Philharmonic Orchestra of the Americas at Alice Tully Hall

Alondra de la Parra Conducts Splendidly

By: Susan Hall - May 26, 2010

“Mi Alma Mexicana”

Philharmonic Orchestra of the Americas

Alice Tully Hall

Alondra de la Parra, Conductor

Daniel Andai, Violin

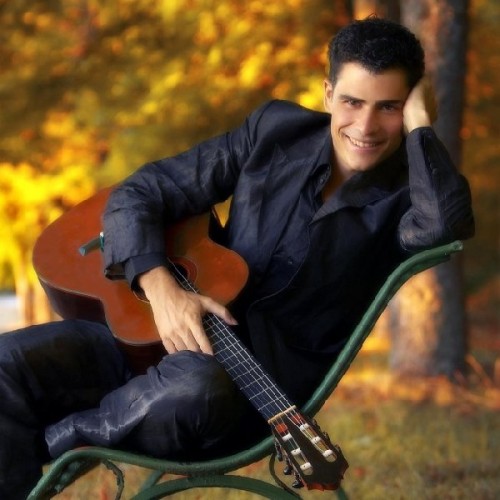

Pablo Sainz Villegas, Guitar

Melodia for Violin and Orchestra by Gustavo Campa

Intermezzo di Atzimba by Ricardo Castro

Concerto del Sur for Guitar and Orchestra by Manuel M. Ponce

Sinfonia No. 2 Federico Ibaar

Otono PorrenoInvierno Porteno by Astor Piazzolla (arr. Zhurban) Imagenes Cande Lazio Huizar

May 21, 2010

Alondra de la Parra brought her Philharmonic Orchestra of the Americas to Alice Tully Hall for an encore performance. She attracts an audience of mixed ages and hues, but is not one of the young music artists who rely on their own blown-dry hair to carry the evening. She announces that she’s hip with an elegant tux jacket with puffed shoulders and a fitted waist, skin-tight tux pants and pumps. But as she lifts the baton, it is clear that she is all about the music, attentively bringing forth the essence of the compositions she chose. She describes scrambling around the countryside and digging up scores in the cellars of the grandchildren of the composers. They express the Mexican soul. The occasion: the bicentennial of Mexico’s liberation.

Gustavo Campa‘s Melodia, played delightfully by the concert master, Daniel Andai, came right from Europe, clearly quoting Brahms and Schubert lieder. Music conservatories were opened in Mexico City in the mid nineteenth century, and focus turned away from local liturgical instruction to the European mainstream. Soon native Mexican traditions would be brought into composition.

The Intermezzo by Ricardo Castro is from his opera Atzimba, and recalls famous Mexicans, among them a native woman, Malinche, who assisted Hernan Cortez.

De la parra is twenty-nine years old, and formed her orchestra at twenty-four. Being a successful woman in the music world is even tougher in Mexico than it is here. Two ideas held a grip on Mexico for centuries. Machismo we know. Malinchismo grew out of Malinche story. Cortez abducted this young Indian girl and used her as an interpreter. Malinche helped the conqueror in his first parliaments with the Aztecs and then fell in love with him.

Today Malinchismo refers to an inferiority complex that crops up whenever a Mexican confronts a foreigner on important matters. It is especially obvious when a young woman consents to her employer's advances. De la Parra seems unperturbed by either Malinchismo or Machismo.

Manuel M. Ponce is recognized as an important composer for the Spanish classical guitar. His sound is colorful and sentimental, with opportunities for virtuosity. A rising star of classic guitar, Pablo Sainz Villegas, who played earlier this year with the New York Philharmonic, was compelling as soloist. Ponce also wrote a rich repertoire for solo piano, piano and ensembles, and piano and orchestra, developing the first period of modern musical nationalism, using Native American and European resources, but merging them into a new, original style.

Frederico Ibarra's Sinfonia No. 2 takes place in ‘a chamber of dreams.’ The epitaph for the piece ends with “A thud, trapped in the shell of my sleeping ear.”

Curiously, the sole woman whose accomplishments stood out over four centuries in Mexico, was Sor Juana Ines de la Cruz, a poet and a woman of high learning, who wrote that harmony was like a swirling shell. She could converse on equal terms with the wise men of her time on philosophical and theological subjects. A moving contemporary opera, “With Blood and Ink,” whose subject is Sor Juana, was performed recently at the New York City Opera’s Vox program.

Sor Juana's musical accomplishments took place in a convent where she taught herself music from theory books. written by Italians. Convents enjoyed certain privileges. Chapelmasters were needed for religious services, but men were not allowed in, so music schools had to open for young women preparing for the convent. If they showed musical talent they were taught enough music to be able to serve as chapelmistresses. Sor Juana wrote, “If memory fails me not, I said that harmony is a spiral, not a circle, and dared calling it a shell, likewise revolving on itself.” Ibarra and Sor Juana are joined by shells. Alondra de la Parra is a successor in style and talent to both of them.

From Argentina came Imagenes, two of four seasons by Astor Piazolla and arranged by the orchestra’s Lev Zhurbin. The Argentine composer was selected because that country too is celebrating its bicentennial of its freedom this year. Although the impressions did not suggest Vivaldi, they certainly evoked fall and winter.

The program ended with a wild piece by Candelario Huizar and an encore which everyone joined in adding their claps.

Before each number de la Parra spoke to the audience, pointing out the special qualities of the composer. We heard strains of many pieces of Mexican music. The pre Columbian period gave music Indian dances. The Spanish influence is old and deep. Slaves who came from Africa in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries contributed too. European dances, particularly the waltz and polka came in the nineteenth century. The Cuban bolera was introduced late in the nineteenth century. Nationalist movements and the huge urban migration have also had their influence.

Much of the music performed sounded European, but as time went by, the look-back picked up a folk sound that has characterized music for the past hundred years. Composers have gone out into the woods and fields to gather beloved tunes which provide attractive cover for the bold innovations they want to deploy, like micropolyphony. The Mexicans claim to have discovered micropolyphony in 1922, but this may be like baseball, the Russians big find.

In New York, we are exposed daily to Mexican soul music performed by mariachi players on subway cars. These illegal immigrants can’t go for an audition with the Metropolitan Transit Authority because they would be deported. Mariachi groups originated at weddings in Jalesco in west-central Mexico and characteristically have a bass guitar. Subway riders get their daily fix, but it is neither as searching and nor as consequential as de la Parra’s.

Talking to Jenna Bush on The Today Show recently, de la Parra emphasized outreach to young kids in school, whose enthusiasm for classical music often starts when they recognize their own traditions in music being played. What better ambassador than the young Mexican woman who took the podium to conduct her young orchestra with such precision and passion.