NY Theatre Workshop Continues the Saga

Mfonsio Udofia's Her Portmanteau

By: Susan Hall - May 27, 2017

Her Portmanteau

By Mfoniso Udofia

Directed by Ed Sylvanus Iskandar

New York Theatre Workshop

In association with The Playwrights Realm

New York, New York

May 26, 2017

Photo credit Joan Marcus courtesy of New York Theatre Workshop

At the New York Theatre Workshop, Her Portmanteau is a mash up between Nigerian and American, perhaps Amgerian.

Lewis Carroll used portmanteaus in his jabberwocky, mimsy and slithey among them. Celebrity lingo has Brangelina (now severed), Bennifer, and Billary.

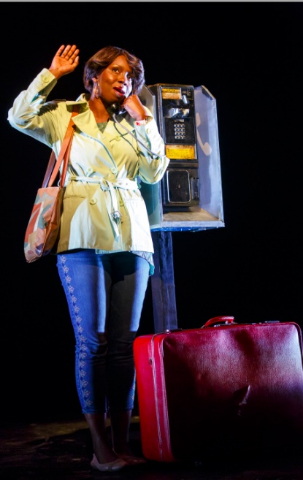

Portmanteau in this section of the Ekpeyoung saga is the red suitcase Iniabasi carries with her to America thirty years after she was born in Texas. It belonged to her mother, who sent her back to Nigeria with her father when she was only a few months old.

The mother went on to marry a seemingly stable religious man who's now gone nuts. Central to how the trio this portion of the saga will play out is the mother's second daughter, half sister to Iniabasi.

Why families are drawn back into each other is a curiosity of modern history. Today, even if you don't like your brothers and sisters, or your mother and father, you are still curious about your gene pool. Nobel prize winner James Watson thinks we inherit everything.

Iniabasi is now a single mother, as her mother was at her own birth. She is making different choices. Her mother sent her back to Nigeria with her personal portmanteau, red leather with a slash on one side. Now Iniabasi is returning to America, to her birth mother who will also receive in time Iniabasi's son, perhaps fathered by her mother's father. Incestuous family trees are not uncommon in Africa.

What one feels as the three women, a mother, and two half-sisters, reunite is the perfume of the tropics, the smells of thyme and curry and ehuru. There is a yearning for unity that years of separation have made difficult. These women want to come in from the cold.

Again Ed Sylvanus Iskandar's directing keeps the on-stage action moving and gives the actors ample opportunity to strut their stuff. Adepero Oduye seems appropriately stiff and numbed as she tries to negotiate her new home and meet these relatives who are strangers. Jenny Jules is an older mother Abasiama, thin, but perky, grasping at her confusion of feeling and trying to order it.

Chinasa Ogbuagu is step-sister, competent, caring and at her wits end trying to find something to please her step-sister. Like her father, she kneels and thrusts her hands to heaven from time-to-time.

The set is stationary, a small apartment in upper Manhattan. Two door frames bookend the stage. One is empty and leads to a bedroom. The other has a door. Again a massive frame filled with glass hovers over the set. In the end, as the trio warms and begin to accept each other, it bursts into a radiance of color made up of family photos.

The world is silent, except for talk, sometimes in English and also in Igbo. Abasiama recalls at one moment that the only laughter in her life came with Iniabasi's father. For the audience, ripples of laughter erupt amidst moments of pain and struggle. The drama may be about Nigerians, yet it is about all of us.