson Chief Curator of Architecture and Design, this installation presents the proposals developed during the architects-in-residence program, including a wide array of models, drawings, and analytical materials. A companion publication was written for the exhibition, On the Water: Palisade Bay by Guy Nordenson, Catherine Seavitt and Adam Yarinsky. It is published by Princeton University Press and costs $40.00.

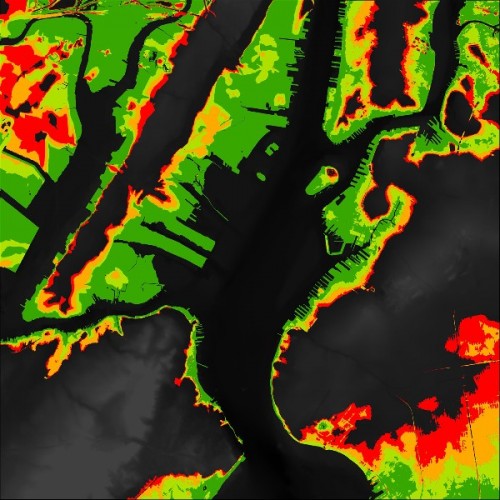

The New York City Panel on Climate Change has predicted that sea levels will rise some two feet within the next fifty years; in the last year, evidence of rapidly melting polar ice has led some scientists to predict increases between four and six feet by the end of the century. More frequent storm surges are also predicted. This project and exhibition Rising Currents was conceived in response to these threats. A jury of museum and design professionals chose five designers to assemble teams to study possible solutions for the region.

The teams studied five zones, including a wide variety of terrains: the heights on either side of the Verrazano Narrows Bridge, the low-lying lands of Bayonne and Jersey City (largely landfill), and the banks of the Gowanus Canal in Brooklyn. Teams worked alone and in collaboration but were not tasked with creating a master plan. They responded to the projections of climate change, and their visions of a resilient and vibrant waterfront do not necessarily comply with current landuse regulations or real estate interests but are creative solutions of wide applicability.

The teams were asked to consider a greater deployment of resilient, soft infrastructure instead of relying solely on the traditional, defensive infrastructure of levies, seawalls, and storm-surge barriers built by the US Army Corps of Engineers. Soft infrastructure includes restored wetlands that absorb water and slowly manage sea-level change, artificial islands that attenuate waves and thus can soften the impact of storm surges, and the exploitation of marine life—in particular the cleansing potential of oysters, once prevalent in New York Harbor.

The participating designers developed projects for five sites, identified and researched by engineer Guy Nordenson of Princeton University and his associates, Catherine Seavitt and Adam Yarinsky. Their study provides the framework for the teams’ development of adaptive and widely applicable infrastructure for the sites. The resulting solutions are on view in this exhibition.

The five teams opened their studios two times during their residencies, inviting hundreds of visitors to witness their work in progress and engage in debates about the future of New York. The entire project is documented online, at MoMA.org/risingcurrents, where visitors can join a conversation with curators, designers, and other experts. Each of the five teams had part of the 3rd Floor MoMA's Architecture and Design Gallery to present their ideas. Each team had a substantially different creative approach to solving the environmental challenges.

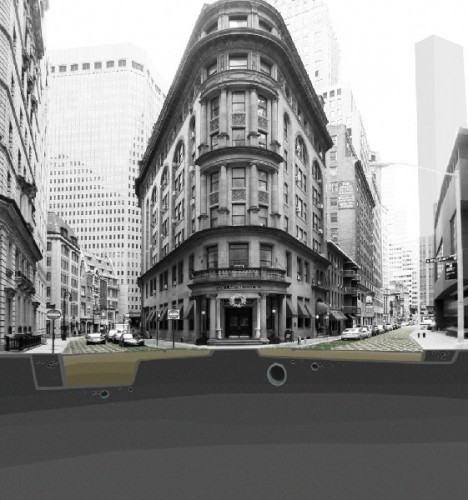

One of the more naturalistic approaches was by the group that called its project A NEW URBAN GROUND. The team included Team leaders Stephen Cassell and Adam Yarinsky, Architecture Research Office and Susannah C. Drake, dlandstudio Project site Lower Manhattan. Their approach was based upon natural considerations. Beginning in the 1600s, Dutch and English colonists in New York built docks to facilitate trade, fortifications to prevent attack, and seawalls to protect the growing city, gradually erasing the island’s marshy edges. Potentially the city’s modern seawall faces future sea levels and storm surges that it will not be able to withstand. Architecture Research Office and dlandstudio have proposed a new paradigm for city infrastructure in Lower Manhattan, combining soft and hard solutions. In this plan, downtown will be "greened" by the introduction of salt and freshwater wetlands, new parklands, and streets that have been reconceived as a kind of natural space.

According to their study, the history of urban modernization can be traced through streets, which perform key urban functions beyond surface transportation, such as the circulation and disposal of wastewater. In earlier periods, planners imagined streets as constructed machines, at odds with nature; in Architecture Research Office and dlandstudio’s proposal, Lower Manhattan will be paved with a mesh of cast concrete and plants that have been engineered to tolerate both soil and salt. This will create not only greenways but also an invisible underbelly of the city that acts as a sponge for rainwater. This new organic system will be poised to react to daily tidal flows and occasional storm surges. The new wetlands will provide an additional buffer against tides and restore the natural dynamics of the island.

Another thoughtful approach was by the NEW AQUEOUS CITY. It was led by Team leaders Eric Bunge and Mimi Hoang, nARCHITECTS Troject site Sunset Park, Bay Ridge, and Staten Island. The team included nArchitects and envisioned a future for the largest and most varied of the five zones examined in Rising Currents, composed of the heights on both sides of the Verrazano Narrows Bridge (in Bay Ridge, Brooklyn, and Fort Worth, Staten Island) and a low-lying area of Sunset Park, Brooklyn, to the north. New Aqueous City introduces a novel urban paradigm: a city that can control and absorb rising sea levels even as it accommodates an expected spike in population over the next century.

In counterpoint to an earlier generation’s infrastructure, embodied by the VerrazanoBridge, this project blurs the boundaries between land and sea, extending the city into the water. Habitable piers (with a new type of housing suspended above them) will be docking points for a network of ferries connecting the parts of the region. Manmade islands connected by inflatable storm barriers will encourage silt accumulation, fostering natural resilience against storm surges (and reinforcing existing storm barriers south of the Narrows). At the same time, water will extend into the city which will be punctuated by a network of infiltration basins, swales, and culverts to absorb storm runoff and function as parks in dry weather. Biogas-powered ferries and a new tramway will supplement existing rapid transit, part of a dynamic infrastructure that works with nature rather than against it.

The other three presentations seemed less cohesive and seemed to beg many of the more naturalistic features of the two best proposals opting for corporate or governmental regulation and change. Discordant notes seemed to theme their studies. There were other problems with the exhibit in general as well. As Princeton University academics framed the process, the resulting drawings, models and diagrams often seemed like graduate student thesis presentations rather than clear, direct visions for a major region's future. The exhibition was just too damn dense and often hard to understand where one study and approach started and another ended.

In addition, there was little human scale that seemed to indicate what was being proposed in a way that layman rather than scientists, engineers, architects or landscape architects could understand and comprehend. The drawings and models differed in scale thus making an overly dense presentation less readable.

However, even with its various faults, the notion of this MoMA and PS 1 study and collaboration is one that should be championed by museums and institutions who are interested in design and the ramifications of the built environment. MoMA should be congratulated for this effort and urged to continue this approach to design issues. This is an exhibit that makes us think about great issues and look at potential creative solutions in new and provocative ways.