The Dishwasher Dialogues, Paris, Two

Undocumented Getting a Real Job

By: Gregory Light and Rafael Mahdavi - May 26, 2025

In the 1970s the artists Gregory Light and Rafael Mahdavi were undocumented living under the radar in Paris. They were paid in cash with tips by a friendly bistro. It was just enough to scrape by. This chapter of Dishwasher Dialogues recounts efforts to get “real jobs," secure mail boxes and bank accounts. It took pluck and luck. The Dishwasher Dialogues is a successful book about their struggles to survive and pursue their creative work.

Greg: Somehow, we were living and getting by in Paris.

Rafael: Heating, canvas, clothes, food, paints, books. And the car? Parking was free. I took out the cheapest insurance, third party insurance. I kept it down to basics. A portable cassette player, maybe?

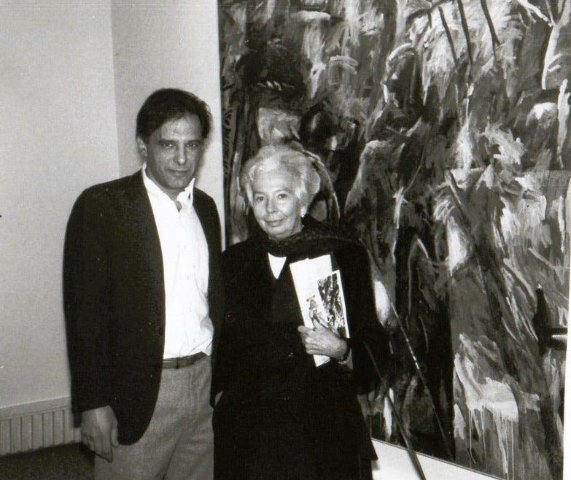

Greg: I didn’t know how you could afford your life. Running a car? I assumed you were rich—relatively speaking: a few hundred francs a month beyond my dreams. But then your painting began to make some money for you. You were exhibiting, solo shows at bona fide galleries on the Left Bank. And small red dots began to appear next to your paintings.

Rafael: I had a little money, but it wasn’t a state of mind. I went ahead with creative projects, such as your play. I say it wasn’t a state of mind because I, and you too, had been lucky, we were educated, and in good health, and the lack of money was a small obstacle. It was, more than anything, a physical inconvenience. I could afford museums, the Louvre was free one day a week, I forget which. We were confident our lives would lead somewhere, money wouldn’t always be a problem, although for me it did continue, but to a lesser degree. I was averaging two or three solo shows a year in Europe and America. I was making money. Ours was a confident generation.

Greg: Too confident sometimes. I think that began to change when the world didn’t turn out the way we all expected.

Rafael: I want to emphasize luck. I was very lucky. I have met over my life many painters who are better than I am in all ways, better technically, with a more fertile imagination, hard-working and self-disciplined, and they have had no luck, haven’t made it to square one.

Greg: Square one?

Rafael: I am convinced there is a universe of great paintings that hasn’t been ‘discovered’ by the critics and art historians and collectors. And probably never will.

Greg: Oh, that square one. Not Place de La Concorde. But vague recognition. And a living. Or the skeleton of a living.

Rafael: For some painters, bad luck grinds them into giving up, and I can’t blame them. It’s worse for sculptors. You do a few large pieces in stone and don’t sell them? You have to move out soon, the sculptures take up all the living and working space. I am sure that was before today’s conceptual sculpture, which presents no storage and transport issues and is very rarely any good. Sculptors had to find buyers or else they had to move or quit and moving implied already having money. Making sculptures you never sold drove you to quit doing it. Severe selection indeed.

Greg: Selection is always severe at the time. Less so in hindsight. I never experienced an existential state of poverty. A state of desperation and privation from which it was impossible to escape. We had a supportive community. That was lucky. And there was enough recognition and means of living that I was able to stay on square one for almost a decade. (Then my work and writing changed to a more life sustaining academic square one.) And, of course as you say, there was always the knowledge we could quit. Leave at any time. Get a ‘real’ job. It was always a topic of conversation. Many left, returned home.

Rafael: Sadly, I couldn’t go home. My father’s pension was barely sufficient. I couldn’t go home and live off my parents.

Greg: I eventually left Paris after four years. To carry on in London. Going home, meaning the place I came from, had to wait forty years. My parents had died by then.

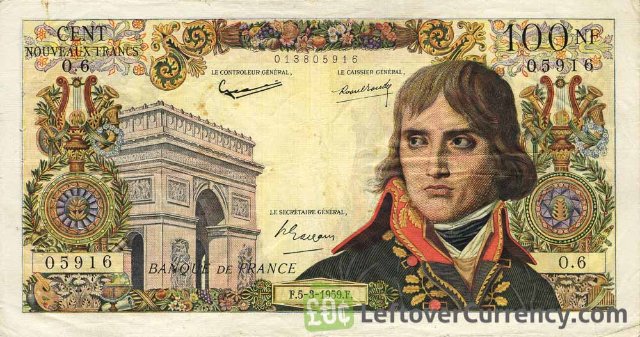

Rafael: Money, going home, was a constant source of worry. Leroy paid us in cash, which I kept on me most of the time. I did open a bank account in the end, for a silly reason: it made me feel more settled, rooted somehow. I needed roots. I had lived in Mexico, Spain, Austria, England, U.S., France. I know it’s ridiculous, but that’s what I needed. I had moved around so much that now I wanted to be settled. Look, see, I have a bank account, and I have my address. It’s on my checkbook. It was easy opening a checking account, much easier than it is now, and even though I had a tiny balance, the bank told me I could overdraw too. Made me feel rich, that did. I didn’t declare any tax information. Now I had a postal address, mailbox, and a bank account and even a check book. Wow! I was living in Paris. I wasn’t legal in the least, but that didn’t matter to me.

Greg: To begin with, cash was everything. We were solid members of the dark economy. Paid in cash and tips. Not that the tips were huge. I think, after we divided it up among the wait staff and the barman, it averaged 10F a piece a night. I remember the dishwasher was only paid 90 francs a night versus 100 francs for the waitresses and barman; no share in the tips for the kitchen staff which consisted of just me. When I finally transitioned to the bar, I lobbied hard for the dishwasher to be included. And he was. I had a small metal box under my bed which I would put money into to ensure the bills would be paid and projects save up for. A real bank account was not even on my horizon. But I do remember you getting an account and later a bank card. I remember the marvel of you going to what must have been one of the earliest ATMs in Paris to take out money. It looked like magic. With the help of your recommendation and my carte de séjour, which I was finally given, I also got a bank account. It felt so important and weighty that I did not give it up, or touch the money, until long after I left Paris. I finally closed it when I returned many years later with my wife. Still living on a tight budget, we were delighted to take the remaining 406F and feel exceedingly rich for a few days.

Rafael: And getting mail was free too. That was something amazing, and sending letters was affordable. You can imagine the excitement of opening my mailbox in the morning and when I got home from Chez Haynes late at night. There were three mail deliveries a day then, in the seventies. Would there be a letter from a friend, a girlfriend, a love letter or even a photo?

Greg: There was something nice about having a mailbox. Not that I remember many letters from friends, lovers, or devoted fans. Some responses from theatres or a venue about a performance or an idea. Mainly rejections, but sometimes an opportunity as well. The bulk were of the everyday kind, reminders from the landlord, electricity bills and notices from the city and the local community. There was never a perfumed card with an invitation to afternoon tea.

Greg: Although, I do remember a kind thank you card from your father for a book or something I had sent to him. On one of those literary cards with the sender’s name formally embossed on it. Very nice.

Rafael: I never knew this! That’s quite something. Amazing, really. My father rarely wrote letters, and the few he wrote to me in Vienna or later in college were illegible. Hopefully you deciphered his.

Greg: I did. It was short. A sentence or two. Much appreciated. As was the mailbox. Despite its lack of use, the mailbox with my name on it, sitting there among all the other very French sounding names, did confer an additional sort of legitimacy about my life in Paris. Eventually I had two mailboxes. The second was not mine at first. Tex, who had moved into the chambre de bonne next to mine, ‘owned’ it, until the beguiling song of Texas summoned him back home. I was loathed to surrender the room, especially the shower, so with your help, Laura and Sophia and I made it into a darkroom. They were photographers and we saw it as a tool to create and sell work. Rather than let the landlord know we were running a commercial business out of the room, we created yet another organization which was called “LE Word Image Services”. The complicated multi-language name was designed to provide a contraction which was the existing surname on the mailbox. We ran a little business out of there for six months or so before one or both left Paris for home. Almost as unfortunate as losing those wonderful friends, I also lost the use of the purpose-built shower stall. I could not afford to keep up the rent on that chambre de bonne as well as mine. So, it was back to square one. Back to the fold-down shower on my front door.

NEXT WEEK: BUKOWSKI, De BEAUVOIR et MOI