Yigal Ozeri at NY's Mike Weiss Gallery

Maidens Cum Goddesses

By: Mary Hrbacek - May 25, 2011

In his recent oil paintings at New York's Mike Weiss Gallery, Yigal Ozeri explores personifications of youthful innocence, visualized as lovely young maidens cum goddesses. He situates them lingering in an iconic Eden, poised to confront the dangers and delights that womanhood encompasses.

Ozeri captures the essence of young girls seen in contemplation or at play, pondering their existence and surroundings, unaware of their true feminine nature. The subjects are viewed as angels or deities of unsurpassing purity, still in their stage of unconscious budding growth. In the context of the narrative, the enigmatic vision of a beautiful girl asleep in the sun stirs a sense of curiosity and sadness at the predestined “awakening” to come. Picasso found his muse in the numerous engaging women he aligned himself with; they became the core of much of his art. Ozeri’s art is similarly infused with inspiration by the mingled enchantment and melancholy he experiences at the bittersweet fate of his sublime muses.

Ozeri masterfully transforms the Southwest landscape into a universal terrain of the mind, where red replaces green in a hot alien zone. The redness accentuates the tension generated as the girls sprawl on the rocks; they dwell in a perilous state, in which impending desire threatens their peace of mind and tranquility. Many of the scenes in this new series evoke the end of the day, a time for departures, or for the onset of new beginnings.

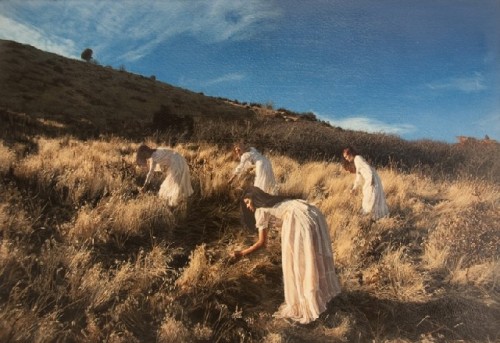

The mysterious female fantasy figures are clothed in white dresses, reflecting the play of shadows and light that accentuate the transient character of the elusive scenes. In one picture, the delicate lacy dress relates to the fragile seedpods growing around the girl, implying the onset of fertility. As her strands of hair capture the same light as the thistles, she becomes one with the earth, as does the recumbent girl in another picture, who sleeps in the afternoon sun, embedded in a field of dry grasses. Her bare thigh is raised and exposed, hinting at unconscious yearnings she experiences as she dreams.

Another figure whose head is wedged between two rocks appears to be pondering certain possibilities; light is dawning in her consciousness as she becomes aware of peril, of desire, of life on earth and its ramifications. A girl who sleeps in the sunshine seems to rest in the state of grace that defines the original Garden of Eden, before Eve sampled the fruit from the “Tree of Knowledge.”

Ozeri creates groups of one, three or four figures, in symbolically potent arrangements. The number one represents creation, which encompasses totality and unity. We perceive the spiritual genesis of the original Mother Earth. In one scene, the high horizon makes a solitary red-haired girl seem united with the field where she stands immersed in a thicket of reddish bracken. Her white dress and complexion stand out as spiritual beacons that contradict her impulse to yield to her inner nature.

For Pythagoreans, three portrays the notion of complete harmony, the fusion of unity and diversity. Heaven, Earth and humanity form another triumvirate. In a group of three girls, two sun worshipers sprawl with outstretched arms that express a sense of the illicit freedom to be had in the outdoors, while a third girl gazes furtively back to be sure she is unobserved. The number four denotes perfection; it relates to the seasons, the cardinal directions, and the four elements from Greco-Roman tradition. In one scene, the four figures picking grasses may be viewed as reapers, snatching grasses that are as ripe as they themselves are becoming. The universal underpinnings imbued in these images spark our realization of the meaning within the pictorial structures themselves.

The large paintings on canvas are reminiscent of Peter Weir’s film “Picnic at Hanging Rock,” where schoolgirls disappear under mysterious circumstances, apparently into the rocks themselves. Perhaps the artist is hinting that these pure females will also disappear, to be replaced by adult women. The small-scale paintings link the pictures in stature to historical masterworks by presenting them museum-style in cases, distancing viewers and protecting the pictures from harm. Since many masterworks display religious themes, with figures of gods, saints and holy men and women, the message seems to be that these spiritually infused images are linked to a similar though more personal tradition as well.

Ozeri’s paintings offer sensitive metaphors for the passage of adolescent girls as they face the dangers and the possibilities that growth implies, eventually becoming mothers. Their ethereal fleeting beauty temporarily transforms them into young goddesses.

The artist adds his signature vision of figures as they impact and merge with the terrain, to the explorations of those painters who have also engaged this iconic art theme. He seems especially inspired by the 19th century painter Eduard Manet, who molded the subject of the female figure in the landscape with his personal stamp. Ozeri captures that indescribable time in life, when girls verge on becoming the future.